BRINGING AFGHANISTAN HOME: AN ANALYSIS OF THE USSR'S INVOLVEMENT IN AFGHANISTAN AND ITS EFFECTS ON SOVIET POPULATIONS AND DOMESTIC POLICY

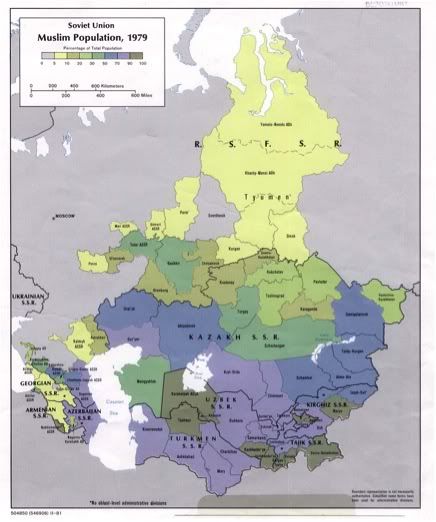

By Satenik HarutyunyanContributing WriterAbstract: The impact of Soviet involvement in the Afghan Civil War on domestic policy changes within the Soviet Union is a frequently debated topic. Scholars have also presented varying viewpoints regarding how the USSR’s role in Afghanistan affected domestic populations. There is however, limited insight concerning how both of these elements were related and the ways in which they helped shape the political environment of the Soviet Union before its collapse. Scholars attributing the changes within the Soviet Union during the late 1980’s to economic turmoil, overlook how foreign policy initiatives and the repercussions of invading Afghanistan added an important sociopolitical element, which influenced domestic policy.IntroductionSince the end of their potent wartime alliance during World War II, the Soviet Union and the United States were engaged in a perpetually fluctuating and tense conflict to assert global hegemony. Each fought relentlessly – without a direct declaration of war against the other – to emerge as the sole superpower in the global community. Regardless of whether the Cold War was a conflict of ideology, spheres of influence, or expansionism, both superpowers were consistently forming foreign policy with the aim to obstruct the rival’s goals. When the US invaded Vietnam under the pretense of saving an unstable nation from the evils of communism, the Soviet Union did not hesitate to provide arms and financial support to the Viet Cong opposition, ultimately playing a fundamental role in the embarrassing American failure. A mere decade later however, it was the US who provided continual funds and arms to the resistance movement against a Soviet invasion – this time the battleground was communist Afghanistan. The invasion of Afghanistan, dubbed the Soviet Union’s “Vietnam” by many, was a decade long struggle, which resulted in devastating military defeat and little political progress for the Soviet empire. The repercussions of the Soviet involvement however, were not only evident in Afghanistan; they also manifested themselves domestically, in the sociopolitical realm within the Soviet Union. The purpose of this paper is to explore these important domestic effects. This following research investigates the extent to which the Soviet Union's involvement in Afghanistan altered public sentiments and affected domestic populations, exploring how these social changes influenced political reform during the 1980’s.Existing Explanations: Why the Political and Social Environment of the Soviet Union ChangedThere are scholars who suggest that the inadequacies inherent in the Communist system caused an urgent need for reform within the Soviet Union during the 1980’s. They find that systematic structures such as central planning and a hierarchical bureaucracy were inefficiently executed, leading to a perpetually growing economic gap between the Soviet Union and the West, its ideological rival.[1] Some scholars also align these systematic problems with economic decline. They assert that the extensive, even radical, changes that manifested in the Soviet Union during the Gorbachev era must be attributed to the profound economic decline in the Soviet Union. Due to economic regression and turmoil, a new domestic framework was established, which in turn necessitated a decrease of foreign involvements and an overall reduction of resources allocated to defense initiatives.[2] Although these findings are compelling, they overlook a number of important sociopolitical phenomena occurring within the borders of the Soviet Union during the late 1980’s. As a result, such scholars generally ignore the impact of these phenomena on the altered political and social environment shortly before the Soviet Union’s unexpected collapse.HypothesisAfter reviewing existing research in political science literature, I aim to conduct an analysis combining domestic policy changes within the Soviet Union with the specific effect involvement in Afghanistan had on domestic populations. This deviates from conventional theories, asserting that the repercussions of the Soviet Union’s role in Afghanistan added a profound sociopolitical element previously missing in Soviet populations. I argue that involvement in Afghanistan played a contributing role in dictating domestic political reform during the second half of the 1980’s. My research will show that during this time period, partially as a result of the Soviet Union’s involvement in Afghanistan, public opinion and sentiment became important factors for Soviet political leaders. In order to confirm this hypothesis, I will analyze the role of the Soviet media as it relates to Glasnost, the role of Afghanistan War veterans in sociopolitical progress, the discrediting of the Soviet military as it pertains to domestic policy changes, as well as the alienation of minority populations within the Soviet Union. This research will span the time period of the Soviet involvement in the Afghan Civil War, focusing on the Gorbachev era to the final withdrawal of Soviet troops in 1989.Background: The Soviet Invasion and Occupation of AfghanistanIn order to illustrate the premise of the hypothesis outlined above, it is essential to understand the historical context of the Soviet Union’s role in Afghanistan. The Red Army invaded Afghanistan in December of 1979. At the time, the Soviet Union claimed the invasion was a response to request for aid from the newly established People’s Democratic Republic of Afghanistan, which was attempting to legitimize itself in an ideologically, socially, and politically divided Afghanistan. Ultimately, the precipitating event that had led to the establishment of Communist Afghanistan (and eventually the Soviet invasion), was the overthrow of former King Zahir Shah in 1973.[3] The Communist government established by the People’s Democratic Party of Afghanistan attempted to wholly and rapidly establish a socialist system within Afghanistan. This strategy, however, did not succeed in creating political stability, instead, it gave birth to the now notorious insurgency known as the Mujahedeen (predecessors of the Taliban). Throughout the conflict, the Mujahedeen received seemingly endless supply of weaponry and financial support from Western superpowers such as the US. The Afghanistan war ultimately marked the end of Détente and reignited the Cold War.[4] The Soviet invasion of Afghanistan gravely underestimated the military, economic, and social repercussions of the war. Occupation of Afghanistan lasted a decade without successfully stifling the insurgency. The following segments illustrate the domestic impacts of the Afghanistan War on the Soviet Union.The Role of the Media and Gorbachev’s GlasnostMikhail Gorbachev, the last General Secretary of the Communist Party, shocked the international community in the second half of the 1980’s when he initiated a series of radical domestic reforms designed to redefine the relationship between the Communist government and its populations. Engineered in 1985 and introduced officially in 1988, one such policy was Glasnost, which directly translates to “publicity” or “openness”.[5] The policy was designed to establish a more transparent image of the Communist government and help alleviate deep-seated feelings of government repression among the Soviet population. Some scholars believe that Glasnost laid the foundation and served as the primary catalyst for the rise of media that openly criticized the tangible shortcomings of the Soviet regime.[6] My research builds upon this to assert that there was a mutual relationship between Glasnost and the surfacing of relatively free press in the USSR. Furthermore, media coverage of the Soviet Union’s involvement in Afghanistan was an important, even axiomatic, counterpart of the departure from Communist Party lines. In this way, the Afghanistan war provided a gateway through which the media forces released by Glasnost could mobilize.From the initial invasion of Afghanistan in 1979 to the final withdrawal of troops from the war torn nation in 1989, the Soviet press’ portrayal of the Soviet intervention in the country evolved to develop an identity that was more independent of the Communist Party than ever before. At the outset, Soviet media sources functioned essentially as proxy messengers of the government, consistently reporting the strength of the Afghan Communist government and the nobility of the Soviet cause. One year after the invasion, the Krasnaya Zvezda (Red Star), a mainstream Soviet news source, concluded, “the indestructible unity of the party, government, people, army and security forces aimed at insuring Afghanistan’s territorial integrity, national independence and security…are bringing our victory closer than ever.”[7] Here, it appears as though the Soviet mission in Afghanistan was unfolding without obstacles, exactly as planned.Additionally, the media continuously upheld that the Afghanistan war was being fought by the Afghan armed forces. In these reports, the Soviet army was fulfilling its international duty and merely acting as a support system.