POVERTY, POTS AND GOLDEN PEANUTS

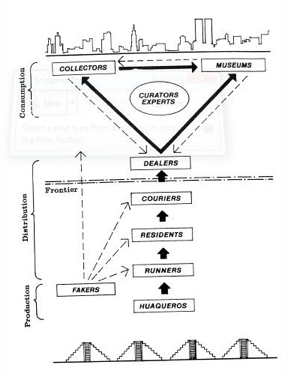

By Daniel RadthorneContributing WriterAbstract: The expansion of human population and the international trade in looted archaeological artifacts are destroying the world’s archaeological resources at an unprecedented rate, creating a complex problem which now affects literally hundreds of thousands of archeological sites and as many unique ancient cultures as can be established by academics. This essay will frame the problem through focusing on the North Coast of the Republic of Peru, especially the Moche Valley. Key to understanding this issue is a description of the two major threats facing archaeological resources in Peru and elsewhere; encroaching development (often through squatting) in response to globalization and the looting of archaeological artifacts to feed a black market, that spans the globe and is driven by wealthy countries in North America and Europe. These are put in perspective through discussion of the Moche Tombs at Sipan and a detailed examination of two specific sites in the Moche Valley._____It is no secret that we do not live in a perfect world. War, famine, disease and other maladies continue to indelibly stain or destroy the lives of hundreds across the planet; a fact our leaders, media outlets and enemies are eager to remind us of on a daily basis. The advent of modern technology has made it easier than ever to stay informed of the world’s many woes on a minute-by-minute, and increasingly, a second-by-second basis. With such a sophisticated system for keeping track of global problems, it seems especially unusual that mainstream society would miss one; especially one that threatens to destroy the very fabric of our history, and prevent us from ever truly understanding our common heritage as a species. I am speaking, somewhat dramatically, about the increasingly prevalent destruction of the World’s archaeological resources at the hands of development and the antiquities trade.This problem is a complex one, which can has spread around the world to affect literally hundreds of thousands of archeological sites and as many unique ancient cultures as can be established by academics (Renfrew 9-17, Brodie & Doole 1-4, Alva 91). The sheer scale of this issue makes accurately characterizing it in its entirety beyond the limited scope of this paper, and as such this essay will focus on one particular area; the North Coast of the Republic of Peru, especially the Moche Valley, and how the international trade in looted antiquities has caused irreparable damage to its cultural heritage. Key to understanding this issue is a description of the two major threats facing archaeological resources in Peru; encroaching development (often through squatting) and the looting and transfer of archaeological artifacts through a black market trade system that spans the globe and is largely driven by wealthy countries in North America an Europe. These are put into perspective through discussion of the richest Peruvian archaeological discovery in recent history, the Moche Tombs at Sipan, and the consequences of this discovery for the international antiquities, trade and Peruvian archaeology. Finally, we will conclude with an analysis of the present and future state of cultural resource management on the North Coast through detailed examination of two specific sites in the Moche Valley. What are the threats? SquattingDefinition and HistoryPrior to the 60’s and 70’s, Peru was ruled by an elite class of gentrified families, many of whom derived the majority of their wealth from ownership of vast tracts of land (such as the Auriches of Batan Grande). However, when the military regime of General Juan Velasco took power in 1968, the new government began a number of “land reform programs” intended to destroy the power of Peru’s landed aristocracy in favor of state-driven economic development. This was accomplished principally through the creation of a number of campesinos; land cooperatives among the farmers and laborers that had previously operated the land for the ruling families (Atwood 104). While this created an important shift in the character of Peruvian looting practices (to be discussed in the next section) it is perhaps more important for the legacy it created in Peruvian private property rights. Today, land ownership laws in Peru are complex, but generally legally favor squatting, as it is believed that this will encourage national economic expansion. If one is able to build a house on an area of unoccupied land, and inhabit it for at least 24 hours, it becomes very difficult to force the squatter off of it, and often the squatter is eventually granted legal title to the land (Billman, Interview).While this provides poor families a means of achieving shelter and increased economic assets, it can have dire consequences for cultural resource management. Modern squatters are often attracted to the same kinds of sites that attracted ancient peoples; areas easily accessible