[8] In an interview with expert Mark Galeotti, a Soviet captain by the name of Aleksandr Lukyanets recounts the following experience from 1983: “I remember I came back from a battle one day. It was a hard battle, with much bloodshed. That evening, I read the newspaper reporting how we and the Afghans planted trees together as happy friends. There was not a single word about the war. I felt deeply offended.”[9] Actual situations such as the one described in this anecdote were rare – yet in fact they were the norm portrayed in the media. Until about 1984, the Soviet press was careful to understate any Soviet military action, especially when it came to direct combat duty.[10]As time and subsequent reporting would show however, claims of a swift Soviet victory and limited Soviet involvements were gross miscalculations and fabrications that did not accurately depict the Afghanistan war. But by the second half of the 1980’s, levels of uniformity among Soviet media sources concerning the Afghan Civil War began to dwindle, paving the way for an array of reports with differing viewpoints. Importantly, press coverage showing enthusiastic support for the Soviet mission in Afghanistan was still being published and did not disappear altogether in the second half of the decade. The key point worth extracting here is that the growing incongruence among Soviet press regarding Afghanistan serves as a distinct example of the evolution of the media, and also in effect, of Soviet society. The shift in media portrayal started in 1985, when combat footage from Afghanistan began to air on Soviet television networks.[11] Additionally, the most well known Soviet newspaper, Pravda (Truth) concluded that the war in Afghanistan was not a matter of defending international socialism. Instead, the newspaper suggested a less glorified strategic reasoning, asserting that the invasion was merely a preventative undertaking to defend the USSR’s southern border.[12]Six years after the invasion, growing popular disdain for the war and the emergence of critical media coverage were making it increasingly difficult for the government and the military to mask the extent of the Soviet involvement.[13] By 1987, public input was already seen as a substantive source of information for mainstream media. An example of this was apparent in the summer of 1987, when Ogenek’s (Little Fire) war correspondent, Artem Borovik, published a three article series depicting the misery, bitterness, and wartime fatigue in the Soviet army.[14] The series was inspired entirely by letters from the public – presumably returned veterans, who will be discussed in greater detail in a separate segment of this paper. Additionally, newspapers such as Izvestya (Knowledge) began to reflect popular sentiments by establishing columns designated for public opinion polls on political issues like Afghanistan. Pravda (Truth) also began to incorporate a permanent column dedicated specifically to publishing commentaries and speeches by Western political figures.[15]Furthermore, it was at this time that the Soviet media began to publish reports of corruption and human rights violations within the Soviet army. Although a later segment of this paper will more extensively discuss the discrediting of the Soviet military, which steadily took place throughout the involvement in Afghanistan, such reports are mentioned now particularly to underline the media’s role in speaking out against an esteemed Soviet institution. Similar to the US struggle in Vietnam, the Soviet army experienced difficulties connected to widespread drug use amongst its troops during the war. Furthermore, accusations of corruption began to surface as reports of soldiers trading war equipment with the Mujahedeen in return for drugs, foods, and electronic goods made their way into mainstream Soviet media.[16] The army was also accused of heightened cruelty against civilian populations, stemming from a blurred understanding of who the Afghan enemy really was. As Galeotti argues, “there was a lack of distinction between civilian and non-civilian, hard and soft targets, legitimate and illegitimate.”[16] In terms of the military’s role in Afghanistan, the press helped to open a “Pandora’s Box on the intervention itself,”[18] as Sheik titles the phenomenon. Ogenek’s (Little Fire) Borovik pointed out this irony when he mentioned that the Soviet press could not determine who the Mujahadeen was in its reporting, thus having to rely instead on the term “the armed opposition.”[19] In this way, the press helped to articulate the vagueness surrounding the Afghanistan conflict to the rest of Soviet society. Without the war in Afghanistan, the press would not have had that opportunity to explore such unconventional reporting.The developments discussed above were certainly remarkable, if not ground breaking, due to the Soviet Union’s longstanding identity as a repressed society where freedom of speech was a far off notion. Additionally, these sociopolitical changes manifested themselves as a response to the Soviet Union’s ongoing and unsuccessful presence in Afghanistan. Thus, as this investigation of Soviet media has shown, the USSR’s foreign policy initiatives in Afghanistan influenced the drastic changes in the relationship between the Soviet government and its populations as well as in Soviet domestic policy initiatives.In a now world famous statement from 1986, Gorbachev described Afghanistan as a “bleeding wound.”[20] In many ways, when Gorbachev willingly and openly admitted policy failures, he was both reacting to signs of discontent as well as encouraging the media (and other public sources) to continue on along their new path of critique and analysis. In doing so, Gorbachev aimed to incorporate certain levels of popular discontent as a natural counterpart of political systems rather than an outlandish display of “rebellion” needing to be stifled. Without the legal privileges Glasnost allowed, the Soviet media’s emboldened autonomy would not have materialized nearly as extensively as it did during the second half of the 1980’s. However, it is also critical to consider the fact that Gorbachev and his administration felt an urgency to cultivate policies such as Glasnost in order to moderate the impact of growing public display of political criticism – as exemplified by the beginning of the media’s daring coverage of the Soviet Union’s failures in Afghanistan in 1985.The Role of the “Afghans” and Sociopolitical ProgressIn analyzing how the decade long Soviet involvement in Afghanistan dictated sociopolitical developments in the Soviet Union, it is fundamental to dissect the role of the men (and women) who served in this war – commonly nicknamed the “Afghans”. This segment of analysis demonstrates how Afghanistan war veterans actively participated in the restructuring of Soviet society through political activism unrelated to party politics. First, it is important to establish that not all “Afghans” contributed to this phenomenon. As a matter of fact, in a poll for Pravda, only about twelve percent of veterans cited politics as their primary concern.[21] That being said, activism of the “Afghans” rested not in the number of those who chose to get involved, but in the potency of their actions. There was also a relative lack of uniformity in veteran mindset regarding what exact societal and political changes should be implemented, resulting in a wide range of societal activism that the “Afghans” contributed to.According to the 1985 US News and World Report, there were already close to one million Soviet veterans who had returned from Afghanistan.[22] Official Soviet reports from the same year, however, released much smaller numbers closer to 308,000 troops.[23] Even among various Soviet sources, it is difficult to find consistency in the numbers of troops deployed. The large delta between US figures and official Soviet figures however, is not surprising considering their respective interests. For the US, exaggerating Soviet deployment numbers would impress and shock its public, helping to portray the Soviet Union’s role in Afghanistan as a vast and expansionist conquest. Accordingly, the Soviet government was careful to downplay their role in Afghanistan so as to avoid domestic scandal.[24] By the time the war was over however, the Soviet Union’s Committee for Soldier International Affairs released numbers that were closer to the actual Afghanistan deployment figure – 730,000 total troops.[25]For the veterans who took to political activism, there was a common mindset concerning two basic core issues. As expected, these similarities came into being largely as a direct result of their shared experience in the Afghanistan war. First, the veterans were concerned with morality in politics – specifically the politics of guilt and blame. Second, the veterans focused on the concept of representation and the idea of establishing elected entities to address their concerns.[26] But in order to achieve social progress toward these ambitions, the politically motivated veterans needed coordination through a legitimate method. In many ways, the city of Leningrad (present day Saint Petersburg) became the birthplace of grass-roots organization for the “Afghans” because the organizations stemming from this city focused on the “coalescence of local groups” within large cities and even broader regions.