and close to resources like water. A general lack of public education about the value of archaeological resources means that modern shanty towns sometimes spring up on what appear to be well located, unoccupied stretches of land, but are actually ancient archaeological habitations or ceremonial sites (Silverman and Ruggles 15-16). While the INC (Instituto National de Cultura, the government agency tasked with protecting archaeological sites) has great legal authority to combat these practices, it lacks the budgetary resources or logistical support to enforce this nominal authority (insufficient funding and lack of alternatives mean that the INC relies on the police to enforce its rules, who are sometimes unconcerned with cultural resource preservation or corrupt). Also, the growth of squatting in recent years has created a cottage industry of “land brokers” who find tracks of “unoccupied” land (often containing archeological sites), clear and divide the land into lots, and sell them to impoverished families as places to squat, lending an air of legitimacy to the situation and further complicated the process of cultural resource protection. Without the assistance of another party (like a concerned archaeologist or sympathetic NGO) the INC is often powerless to prevent a site’s destruction, especially if there are forces with any degree of funding, influence, or persistence working against it (Billman Interview, Silverman and Ruggles 15-16).ExamplesThis was the case for the settlement of Las Lomas just above the growing beach town of Huanchaco, North of Trujillo. The heart of this squatter community is built atop a known archaeological site classified by the INC as a “Zona Intangible”, and should have been protected by law. However, the persistence of the local community, and the resources of the Communidad Campesina de Huanchaco, ensured that the INC would be unable to prevent the further development of the settlement. Even major Archeological sites are not safe from the encroachment of development. Chan Chan, the massive adobe compound that was once the seat of the Great Chimu Empire (built around 850 AD and occupied by as many as 30,000 people until the Chimu were conquered by the Incas in 1470) was once roughly twenty square kilometers, but today is closer to fourteen. In addition to threats from weather (notably occasional El Nino events) the INC has consistently defended Chan Chan from encroachment by local farmers and squatters. However, relatively open access to the site in the past and the impoverishment of adjacent communities has also resulted in the theft of adobe bricks from the city for use in building new communities, weakening the standing structures and causing collapse (Castellanos 107-110, Silverman and Ruggles 16). Increased development and stronger restrictions placed on looting have caused squatting to become the new greatest threat to rural archaeology on the North Coast, as will be discussed in greater length through the examples in section 3. That said, the history of cultural resource management, or even Peruvian archaeology in general, is intrinsically connected to (and marred by) what is still arguably its greatest challenge country-wide; the clandestine looting of archaeological sites to fuel the global antiquities trade.LootingDefinitionIn the words of renowned archaeologist Ricardo Elia, looting is “the deliberate, destructive and non-archaeological removal of objects from archaeological sites to supply the demand of collectors for antiquities” (Elia 86). This “removal” principally takes the form of illegal excavations, the defamation of a statue, mural or other freestanding work of art, or the theft of specific objects from standing archaeological structures. This increasingly widespread looting of archaeological sites can accurately be labeled a “catastrophe” (Renfrew 15) because of the principle way in which archaeological knowledge is gained; through the study of context. An item’s “context” can be the most informative contribution the item makes to our existing knowledge. Traditionally, “context” or provenience to some, describes the stratigraphic or merely physical position of an artifact within an archaeological site. By analyzing the stratigraphic layer an object is found in, or its place relative to other objects or features, archaeologists can sometimes determine the period to which the object dates and perhaps its intended significance for the society that crafted it. An object that has been looted is by definition out-of-context, and as such, much of the information potentially learned from it is lost (Billman interview, Renfrew15-16). However, as archaeological technologies advance, and new, more specific specialties develop, even these terms cannot fully encapsulate the nature of this destruction. As Neil Brodie argues in Illicit Antiquities: The Theft of Culture and the Extinction of Archaeology, “for a student of ancient textiles, the fragment preserved in copper salts on the surface of a