[27] These organizations provided veterans who shared a mindset regarding societal change a forum through which they could organize and eventually mobilize.One such organization, the Leningrad Association of Veterans of the War in Afghanistan (LAVVA), was formed in 1989 and acted as a unifying common ground for groups to come together. The main purpose of the organization was to harbor cooperation between local veterans’ groups, establish a common self-help program, and provide legal and social protection for the veterans of the war. The organization though broad in its nature, worked in close accordance with specified local groups such as the Union of Mothers of the Dead and the Invalids’ Union.[28] The purpose of the broader organization was to cater to goals and ambitions commonly found among such distinct groups. The presence of such displays of cooperation was evidence of a developing political network stemming from grass roots mobilization. This kind of political organization was certainly not commonplace in the Soviet Union prior to the Afghanistan war.Furthermore, as a result there was a rise in consensus within the “Afghan” coalition for the need of a national level body to articulate its views.[29] Here, it is clear the politically motivated veterans were seeking social progress and representation for the entirety of the veteran population. Consequently, two large-scale organizations were formed in order to represent the unity of the “Afghans” and their needs on a national level. These organizations were the Union of Veterans of Afghanistan (SVA) and the All Union Association of Reserve Soldiers’ Councils, Soldier-Internationalists and Military – Patriotic Unions (the Association). The SVA, which ran on a budget of 7,000,000 rubles (980,000 USD) and had official membership exceeding an impressive 300,000 people, adamantly focused on providing material help to veterans and their families. Thus it was “an organization devoted to the redistribution rather than the creation and acquisition of resources,” as Galeotti explains.[30] On the other hand, the Association, an organization comprised of a central body with four elements, included Dolg (Duty) and the Economic-Production Commission. The purpose of the former was to help invalid veterans while the latter focused on economic education and entrepreneurship.[31]After recognizing the missions of these organizations and the method by which they achieved their goals, it is essential to note that such organizations did not hold ties to the Communist party. As a matter of fact, they helped mark the beginnings of non-party aligned politics. This was a new trend in Soviet society, considering that the Communist Party had traditionally penetrated all facets of political and social life.[32] Because the Soviet leadership was adamant in concealing the true extent of involvement in the war, it also to a certain extent had to ignore the concerns and presence of the “Afghans”.[33] Without a stable flow of material or psychological support from the government, it is only logical that politically motivated veterans deviated from the government’s mission and established alternate ways to make their concerns known. Thus the Afghanistan war, and the discontent it brought to the veterans who served in it, planted the seeds of a political movement independent of the Communist Party and its ideals.The veterans of Afghanistan continued to become more influential in the political realm as they began participating in the Soviet bureaucracy and even holding public offices. These occurrences mainly began to take place in the latter half of 1989, which narrowly surpasses the timeframe addressed in this paper. Although I avoid delving deeply into that chapter of “Afghan” political activism, I do wish to point out a salient example of how this participation helped the “Afghans” directly impact Soviet political society. By the beginning of 1990, the Soviet government had instated a committee called the Supreme Soviet Committee for Soldier-Internationalists’ Affairs in efforts to respond to the needs of the “Afghans”. The Committee proved to be effective and within just three months of its inception, it successfully fought for a 50 percent tax discount for veterans. The Committee also ensured that all veteran organizations be exempt from government taxes.[34] In this way, the “Afghans” in the swiftly changing Soviet government helped to advance the goals of politically motivated “Afghan” organizations.From local specific organizations to national level groups to government involvement, the Afghanistan War veterans mobilized to initiate change in the way they were treated by the Soviet government and the place they held in society. Therefore, the conclusion can be drawn that political activism of the “Afghans” did result in material progress.The Social and Domestic Context of Discrediting of the Soviet MilitaryThe Soviet Union’s military failure in Afghanistan is an important factor to consider when analyzing the ultimate domestic sociopolitical impact of the Afghanistan war on the USSR. In asserting this, it must be recognized that on the surface the link between these two elements may seem abstract. Therefore, in order to fully apprehend how the military failure in Afghanistan contributed to changing domestic populations and societies, it is essential to understand how Soviet leadership’s and popular perceptions of the military began to shift throughout the decade long involvement in Afghanistan.First, it is important to establish what role the Soviet military played in society prior to the Afghanistan invasion. In many ways, the Soviet military was a pillar of Soviet society. After its endeavors during the Second World War, the Soviet military became a pinnacle of Soviet identity and its prestige was universally recognized throughout its populations. Reuveny and Prakash go so far as to depict the Soviet military as a “microcosm of the Soviet society,” because it harbored soldiers from many nationalities, with a focus on defending the ideological missions of the Soviet Union.[35] In this way, the army was a binding force of otherwise distinct Soviet societies not only due to its sanctified position in Soviet society, but also because of neglected ethnic differences.With the Soviet military’s traditional purpose in society established, it is then important to discuss how that identity changed as well as how Soviet military prestige diminished as a result of the Afghanistan war - thus altering this staple pillar of Soviet society. When the Soviet Union invaded Afghanistan, it grossly miscalculated the strength of their Mujahedeen enemy. Initially, Soviet strategists anticipated brief involvement in the civil war, hasty victory, and a prompt withdrawal.[36] Consequently, the USSR’s outright inability to defeat the insurgency came largely as a surprise, and efforts developed into a ten year-long struggle to no avail. Although the Soviet Union’s military failure against the Mujahedeen is a fascinating and complex topic, for the purpose of remaining focused on domestic and sociopolitical impacts, I avoid delving deeply into the specific (and important) hindrances to the Soviet goal such as US and Pakistani involvement, constant reorganization of the enemy, and the nature of mountain warfare in Afghanistan.By the mid 1980’s and particularly during Gorbachev’s era, there emerged a drastic and pivotal divide between the Soviet military and the Soviet government leadership. This concept was relatively foreign to the Soviet Union, especially because those two entities were traditionally interdependent when it came to their main ideological purpose: to support communism. As mentioned earlier however, the severe shortcomings of the Soviet Union in the Afghanistan conflict could no longer be denied.[37] As a result, the Communist leadership acted strategically in distinguishing itself from the Soviet military. This explains why the leadership adamantly assumed the position of publicly scorning the military and its incompetency in Afghanistan.Eduard Shevardnadze, the First Secretary of the Georgian Communist Party and the Soviet Foreign Minister at the time, released numerous statements articulating how USSR leadership was not responsible for the failures in Afghanistan. In 1986, Shevardnadze shared with Pravda the leadership’s mentality as it pertained to Afghanistan; he specified the following for the record: “Not having chosen this legacy for ourselves [but] accepting it for what it is, we are also obliged to take decisions as to how to deal with it from here on.”[38] Here Shevardnadze is directly implying that the leadership in power in 1986 was not responsible for the decision to invade Afghanistan, nor was it to blame for the lack of military success following the invasion.The blame-shifting that originated during the Afghanistan war – and the consequent Soviet military’s discrediting – created a new facet of Soviet society, one in which the two most important pillars of defending socialism were at ideological and practical odds with one another. This sort of public disagreement between auxiliary Soviet institutions, which was particularly highlighted thanks to the media exposure explained earlier, was indeed a previously unknown phenomenon for Soviet society. In his analysis of the Soviet military, Taylor points out, “the military, accustomed to a sacrosanct position in Soviet society, came under intense criticism in the liberal media on topics such as conditions in the armed forces and the size of the “military-industrial complex.”[39] Taylor’s point is salient as it deliberately underlines how the structure and integrity of the Soviet army was being blatantly questioned through public forums.Not only was the diminishing prowess of the military an issue on the social level, it even transcended to the realm of domestic policy during Gorbachev’s massive campaign to redesign the internal structure the USSR. Because it was in the Soviet Union’s best economic interests to reconsider foreign spending, the outcome of Afghanistan became of essence to domestic Soviet policy-making procedures. The Gorbachev coalition’s reform initiatives such as Perestroika (Restructuring), made domestic economic interests the focal determinant of foreign policy measures.[40] As a result, foreign expenditures needed to maintain Afghanistan were compromised, further placing the military at blatant odds with Soviet leadership motives. As Reveuny and Prakash suggest, “since a major focus of Perestroika and Glasnost was the demilitarization of Soviet society, the war emerged as a rallying point against the military.”[41] This statement synthesizes the distinct points addressed in this section and helps to socio-politically contextualize domestic policy changes in the latter half of the 1980’s. In the end, the diminishing grandeur of the Red Army in Soviet society due to the Afghanistan failures certainly facilitated the Soviet leadership’s adjustments of domestic society to include demilitarization.The Alienation of Minority Populations and the Diminishing Soviet IdentityThis segment analyzes the ways in which the Afghanistan war resulted in the alienation of minorities within the Soviet Union. Specifically, issues discussed include the distrust of Central Asian minorities as well as the ways in which the degradation of the Soviet Army role contributed. This is ultimately to determine how the Afghanistan War led to fragmentation in Soviet societies and helped highlight distinctions among different Soviet ethnic groups.First, it is pertinent to note that the Soviet Union shared a border with Afghanistan. As mentioned previously, many sources questioned whether in invading Afghanistan the Soviet Union was just pursuing a defensive strategy to protect its border. Below, Map 1 depicts the percentage of Muslims in each Soviet republic in the year 1979 – each percent range is represented by a different color. As the map shows, Muslims were the majority of the population in many of the southeastern Soviet republics. Republics such as Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan, and Tajikistan were practically homogeneous, home to Muslim populations ranging from 90 to 100 percent. When the Soviet Union invaded Afghanistan to fight the Mujahedeen, who were not only anti-communist but also Islamist, the Soviet leadership and military became concerned over potential conflicts of interest among the USSR’s Muslim populations as well as the soldiers. The Soviet Union feared that ethnic and cultural ties to the Afghans could be a potential risk for attaining Soviet military ambitions.[42] Thus, ethnic unrest rose within the Soviet army and separations between different kinds of Soviet citizens became more pronounced than ever before.Map 1

By Satenik HarutyunyanContributing WriterAbstract: The impact of Soviet involvement in the Afghan Civil War on domestic policy changes within the Soviet Union is a frequently debated topic. Scholars have also presented varying viewpoints regarding how the USSR’s role in Afghanistan affected domestic populations. There is however, limited insight concerning how both of these elements were related and the ways in which they helped shape the political environment of the Soviet Union before its collapse. Scholars attributing the changes within the Soviet Union during the late 1980’s to economic turmoil, overlook how foreign policy initiatives and the repercussions of invading Afghanistan added an important sociopolitical element, which influenced domestic policy.IntroductionSince the end of their potent wartime alliance during World War II, the Soviet Union and the United States were engaged in a perpetually fluctuating and tense conflict to assert global hegemony. Each fought relentlessly – without a direct declaration of war against the other – to emerge as the sole superpower in the global community. Regardless of whether the Cold War was a conflict of ideology, spheres of influence, or expansionism, both superpowers were consistently forming foreign policy with the aim to obstruct the rival’s goals. When the US invaded Vietnam under the pretense of saving an unstable nation from the evils of communism, the Soviet Union did not hesitate to provide arms and financial support to the Viet Cong opposition, ultimately playing a fundamental role in the embarrassing American failure. A mere decade later however, it was the US who provided continual funds and arms to the resistance movement against a Soviet invasion – this time the battleground was communist Afghanistan. The invasion of Afghanistan, dubbed the Soviet Union’s “Vietnam” by many, was a decade long struggle, which resulted in devastating military defeat and little political progress for the Soviet empire. The repercussions of the Soviet involvement however, were not only evident in Afghanistan; they also manifested themselves domestically, in the sociopolitical realm within the Soviet Union. The purpose of this paper is to explore these important domestic effects. This following research investigates the extent to which the Soviet Union's involvement in Afghanistan altered public sentiments and affected domestic populations, exploring how these social changes influenced political reform during the 1980’s.Existing Explanations: Why the Political and Social Environment of the Soviet Union ChangedThere are scholars who suggest that the inadequacies inherent in the Communist system caused an urgent need for reform within the Soviet Union during the 1980’s. They find that systematic structures such as central planning and a hierarchical bureaucracy were inefficiently executed, leading to a perpetually growing economic gap between the Soviet Union and the West, its ideological rival.[1] Some scholars also align these systematic problems with economic decline. They assert that the extensive, even radical, changes that manifested in the Soviet Union during the Gorbachev era must be attributed to the profound economic decline in the Soviet Union. Due to economic regression and turmoil, a new domestic framework was established, which in turn necessitated a decrease of foreign involvements and an overall reduction of resources allocated to defense initiatives.[2] Although these findings are compelling, they overlook a number of important sociopolitical phenomena occurring within the borders of the Soviet Union during the late 1980’s. As a result, such scholars generally ignore the impact of these phenomena on the altered political and social environment shortly before the Soviet Union’s unexpected collapse.HypothesisAfter reviewing existing research in political science literature, I aim to conduct an analysis combining domestic policy changes within the Soviet Union with the specific effect involvement in Afghanistan had on domestic populations. This deviates from conventional theories, asserting that the repercussions of the Soviet Union’s role in Afghanistan added a profound sociopolitical element previously missing in Soviet populations. I argue that involvement in Afghanistan played a contributing role in dictating domestic political reform during the second half of the 1980’s. My research will show that during this time period, partially as a result of the Soviet Union’s involvement in Afghanistan, public opinion and sentiment became important factors for Soviet political leaders. In order to confirm this hypothesis, I will analyze the role of the Soviet media as it relates to Glasnost, the role of Afghanistan War veterans in sociopolitical progress, the discrediting of the Soviet military as it pertains to domestic policy changes, as well as the alienation of minority populations within the Soviet Union. This research will span the time period of the Soviet involvement in the Afghan Civil War, focusing on the Gorbachev era to the final withdrawal of Soviet troops in 1989.Background: The Soviet Invasion and Occupation of AfghanistanIn order to illustrate the premise of the hypothesis outlined above, it is essential to understand the historical context of the Soviet Union’s role in Afghanistan. The Red Army invaded Afghanistan in December of 1979. At the time, the Soviet Union claimed the invasion was a response to request for aid from the newly established People’s Democratic Republic of Afghanistan, which was attempting to legitimize itself in an ideologically, socially, and politically divided Afghanistan. Ultimately, the precipitating event that had led to the establishment of Communist Afghanistan (and eventually the Soviet invasion), was the overthrow of former King Zahir Shah in 1973.