corroded bronze blade might by the object, and the blade its context.” (Brodie & Tubb 9), and by extension, the cleaning of such a blade (as might happen in the course of preparation for sale in the antiquities trade) would result in the loss of that knowledge. Archaeological sites are thus better characterized as a “web of relationships,” all of which are destroyed when antiquities (the traditional “objects”) are looted and enter the private market (Brodie 9).HistoryIt can be calculated that there are approximately 200,000 archaeological sites in Peru, belonging to a number of distinct cultures across roughly 4,000 years, but it is almost certain that every one of them has been at least partially affected by looting. Looting in Peru has a long and destructive history. We know from written accounts that, during the Colonial Period, the Spanish treated temples, palaces, or any other obvious civic or ceremonial site likely to contain precious materials as sources of wealth for the Crown, and commissioned excavation “cartels” under “mining contracts” to obtain these materials by the most efficient means available. This resulted in massive damage to virtually all major archaeological sites known to the Spaniards, especially the Inca capital at Cuzco and the Huacas Del Luna and Sol (with the Spanish diverting the Moche river directly into the latter, washing away 2/3 of the original adobe structure) (Alva 89, Atwood 40, Billman Interview). There is a long-standing local tradition in Peru which revolves around the looting of archaeological sites during major holidays. Often this corresponds with the Christian Holy Week, during which time it is believed ancient pots are drawn closer to the surface and are easier to find. It is unknown how far back the underpinnings of this tradition go (possibly to before Christianity arrived with the Spaniards) but recreational looting has existed for long enough for its continuance to be a matter of familial pride in some places, where it also often continues to be done for sport (with the artifacts serving as trophies) (Rucabado-Yong interview, Alva 91).The actions of the Aurich family of Batan Grande, as well as the other landed Gentry in mid 20th century Peru, represented another step in the evolution of the modern looting phenomenon. Between 1940 and 1968 the Auriches fielded teams of agricultural workers already in their employ as an organized looting army, complete with bulldozers and other heavy equipment. The result has been characterized by Walter Alva as possibly “the most extensive pillage in the New World” with almost 100,000 looters pits dotting the area around Batan Grande. A single tomb sacked in 1965 contained 40kg of gold, and it can be estimated that 90 percent of all archaeological gold attributed to Peru held in Museum collections worldwide was ripped from the Earth at Batan Grande (Alva 90-91). When the land reforms took effect in the late 1960’s and early 70’s, the campesinos (who now collectively owned most of the Auriche’s land) likely continued to use heavy equipment to pillage sites (as they possessed the training and means to do so and there was no one to stop them), setting the stage for the explosion that came in the late 1980’s. The combination of improving technology and the gold-rush fever induced by the discovery of Sipan (discussed in the next section), caused a massive spike in the most prevalent variety of looting in modern Peru; pillage-for-profit by commercially motivated looters, often called Huaqueros (Brodie1).StructureEstimates of the annual value of the antiquities trade (generally part of the “art market”) range from $300 million to $6 billion, a spread which arguably better indicates the dispersed nature of the trade and general paucity of data available to official authorities than any real understanding of its magnitude. The essential structure of the looting trade has not change much in the last several decades, though it has expanded exponentially in scale and sometimes made use of improving technology. In Figure 1, Michael D. Coe shows the basic stages a looted antiquity goes through on its way to a Western collector or museum (generally their final stop), beginning with the Huaqueros (274). As Kimbra L. Smith describes in Looting and the Politics of Archaeological Knowledge in Northern Peru, “The word huaquero comes from huaca, a Quechua term meaning sacred, strange, or special; in modern coastal Peru, huaca usually refers to pre-Hispanic archaeological sites. A huaquero, then, is one whose work usually revolves around “huacas” (150). During my time in Peru this summer, my superiors generally applied the term to any commercial looters, whether they be professionals based in a city who travel around the countryside looking for Huacas to loot, or local people who loot sites adjacent to or within their settlements for extra cash. The former became much more common after the discovery of Sipan and the increased profitability of treating looting as a profession, whereas