[3] The Communist government established by the People’s Democratic Party of Afghanistan attempted to wholly and rapidly establish a socialist system within Afghanistan. This strategy, however, did not succeed in creating political stability, instead, it gave birth to the now notorious insurgency known as the Mujahedeen (predecessors of the Taliban). Throughout the conflict, the Mujahedeen received seemingly endless supply of weaponry and financial support from Western superpowers such as the US. The Afghanistan war ultimately marked the end of Détente and reignited the Cold War.[4] The Soviet invasion of Afghanistan gravely underestimated the military, economic, and social repercussions of the war. Occupation of Afghanistan lasted a decade without successfully stifling the insurgency. The following segments illustrate the domestic impacts of the Afghanistan War on the Soviet Union.The Role of the Media and Gorbachev’s GlasnostMikhail Gorbachev, the last General Secretary of the Communist Party, shocked the international community in the second half of the 1980’s when he initiated a series of radical domestic reforms designed to redefine the relationship between the Communist government and its populations. Engineered in 1985 and introduced officially in 1988, one such policy was Glasnost, which directly translates to “publicity” or “openness”.[5] The policy was designed to establish a more transparent image of the Communist government and help alleviate deep-seated feelings of government repression among the Soviet population. Some scholars believe that Glasnost laid the foundation and served as the primary catalyst for the rise of media that openly criticized the tangible shortcomings of the Soviet regime.[6] My research builds upon this to assert that there was a mutual relationship between Glasnost and the surfacing of relatively free press in the USSR. Furthermore, media coverage of the Soviet Union’s involvement in Afghanistan was an important, even axiomatic, counterpart of the departure from Communist Party lines. In this way, the Afghanistan war provided a gateway through which the media forces released by Glasnost could mobilize.From the initial invasion of Afghanistan in 1979 to the final withdrawal of troops from the war torn nation in 1989, the Soviet press’ portrayal of the Soviet intervention in the country evolved to develop an identity that was more independent of the Communist Party than ever before. At the outset, Soviet media sources functioned essentially as proxy messengers of the government, consistently reporting the strength of the Afghan Communist government and the nobility of the Soviet cause. One year after the invasion, the Krasnaya Zvezda (Red Star), a mainstream Soviet news source, concluded, “the indestructible unity of the party, government, people, army and security forces aimed at insuring Afghanistan’s territorial integrity, national independence and security…are bringing our victory closer than ever.”[7] Here, it appears as though the Soviet mission in Afghanistan was unfolding without obstacles, exactly as planned.Additionally, the media continuously upheld that the Afghanistan war was being fought by the Afghan armed forces. In these reports, the Soviet army was fulfilling its international duty and merely acting as a support system.[8] In an interview with expert Mark Galeotti, a Soviet captain by the name of Aleksandr Lukyanets recounts the following experience from 1983: “I remember I came back from a battle one day. It was a hard battle, with much bloodshed. That evening, I read the newspaper reporting how we and the Afghans planted trees together as happy friends. There was not a single word about the war. I felt deeply offended.”[9] Actual situations such as the one described in this anecdote were rare – yet in fact they were the norm portrayed in the media. Until about 1984, the Soviet press was careful to understate any Soviet military action, especially when it came to direct combat duty.[10]As time and subsequent reporting would show however, claims of a swift Soviet victory and limited Soviet involvements were gross miscalculations and fabrications that did not accurately depict the Afghanistan war. But by the second half of the 1980’s, levels of uniformity among Soviet media sources concerning the Afghan Civil War began to dwindle, paving the way for an array of reports with differing viewpoints. Importantly, press coverage showing enthusiastic support for the Soviet mission in Afghanistan was still being published and did not disappear altogether in the second half of the decade. The key point worth extracting here is that the growing incongruence among Soviet press regarding Afghanistan serves as a distinct example of the evolution of the media, and also in effect, of Soviet society. The shift in media portrayal started in 1985, when combat footage from Afghanistan began to air on Soviet television networks.[11] Additionally, the most well known Soviet newspaper, Pravda (Truth) concluded that the war in Afghanistan was not a matter of defending international socialism. Instead, the newspaper suggested a less glorified strategic reasoning, asserting that the invasion was merely a preventative undertaking to defend the USSR’s southern border.[12]Six years after the invasion, growing popular disdain for the war and the emergence of critical media coverage were making it increasingly difficult for the government and the military to mask the extent of the Soviet involvement.[13] By 1987, public input was already seen as a substantive source of information for mainstream media. An example of this was apparent in the summer of 1987, when Ogenek’s (Little Fire) war correspondent, Artem Borovik, published a three article series depicting the misery, bitterness, and wartime fatigue in the Soviet army.[14] The series was inspired entirely by letters from the public – presumably returned veterans, who will be discussed in greater detail in a separate segment of this paper. Additionally, newspapers such as Izvestya (Knowledge) began to reflect popular sentiments by establishing columns designated for public opinion polls on political issues like Afghanistan. Pravda (Truth) also began to incorporate a permanent column dedicated specifically to publishing commentaries and speeches by Western political figures.[15]Furthermore, it was at this time that the Soviet media began to publish reports of corruption and human rights violations within the Soviet army. Although a later segment of this paper will more extensively discuss the discrediting of the Soviet military, which steadily took place throughout the involvement in Afghanistan, such reports are mentioned now particularly to underline the media’s role in speaking out against an esteemed Soviet institution. Similar to the US struggle in Vietnam, the Soviet army experienced difficulties connected to widespread drug use amongst its troops during the war. Furthermore, accusations of corruption began to surface as reports of soldiers trading war equipment with the Mujahedeen in return for drugs, foods, and electronic goods made their way into mainstream Soviet media.[16] The army was also accused of heightened cruelty against civilian populations, stemming from a blurred understanding of who the Afghan enemy really was. As Galeotti argues, “there was a lack of distinction between civilian and non-civilian, hard and soft targets, legitimate and illegitimate.”[16] In terms of the military’s role in Afghanistan, the press helped to open a “Pandora’s Box on the intervention itself,”[18] as Sheik titles the phenomenon. Ogenek’s (Little Fire) Borovik pointed out this irony when he mentioned that the Soviet press could not determine who the Mujahadeen was in its reporting, thus having to rely instead on the term “the armed opposition.”[19] In this way, the press helped to articulate the vagueness surrounding the Afghanistan conflict to the rest of Soviet society. Without the war in Afghanistan, the press would not have had that opportunity to explore such unconventional reporting.The developments discussed above were certainly remarkable, if not ground breaking, due to the Soviet Union’s longstanding identity as a repressed society where freedom of speech was a far off notion. Additionally, these sociopolitical changes manifested themselves as a response to the Soviet Union’s ongoing and unsuccessful presence in Afghanistan. Thus, as this investigation of Soviet media has shown, the USSR’s foreign policy initiatives in Afghanistan influenced the drastic changes in the relationship between the Soviet government and its populations as well as in Soviet domestic policy initiatives.In a now world famous statement from 1986, Gorbachev described Afghanistan as a “bleeding wound.”