the latter is likely more an outgrowth of existing local tradition combined with the need/desire to supplement a meager income. It is estimated that 65 percent of the developing world’s population lives in rural areas and depend upon immediately available resources to meet their daily needs. Every few years the unfavorable effects of El Niño conditions can result in lost agricultural jobs, the main source of income on the North Coast, pushing people to subsist using whatever resources they can garner (including archaeological ones) (Brodie 4, Rucabado-Yong interview). In any case, Huaqueros, as the individuals who actually pull the antiquity from the ground, represent the first link in the antiquity trade chain. They frequently use picks, shovels and rock bars (Iron rods roughly four feet long intended for moving rocks but useful in locating subterranean chambers) to manually unearth artifacts. Once they’ve found pieces worthy of sale, they contact what Coe terms “Runners.”The “Runners” box in Figure 1 represents the various layers of middlemen and minor dealers and antiquity passes through before reaching a major dealer. Sometimes these are local dealers in small towns or mid-level organizers based in cities. In either case, the highest quality antiquities eventually filter through the hands of the “Runners” and into those of major art dealers, generally with connections to the foreign market (Coe terms these individuals “Residents”). These “Residents” are major players in the domestic art world and, in Peru, are almost always based in Lima. They have the cultural and monetary capital to access foreign markets, and the influence and discretionary funds to decrease the chances of customs interference. The late Raul Apesteguia, the famed collector, authenticator and sometime smuggler of Peruvian artifacts who was murdered in his Lima apartment in January 1996, and Fred Drew, the former American diplomat who was a primary figure in the Sipan case (discussed in the next section), are both prime examples.“Residents” sometimes export their products by way of “couriers;” while simply packing antiquities in a box alongside cheap tourist curios may be enough to pass customs in some countries, it is sometimes necessary (or at least safer) to use the assets of a third party. For single, relatively small pieces, airline employees or diplomatic staff can be bribed to carry the items into the desired “buyer” countries in their luggage. For larger shipments, more complex routes involving redirection through other countries are often necessary. Arguably Michael Kelly, through the use of his Santa Barbara connections and English birth, functioned as a courier for David Swetnam and Ben Johnson in importing the looted Sipan treasures to Los Angeles in 1987 (again, discussed in the next section) (Atwood 46, 84-85, 124). Once in the hands of “Dealers,” often auction houses like Christie’s, Sotheby’s, Bonham’s, and Phillip’s, the trade attempts to clothe itself in a mantle of respectability, facilitating the desire of their generally well-to-do patrons (both private individuals and institutions, such as museums) to display wealth through unique and beautiful objects and garner the associated social status and prestige. It is not uncommon for auction houses and high-end dealers to avoid looking too closely into the provenance of an item of mysterious or dubious origin and simply re-list the boilerplate origin story that accompanies it (“from a private European collection,” “found in a grandmother’s attic,” etc.) (Renfrew 36-38, Hawley 1). Here there is a certain degree of exchange between the various collectors, museums, and dealers, with occasional input from curators and authenticating experts. However, even the major private collectors often view the final destination of antiquities as a museum. Through collaboration with museum staff, many private collections are printed into glossy coffee table books and catalogs, which increase the resale valuation of the pieces and allow the collector to donate them to a museum for an inflated tax deduction (the awarding of tax deductions for the donation of possibly looted antiquities continues to be an especially hotly debated issue) (Renfrew 35).By continuously paying into this system, it is often argued that Collectors and wealthy museums are driving and exacerbating the illegal loot trade by creating generalized demand. While the debate is ongoing, the sheer volume of archaeological material on the market suggests that the vast majority of the antiquities circulating today are looted; some hypothesize as much as 90 percent (Elia 92). Of course this is simply the most common version of the illicit trade. Sometimes, a wealthy patron with the right connections can “order” a certain variety of antiquity (and have it provided via the “Huaquero”-“Runner”-“Resident” system) or order a specific artifact be “acquired” for them from a museum, storehouse or other secured holding area. However, none of these systems were nearly this sophisticated before the modern age of archaeological looting began outside a small town in Lambayeque in February 1987. 