[20] In many ways, when Gorbachev willingly and openly admitted policy failures, he was both reacting to signs of discontent as well as encouraging the media (and other public sources) to continue on along their new path of critique and analysis. In doing so, Gorbachev aimed to incorporate certain levels of popular discontent as a natural counterpart of political systems rather than an outlandish display of “rebellion” needing to be stifled. Without the legal privileges Glasnost allowed, the Soviet media’s emboldened autonomy would not have materialized nearly as extensively as it did during the second half of the 1980’s. However, it is also critical to consider the fact that Gorbachev and his administration felt an urgency to cultivate policies such as Glasnost in order to moderate the impact of growing public display of political criticism – as exemplified by the beginning of the media’s daring coverage of the Soviet Union’s failures in Afghanistan in 1985.The Role of the “Afghans” and Sociopolitical ProgressIn analyzing how the decade long Soviet involvement in Afghanistan dictated sociopolitical developments in the Soviet Union, it is fundamental to dissect the role of the men (and women) who served in this war – commonly nicknamed the “Afghans”. This segment of analysis demonstrates how Afghanistan war veterans actively participated in the restructuring of Soviet society through political activism unrelated to party politics. First, it is important to establish that not all “Afghans” contributed to this phenomenon. As a matter of fact, in a poll for Pravda, only about twelve percent of veterans cited politics as their primary concern.[21] That being said, activism of the “Afghans” rested not in the number of those who chose to get involved, but in the potency of their actions. There was also a relative lack of uniformity in veteran mindset regarding what exact societal and political changes should be implemented, resulting in a wide range of societal activism that the “Afghans” contributed to.According to the 1985 US News and World Report, there were already close to one million Soviet veterans who had returned from Afghanistan.[22] Official Soviet reports from the same year, however, released much smaller numbers closer to 308,000 troops.[23] Even among various Soviet sources, it is difficult to find consistency in the numbers of troops deployed. The large delta between US figures and official Soviet figures however, is not surprising considering their respective interests. For the US, exaggerating Soviet deployment numbers would impress and shock its public, helping to portray the Soviet Union’s role in Afghanistan as a vast and expansionist conquest. Accordingly, the Soviet government was careful to downplay their role in Afghanistan so as to avoid domestic scandal.[24] By the time the war was over however, the Soviet Union’s Committee for Soldier International Affairs released numbers that were closer to the actual Afghanistan deployment figure – 730,000 total troops.[25]For the veterans who took to political activism, there was a common mindset concerning two basic core issues. As expected, these similarities came into being largely as a direct result of their shared experience in the Afghanistan war. First, the veterans were concerned with morality in politics – specifically the politics of guilt and blame. Second, the veterans focused on the concept of representation and the idea of establishing elected entities to address their concerns.[26] But in order to achieve social progress toward these ambitions, the politically motivated veterans needed coordination through a legitimate method. In many ways, the city of Leningrad (present day Saint Petersburg) became the birthplace of grass-roots organization for the “Afghans” because the organizations stemming from this city focused on the “coalescence of local groups” within large cities and even broader regions.[27] These organizations provided veterans who shared a mindset regarding societal change a forum through which they could organize and eventually mobilize.One such organization, the Leningrad Association of Veterans of the War in Afghanistan (LAVVA), was formed in 1989 and acted as a unifying common ground for groups to come together. The main purpose of the organization was to harbor cooperation between local veterans’ groups, establish a common self-help program, and provide legal and social protection for the veterans of the war. The organization though broad in its nature, worked in close accordance with specified local groups such as the Union of Mothers of the Dead and the Invalids’ Union.[28] The purpose of the broader organization was to cater to goals and ambitions commonly found among such distinct groups. The presence of such displays of cooperation was evidence of a developing political network stemming from grass roots mobilization. This kind of political organization was certainly not commonplace in the Soviet Union prior to the Afghanistan war.Furthermore, as a result there was a rise in consensus within the “Afghan” coalition for the need of a national level body to articulate its views.[29] Here, it is clear the politically motivated veterans were seeking social progress and representation for the entirety of the veteran population. Consequently, two large-scale organizations were formed in order to represent the unity of the “Afghans” and their needs on a national level. These organizations were the Union of Veterans of Afghanistan (SVA) and the All Union Association of Reserve Soldiers’ Councils, Soldier-Internationalists and Military – Patriotic Unions (the Association). The SVA, which ran on a budget of 7,000,000 rubles (980,000 USD) and had official membership exceeding an impressive 300,000 people, adamantly focused on providing material help to veterans and their families. Thus it was “an organization devoted to the redistribution rather than the creation and acquisition of resources,” as Galeotti explains.[30] On the other hand, the Association, an organization comprised of a central body with four elements, included Dolg (Duty) and the Economic-Production Commission. The purpose of the former was to help invalid veterans while the latter focused on economic education and entrepreneurship.[31]After recognizing the missions of these organizations and the method by which they achieved their goals, it is essential to note that such organizations did not hold ties to the Communist party. As a matter of fact, they helped mark the beginnings of non-party aligned politics. This was a new trend in Soviet society, considering that the Communist Party had traditionally penetrated all facets of political and social life.[32] Because the Soviet leadership was adamant in concealing the true extent of involvement in the war, it also to a certain extent had to ignore the concerns and presence of the “Afghans”.[33] Without a stable flow of material or psychological support from the government, it is only logical that politically motivated veterans deviated from the government’s mission and established alternate ways to make their concerns known. Thus the Afghanistan war, and the discontent it brought to the veterans who served in it, planted the seeds of a political movement independent of the Communist Party and its ideals.The veterans of Afghanistan continued to become more influential in the political realm as they began participating in the Soviet bureaucracy and even holding public offices. These occurrences mainly began to take place in the latter half of 1989, which narrowly surpasses the timeframe addressed in this paper. Although I avoid delving deeply into that chapter of “Afghan” political activism, I do wish to point out a salient example of how this participation helped the “Afghans” directly impact Soviet political society. By the beginning of 1990, the Soviet government had instated a committee called the Supreme Soviet Committee for Soldier-Internationalists’ Affairs in efforts to respond to the needs of the “Afghans”. The Committee proved to be effective and within just three months of its inception, it successfully fought for a 50 percent tax discount for veterans. The Committee also ensured that all veteran organizations be exempt from government taxes.[34] In this way, the “Afghans” in the swiftly changing Soviet government helped to advance the goals of politically motivated “Afghan” organizations.From local specific organizations to national level groups to government involvement, the Afghanistan War veterans mobilized to initiate change in the way they were treated by the Soviet government and the place they held in society. Therefore, the conclusion can be drawn that political activism of the “Afghans” did result in material progress.The Social and Domestic Context of Discrediting of the Soviet MilitaryThe Soviet Union’s military failure in Afghanistan is an important factor to consider when analyzing the ultimate domestic sociopolitical impact of the Afghanistan war on the USSR. In asserting this, it must be recognized that on the surface the link between these two elements may seem abstract. Therefore, in order to fully apprehend how the military failure in Afghanistan contributed to changing domestic populations and societies, it is essential to understand how Soviet leadership’s and popular perceptions of the military began to shift throughout the decade long involvement in Afghanistan.First, it is important to establish what role the Soviet military played in society prior to the Afghanistan invasion. In many ways, the Soviet military was a pillar of Soviet society. After its endeavors during the Second World War, the Soviet military became a pinnacle of Soviet identity and its prestige was universally recognized throughout its populations. Reuveny and Prakash go so far as to depict the Soviet military as a “microcosm of the Soviet society,” because it harbored soldiers from many nationalities, with a focus on defending the ideological missions of the Soviet Union.[35] In this way, the army was a binding force of otherwise distinct Soviet societies not only due to its sanctified position in Soviet society, but also because of neglected ethnic differences.With the Soviet military’s traditional purpose in society established, it is then important to discuss how that identity changed as well as how Soviet military prestige diminished as a result of the Afghanistan war - thus altering this staple pillar of Soviet society. When the Soviet Union invaded Afghanistan, it grossly miscalculated the strength of their Mujahedeen enemy. Initially, Soviet strategists anticipated brief involvement in the civil war, hasty victory, and a prompt withdrawal.[36] Consequently, the USSR’s outright inability to defeat the insurgency came largely as a surprise, and efforts developed into a ten year-long struggle to no avail. Although the Soviet Union’s military failure against the Mujahedeen is a fascinating and complex topic, for the purpose of remaining focused on domestic and sociopolitical impacts, I avoid delving deeply into the specific (and important) hindrances to the Soviet goal such as US and Pakistani involvement, constant reorganization of the enemy, and the nature of mountain warfare in Afghanistan.By the mid 1980’s and particularly during Gorbachev’s era, there emerged a drastic and pivotal divide between the Soviet military and the Soviet government leadership. This concept was relatively foreign to the Soviet Union, especially because those two entities were traditionally interdependent when it came to their main ideological purpose: to support communism. As mentioned earlier however, the severe shortcomings of the Soviet Union in the Afghanistan conflict could no longer be denied.[37] As a result, the Communist leadership acted strategically in distinguishing itself from the Soviet military. This explains why the leadership adamantly assumed the position of publicly scorning the military and its incompetency in Afghanistan.Eduard Shevardnadze, the First Secretary of the Georgian Communist Party and the Soviet Foreign Minister at the time, released numerous statements articulating how USSR leadership was not responsible for the failures in Afghanistan. In 1986, Shevardnadze shared with Pravda the leadership’s mentality as it pertained to Afghanistan; he specified the following for the record: “Not having chosen this legacy for ourselves [but] accepting it for what it is, we are also obliged to take decisions as to how to deal with it from here on.”[38] Here Shevardnadze is directly implying that the leadership in power in 1986 was not responsible for the decision to invade Afghanistan, nor was it to blame for the lack of military success following the invasion.The blame-shifting that originated during the Afghanistan war – and the consequent Soviet military’s discrediting – created a new facet of Soviet society, one in which the two most important pillars of defending socialism were at ideological and practical odds with one another. This sort of public disagreement between auxiliary Soviet institutions, which was particularly highlighted thanks to the media exposure explained earlier, was indeed a previously unknown phenomenon for Soviet society. In his analysis of the Soviet military, Taylor points out, “the military, accustomed to a sacrosanct position in Soviet society, came under intense criticism in the liberal media on topics such as conditions in the armed forces and the size of the “military-industrial complex.”[39] Taylor’s point is salient as it deliberately underlines how the structure and integrity of the Soviet army was being blatantly questioned through public forums.Not only was the diminishing prowess of the military an issue on the social level, it even transcended to the realm of domestic policy during Gorbachev’s massive campaign to redesign the internal structure the USSR. Because it was in the Soviet Union’s best economic interests to reconsider foreign spending, the outcome of Afghanistan became of essence to domestic Soviet policy-making procedures. The Gorbachev coalition’s reform initiatives such as Perestroika (Restructuring), made domestic economic interests the focal determinant of foreign policy measures.[40] As a result, foreign expenditures needed to maintain Afghanistan were compromised, further placing the military at blatant odds with Soviet leadership motives. As Reveuny and Prakash suggest, “since a major focus of Perestroika and Glasnost was the demilitarization of Soviet society, the war emerged as a rallying point against the military.”[41] This statement synthesizes the distinct points addressed in this section and helps to socio-politically contextualize domestic policy changes in the latter half of the 1980’s. In the end, the diminishing grandeur of the Red Army in Soviet society due to the Afghanistan failures certainly facilitated the Soviet leadership’s adjustments of domestic society to include demilitarization.The Alienation of Minority Populations and the Diminishing Soviet IdentityThis segment analyzes the ways in which the Afghanistan war resulted in the alienation of minorities within the Soviet Union. Specifically, issues discussed include the distrust of Central Asian minorities as well as the ways in which the degradation of the Soviet Army role contributed. This is ultimately to determine how the Afghanistan War led to fragmentation in Soviet societies and helped highlight distinctions among different Soviet ethnic groups.First, it is pertinent to note that the Soviet Union shared a border with Afghanistan. As mentioned previously, many sources questioned whether in invading Afghanistan the Soviet Union was just pursuing a defensive strategy to protect its border. Below, Map 1 depicts the percentage of Muslims in each Soviet republic in the year 1979 – each percent range is represented by a different color. As the map shows, Muslims were the majority of the population in many of the southeastern Soviet republics. Republics such as Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan, and Tajikistan were practically homogeneous, home to Muslim populations ranging from 90 to 100 percent. When the Soviet Union invaded Afghanistan to fight the Mujahedeen, who were not only anti-communist but also Islamist, the Soviet leadership and military became concerned over potential conflicts of interest among the USSR’s Muslim populations as well as the soldiers. The Soviet Union feared that ethnic and cultural ties to the Afghans could be a potential risk for attaining Soviet military ambitions.[42] Thus, ethnic unrest rose within the Soviet army and separations between different kinds of Soviet citizens became more pronounced than ever before.Map 1 In his account of the Afghanistan war, Galeotti includes the following reflection from a veteran of the war: “You could never trust the blacks [i.e. Central Asians]. We had some of them lying around, but the real work was always done by the Russians and the Ukrainians.”[44] Accounts like this illustrate the growing sensitivity to ethnic identity within the Soviet Union. In the USSR’s Central Asian republics, the war was commonly seen as a “foreign cause.” Radio Liberty research finds that citizens felt disconnected from the war and believed that their men were dying for an “alien” cause.[45] Even though many Soviet citizens questioned the purpose of the USSR’s involvement in Afghanistan, this specific sense of alienation is especially noteworthy because the Soviet minority in question began to no longer feel a connection to the Soviet Union itself. During this era, Soviet identity centered on socialist ideology and community was slowly yet surely withering, and the repercussions of the Afghanistan war expedited this process.In terms of Soviet minority populations, the Afghanistan war and the USSR’s military shortcomings helped destroy the image of Soviet invincibility. This is applicable on both the military as well as political level. Concerning minority populations, Reneuvy and Prakash argue that “it [the war] alienated both elites and masses and gave the secessionist movements a popular rallying cause against Russian domination.”[46] In this way, the universally unpopular war helped lay the premise for minority populations to question their role in Soviet society. Historically, the Soviet Union was extremely careful to make sure, sometimes with the use of military force, that nationalists’ movements would not evolve into viable threats to the Union.