2. Sipan A) DiscoveryAround 10:30 p.m., Ernil Bernal, an unemployed truck mechanic, along with two of his brothers and several other men, were digging a boot-shaped hole into the side of Huaca Rajada, a large adobe structure generally associated with the Chimu culture (800 years or so after the Moche). Unlike the local looters of past decades, who made offerings to the spirits of the dead before digging and feared the spirits’ supernatural retribution if too much was taken from a huaca, the Bernal brothers cared only about muscling themselves onto the most promising archaeological sites and harvesting as much loot as possible before moving on (they had reportedly threatened Ricardo Zapata, the man living with his mother at the base of Huaca Rajada, at gun point if he did not allow them to dig there). At twenty-three feet down, Ernil found several gold beads in the ceiling of his tunnel and began to dig upwards, only to be covered in an avalanche of adobe and sand. When his fellow Huaqueros responded to his calls for help, they were stunned to find numerous metal objects mixed in with the material around him. The exact timeline after this point varies by individual recollection, but at some point in the next few days the men began digging into the top of the chamber that Ernil had entered from the bottom and, after going through a layer of 200 pottery jars and eighty or so copper artifacts (few of which survived) the men struck gold. To describe in detail all the golden Moche treasures discovered by the men would take pages, but the essential fact is that the artifacts represented some of the finest examples of Moche metallurgy yet seen, and the Bernal brothers and company pulled hundreds from the soil, including a number of peculiar gold and silver Peanuts (perfect replicas of their legume counterparts but several times larger, and unlike anything found before in Peru) (Kirkpatrick 16-20, Atwood 41-44).The Bernal’s contacted a man known as Pereda, a former police officer who lived in a villa in Trujillo and was known to small-time professional looters for only buying the highest quality items. In Coe’s terminology Pereda would be a “Runner”, with strong connections to “Residents”; soon enough, Pereda had those “Residents” coming to his home to see the objects for themselves. One was Fredrick Drew, a former American diplomat who had begun antiquities dealing full time in the 1970’s and had since developed an efficient system for smuggling pre-Columbian antiquities out of Peru (generally through airline couriers or over land to Bolivia and then by air to North America or Europe). A quiet, elderly man with crutches, his extensive network of looters and “Runners” ensured that most professional huaqueros had worked with him at some point, and made him the ideal person for obtaining foreign clients who could pay top dollar for the magnificent Sipan artifacts. Drew’s first rival for the loot was Enrico Poli, an Italian immigrant and former hotel manager who possesses a collection of Peruvian gold artifacts that is the envy of most every museum in the country. Unlike Drew, Poli never sells his pieces, preferring to keep them (in Peru, it is legal to “possess” looted antiquities as long as one “registers” them with the INC, which theoretically “owns” them; the system is a poor imitation of the one employed in France and is a source of much contention in the archaeological community).Drew and Poli reached the Sipan stash first, but were followed shortly thereafter by Raul Apesteguia, a favorite among Lima’s cultural elite who fancied himself a connoisseur. Apesteguia had a reputation as a master authenticator, and in the heated world of Peruvian antiquities, often served as an unofficial diplomat, welcoming both archaeologists (such as Walter Alva, with whom he was good friends) and dealers and collectors into his apartment to view his collection or discuss business. Apesteguia was primarily however, a dealer and market maker and, though some of his previous attempts at smuggling had led to unpleasant brushes with the law (he spent time in the infamous Lurigancho prison) he saw Sipan as a last great score before quitting the export business (Atwood 46-50).In 1987, Walter Alva was the 35-year-old director of the Bruning National Archaeological Museum, a small but well respected local museum on the North Coast that Alva had successfully reorganized and improved. Alva was known for a few published field reports and locally as a vocal opponent of looting, which he saw as destructive to both the archaeological record and indigenous Peruvian identity, but not as a central figure in the field. He might have finished his career in relative obscurity had a disagreement not broken out between the looters at Huaca Rajada, resulting in a gun battle and one huaquero tipping off the police. When Alva was beckoned to the police station from his bed just before midnight on Feb. 25, 1987, he was greeted at the police stations with a rice sack of 23 exquisite objects confiscated during a police raid on the Bernal home (undergone on the informant’s tip). When Alva arrived at Huaca Rajada the next morning, it was overrun with hundreds of villagers desperately searching for anything valuable. Most archaeologists assumed that the tomb was sacked and anything valuable would be long gone, but Alva’s intuition told him there was more to find and, within few weeks, Alva and a team of students and laborers were living under 24-hour armed guard on the Huaca, excavating what they could. Christopher Donnan, a well respected archaeologist at UCLA, was an early supporter of the project, and helped Alva to obtain initial grant money (and a camera). In the meantime, a second raid on the Bernal house on April 11, intended to find more of the stolen loot, resulted in the death of a fleeing Ernil Bernal (whose mind had by now severely deteriorated from consistent drug use) when a policeman’s bullet punctured his liver. The situation at Sipan was becoming more complicated, and while some artifacts the looters missed were still emerging, Alva knew he needed a truly new discovery to justify his tenacious efforts (Atwood 57-63).It came, in spades, on June 14. Working a few yards from the looters main shaft, Alva’s team discovered, and painstakingly excavated, a second tomb, filled with riches beyond imagination, and providing the best possible analog for what had been lost from the looted tomb. Counting the tomb discovered by the Bernals and their team, Alva eventually found and excavated three ruler’s tombs, as well as numerous priests and attendants, complete with bodies and grave goods. To Alva, identifying these men, these bodies, as the first recognizable, individual rulers discovered in Peru (in fact, tests would later indicate that these three rulers may even have been a ruling dynasty connected by blood) provided the Peruvian people an unprecedented connection to their past, and he insisted the bodies be treated with the same ceremony as a former head of state. As a side note, one of Alva’s most beautiful discoveries was a set of twenty over-sized gold and silver peanuts (just like the ones the Bernals had found) which, when formally excavated, were clearly beads in an exquisitely crafted necklace (see Figure 2). The necklace is today on prominent display in the Sipan museum fully restored, while the Bernal beads remain spread around the world in multiple private collections; a case in point if ever there was one of the importance of context and the exponential rewards of proper excavation (Atwood 64-70).Meanwhile, the artifacts unearthed by the Bernals and their crew continued to circulate on the world antiquities market. Fred Drew had succeeded in sending several shipments of gold artifacts to American dealer Ben Johnson (who sold to art world elites like Norton Simon and Armand Hammer from his home in Santa Monica) and his business partner David Swetnam, who ran a gallery in Santa Barbara. Using Michael Kelly, an English expatriate and art consultant desperate for cash, they smuggled in well over $1 million in gold artifacts via England as “personal effects” (Kelly was not aware of the true value of the shipment and felt betrayed enough to later inform on the dealers to the authorities). Some of these pieces ended up in the hands of John Borne, and aging collector who would later donate/loan several items to the New Mexico Palace of Governors Museum for a tax break (inciting a protracted repatriation battle with the Peruvian government) (Atwood 121). The largest gold object found at Sipan, a piece of ceremonial body armor known as a backflap, was so massive and ostentatious (at 1,300 grams and 68cm long by 50 cm wide) that it was first considered too-hot-to-handle and then passé by the Peruvian black market. It circulated between small-time dealers in Peru for almost a decade before a Puerto Rican businessman (Denis Garcia) smuggled it into the United States with the aid of Frank Iglesias, the then Consul General of Panama. Luckily the illicit transaction they planned to carry out at a rest stop on the New Jersey Turnpike turned out to be part of an undercover sting operation by FBI investigator Robert K. Wittman (Atwood 83-84, Wittman 74-92). Yet hundreds more pieces from Sipan likely remain under the radar, stashed in private collections, only to resurface as tax deductible donations in several decades.B) SignificanceThe Significance of Sipan cannot be overstated. Not only did it help spread the geographical focus of archaeology away from its roots in the Mediterranean and towards the Americas, but it changed the way archaeology and preservation was practiced in Peru as well. For better or worse, it forced many researchers to concentrate more on tombs and grandiose mausoleums which would be likely to yield rich artifacts and metalwork. This was both to protect the contents of such sites from falling into the hands of looters and because the public interest (and professional prestige) became focused squarely on the sites with the most potential star power. The high profile excavations of the Huaca del Luna and El Brujo complexes demonstrate this trend (Billman Interview, Atwood 119). Even more pronounced however, is the effect it has had on the rate of looting and theft. As discussed above, the decades since Sipan have seen an unprecedented spike in looting; it is estimated that more archaeological sites have been pillaged in the last few decades of the twentieth century than in the preceding four centuries combined (Alva 91). While market tastes have shifted away from Moche pots and metalwork found mostly in the North and towards fine textiles from the Nazca and Inca in the South, the overall scale of looting has not diminished. Some estimate that the number of professional looters active on any given day could be as high as 15,000, and perhaps many more, with additional subsistence looting by local communities (Atwood 240). While changing taste and a drying up of supply have likely contributed to the shift of antiquities looting to the Peruvian south, it is likely also due, at least in part, to increased protection efforts by archaeologists, NGOs, and local communities.3. Two Cases from the Present; a Glimpse of the Future? 2) Bello HorizonteBello Horizonte is a large community (by the standards of rural Peru) with 2,500 people located in the middle Moche Valley. For several years MOCHE inc. (Mobilizing Opportunities for Community Heritage Empowerment, an NGO run by archaeologist Brain Billman of UNC Chapel Hill) has been in negotiations with community leaders to build a health clinic in the town, in exchange for the villagers’ cooperation in creating and maintaining a large archaeological preserve in the foothills and mountains the town backs onto (see Figure 3). Unfortunately, progress has been impeded by a number of factors which are becoming increasingly common problems for preservation efforts on the North Coast. As recently as last summer (2009) the southeastern boundary of the proposed reserve was a considerable distance from any houses or development, save a few small shacks (see Figure 4). However, during the early summer, in preparation for the upcoming Fall elections for local and district officials, a bulldozer “mysteriously” appeared one morning and created a road from the center of town up to the proposed reserve area. Afterwards an individual arrived who made a point of claiming they he had “absolutely no connection” to the incumbent candidate, but just happened to know that those who built houses and squatted on this “newly accessible land” would be given legal title to it their new lot if they voted to keep the incumbent in office. This kind of vote-buying is not uncommon in rural Peru, but in this case it is especially problematic, as it threatens the preservation of archaeological heritage. By just a few months later there were already several rows of houses built right up to the reserve boundary and, in some places, over archaeological sites (see Figure 5). The INC wanted to prosecute the individuals squatting on what used to be archaeological sites, but MOCHE inc. brokered a deal whereby the villagers agreed not to expand any farther into the reserve in exchange for the INC not seeking charges against those living atop former archaeological sites. So far there has been no further encroachment (Billman interview).On the other side of the ridge, which almost bisects the town, lies an area of several small archaeological sites, including a pre-Moche adobe mound and several Moche and Chimu habitations. This area is essentially undocumented and forms the fragile edge of the proposed reserve’s southwest boundary. As is the case with most archaeological sites in the middle Moche Valley, development has continued right up to the archaeological structures. I visited this area twice during my time in Peru, both times with Professor Billman and Julio Rucabado-Young (one of Professor Billman’s former graduate students). The first time was late July, and I was surprised to find the site largely cleared & marked into lots with chalk, with deep holes dug into the pre-Moche mound (undoubtedly to obtain the finely processed sand used to construct the rows of bricks assembled nearby in preparation for the new squatters’ dwellings) (see Figure 6). When we began gathering the tools and material laying about the site to drop them off at the police station, we were confronted by several villagers who had been involved in making the adobes. A long discussion ensued, in which the legality of building in the area was argued extensively (see Figure 7). We later discovered that “land brokers” had divided the lots and sold the “rights” to squat to several families, and that one of the “brokers” was the brother of the town’s deputy mayor (which had contributed to the confusion over just what was officially sanctioned). We left from this first visit when the villagers promised to stop expanding onto the land, but returned a second time to find the problem had gotten worse, with more pits dug, adobe’s made, and lots laid out. However, after more discussions with the town’s leaders, and a public health fair in the town put on by the NGO Nourish International, the villagers agreed to come fill in the holes, sweep away the chalk lines, and otherwise restore the site (Billman interview).2) Cruz BlancaCruz Blanca is the name given to an ancient hilltop settlement North of Menacucho, at the upper end of the middle Moche Valley. The architecture and pottery sherds scattered around the site suggest that the Moche, Chimu, and perhaps even some highlanders made their home there in the past. The area is surrounded by a number of ancient farming terraces built from local jagged stones. Recently however, many of these ancient farm works have been completely cleared to make way for brand new farming terraces (see Figure 8). Thankfully only a quarter of the site has been effected, but the juxtaposition of new and old (see Figure 9) is startling, and is a common them in agricultural areas on the North Coast. Across the quebrada the recent agricultural expansion has been even more pronounced, and is rapidly advancing over a small hill towards a Moche cemetery (See Figure 10). MOCHE inc. is currently speaking to the INC about possible actions to be taken, but the local villagers are not especially friendly to outsiders and progress is slow.Both of these examples have elements of increasingly common problems encountered by those seeking cultural resource preservation on the North Coast. While looting for antiquities still occurs, looting of building materials, and the clearing of land for squatting, agriculture, or to harvest mineral resources are all becoming much more prominent. The situation is further complicated by illegal “land brokers,” questionably moral politicians, and others who profit from exploiting cultural heritage. However, the common thread throughout all three cases discussed above is the importance of community involvement in any successful plan to protect archaeological sites. Brian Billman’s philosophy in founding MOCHE inc. was that “If a community can destroy a site, they can also protect it.” (Billman Interview). Indeed in Cuidad de Dios, the small town in the middle Moche Valley in which Professor Billman has worked for over 12 years, the archaeological resources adjacent to the community remain intact. A similar mindset is the basis for Walter Alva’s grupo de protection arqueologica, in which small bands composed of local villagers patrol the sites adjacent to their settlement in shifts, calling the police if they see any illegal looting or squatting. (Atwood 230).Archaeologists were lucky to reach Sipan before the fullest possible destruction could occur. Without the formal excavations at Sipan we would have a very different interpretation of Moche culture and ceremony and, perhaps even more tellingly, would be unable to correctly identify and understand many of the looted Sipan objects currently held in museums or circulating on the market (such as the peanut beads). This is arguably the case with La Mina, another major Moche ceremonial site likely contemporary with Sipan that was looted completely before archaeologists could study it. Today beautiful Sipan-esque pieces continue to travel the world through the art market, many likely from La Mina, but because of their lack of provenance, we will never truly understand them, or the ancient culture that created them. However, the minute we despair that looting and archaeological destruction can ever be stopped, we condemn out heritage to the looters pick and the auction block. There are several successful examples of repatriation of lost cultural antiquities (such as the Sipan backflap) all over the world, and more and more countries are signing the 1970 UNESCO Convention on the Means of Prohibiting and Preventing the Illicit Import, Export, and Transfer of Ownership of Cultural Property (historically the most influential international agreement aimed at stemming the illegal trade in looted antiquities). While there can be no doubt that we are in a state of emergency and that swift, decisive actions are required for the common educational future of mankind, we need not strike in the dark, as these actions should now appear straightforward and achievable. They include increasing regulation and openness of the antiquities market and helping combat global poverty to reduce the incentive to loot (and once the demand and supply side ebb, there will be no need for middlemen). So while the loss of global heritage will likely never receive as much mainstream media air time as war, famine, and chaos, it is still extraordinarily important, and equally solvable through increased global cooperation.Appendix:Figure 1: The graph below depicts the movement of cultural property after it has been illegally excavated.