[47] But since the Soviet military did not succeed in achieving its goals throughout its decade long involvement in Afghanistan, the once omnipotent Soviet system showed signs of fallacy and conquerability.Given the confines of this paper, I do not go into depth about speculations regarding whether or not the impacts of the Afghanistan war were the primary reason for why these nationalist movements eventually expanded and turned into secessionist movements to declare independence from the Soviet Union. However, it is acknowledged that the effects of the war perpetuated ethnic distinctions, undermined Soviet unity, and aided in the dismantling of the Soviet system’s superiority.ConclusionThere is no question that the Afghanistan war was the Soviet Union’s final large-scale military venture before its collapse. The debate over its role in the USSR’s dissolution however, has been waged among scholars with little universal consensus. For many scholars, it is all too coincidental that just one year after the final withdrawal of Soviet troops from a still war torn Afghanistan, the Soviet Union was dismantled into fifteen separate countries. Conversely, it is also true that to a large number of scholars and leaders in the international community, the dissolution of the Soviet Union was still largely unforeseeable even in 1989. My research has presenting the ways in which the Afghanistan war was significant to sociopolitical and domestic policy changes in the Soviet Union. To this end, I investigated the role of the Soviet media in accordance with Glasnost, the role of the Afghanistan veterans in sociopolitical progress, the discrediting of the Soviet military and the ways it relates to domestic policy changes, as well as the alienation of minority populations within the Soviet Union. This analysis can prove useful in understanding the significance of these factors to the dissolution of the Soviet Union alongside other important determinants at the time of the collapse.Image by USAF Senior Airman Kenny Holston.Endnotes[1] Ikle, Charles. “Comrades in Arms: The Case for Russian-American Defense Community.” The National Interest, 26 (Winter, 1992), 28.[2] Mendleson, Sarah. “Internal Battles and External Wars: Politics, Learning, and the Soviet Withdrawal from Afghanistan.” World Politics, Vol. 45, No. 3 (Apr., 1993), Princeton University Press, Princeton., Evangelista, Matthew. ‘The Paradox of State Strength: Transnational Relations, Domestic Structures, and Security Policy in Russia and the Soviet Union’, International Organization Vol. 49, No. 1 (winter, 1995)[3] Cordovez, Diego and Harrison, Selig. Out of Afghanistan. New York: Oxford University Press, 1995, 14.[4] Comisso, Ellen, Class Lecture. Political Science 142Q: The Cold War. University of California, San Diego, La Jolla, CA. 1 February 2011.[5] Comisso, Ellen Class Lecture. Political Science 142Q: The Cold War. University of California, San Diego, La Jolla, CA. 10 February 2011.[6] Evangalista, 11.[7] Downing, John H.D. "Trouble in the Backyard: Soviet Media Reporting on the Afghanistan Conflict." Journal of Communication. Vol. 38 No.2 (1988), 22.[8] Reuveny, Rafael and Prakash, Aseem. “The Afghanistan War and the Breakdown of the Soviet.” Review of International Studies, Vol. 25, No. 4 (Oct., 1999), 705.[9] Galeotti, Mark. Afghanistan: the Soviet Union's Last War. London: Newburry House, 1995, 60.[10] Sheik, Ali. "Not the Whole Truth: Soviet and Western Media Coverage of the Afghan Conflict1." Conflict Quarterly. (1990), 79-82.[11] Downing, 22.[12] Reuveny and Prakash, 707.[13] Downing, 18-24.[14] Reveuny and Prakash, 703.[15] Sheik, 81.[16] Reveuny an Prakash, 705[17] Galetotti, 69.[18] Sheik, 84.[19] Ibid.[20] Downing, 7.[21] Galeotti, 121.[22] US News and World Report (December 1985), 15.[23] Military Balance (Figures until 1985).[24] Reveuny and Prakash, 701.[25] Galeotti, 30.[26] Ibid., 121.[27] Ibid., 113.[28] Ibid.[29] Galeotti, 114.[30 Ibid.[31] Ibid.[32] Comisso, Ellen. Class Lecture. Political Science 142Q: The Cold War. University of California, San Diego, La Jolla, CA. 13 January 2011.[33] Reveuny and Prakash, 705.[34] Galeotti, 121.[35] Reuveny and Prakash, 701.[36] Comisso, Feb. 1, 2011.[37] Downing, 18-24.[38] T. H. Rigby, 'The Afghan Conflict and Soviet Domestic Polities', in J. W. Lamare (ed.), International Crisis and Domestic Politics: Major Political Conflicts in the 1980s (Westport, CT: Praeger, 1991), 144.[39] Taylor, 61.[40] Sheik, 1988 1173.[41] Reveuny and Prakash, 701.[42] Nahaylo, Bodhan. Soviet Disunion. New York: The Free Press, 1990, 233.[43] University of Texas Libraries[44] Galeotti, 27.[45] Reuveny and Prakash, 708.[46] Reuveny and Prakash, 704.[47] Comisso, Jan. 13 2011.

In his account of the Afghanistan war, Galeotti includes the following reflection from a veteran of the war: “You could never trust the blacks [i.e. Central Asians]. We had some of them lying around, but the real work was always done by the Russians and the Ukrainians.”[44] Accounts like this illustrate the growing sensitivity to ethnic identity within the Soviet Union. In the USSR’s Central Asian republics, the war was commonly seen as a “foreign cause.” Radio Liberty research finds that citizens felt disconnected from the war and believed that their men were dying for an “alien” cause.[45] Even though many Soviet citizens questioned the purpose of the USSR’s involvement in Afghanistan, this specific sense of alienation is especially noteworthy because the Soviet minority in question began to no longer feel a connection to the Soviet Union itself. During this era, Soviet identity centered on socialist ideology and community was slowly yet surely withering, and the repercussions of the Afghanistan war expedited this process.In terms of Soviet minority populations, the Afghanistan war and the USSR’s military shortcomings helped destroy the image of Soviet invincibility. This is applicable on both the military as well as political level. Concerning minority populations, Reneuvy and Prakash argue that “it [the war] alienated both elites and masses and gave the secessionist movements a popular rallying cause against Russian domination.”[46] In this way, the universally unpopular war helped lay the premise for minority populations to question their role in Soviet society. Historically, the Soviet Union was extremely careful to make sure, sometimes with the use of military force, that nationalists’ movements would not evolve into viable threats to the Union.[47] But since the Soviet military did not succeed in achieving its goals throughout its decade long involvement in Afghanistan, the once omnipotent Soviet system showed signs of fallacy and conquerability.Given the confines of this paper, I do not go into depth about speculations regarding whether or not the impacts of the Afghanistan war were the primary reason for why these nationalist movements eventually expanded and turned into secessionist movements to declare independence from the Soviet Union. However, it is acknowledged that the effects of the war perpetuated ethnic distinctions, undermined Soviet unity, and aided in the dismantling of the Soviet system’s superiority.ConclusionThere is no question that the Afghanistan war was the Soviet Union’s final large-scale military venture before its collapse. The debate over its role in the USSR’s dissolution however, has been waged among scholars with little universal consensus. For many scholars, it is all too coincidental that just one year after the final withdrawal of Soviet troops from a still war torn Afghanistan, the Soviet Union was dismantled into fifteen separate countries. Conversely, it is also true that to a large number of scholars and leaders in the international community, the dissolution of the Soviet Union was still largely unforeseeable even in 1989. My research has presenting the ways in which the Afghanistan war was significant to sociopolitical and domestic policy changes in the Soviet Union. To this end, I investigated the role of the Soviet media in accordance with Glasnost, the role of the Afghanistan veterans in sociopolitical progress, the discrediting of the Soviet military and the ways it relates to domestic policy changes, as well as the alienation of minority populations within the Soviet Union. This analysis can prove useful in understanding the significance of these factors to the dissolution of the Soviet Union alongside other important determinants at the time of the collapse.Image by USAF Senior Airman Kenny Holston.Endnotes[1] Ikle, Charles. “Comrades in Arms: The Case for Russian-American Defense Community.” The National Interest, 26 (Winter, 1992), 28.[2] Mendleson, Sarah. “Internal Battles and External Wars: Politics, Learning, and the Soviet Withdrawal from Afghanistan.” World Politics, Vol. 45, No. 3 (Apr., 1993), Princeton University Press, Princeton., Evangelista, Matthew. ‘The Paradox of State Strength: Transnational Relations, Domestic Structures, and Security Policy in Russia and the Soviet Union’, International Organization Vol. 49, No. 1 (winter, 1995)[3] Cordovez, Diego and Harrison, Selig. Out of Afghanistan. New York: Oxford University Press, 1995, 14.[4] Comisso, Ellen, Class Lecture. Political Science 142Q: The Cold War. University of California, San Diego, La Jolla, CA. 1 February 2011.[5] Comisso, Ellen Class Lecture. Political Science 142Q: The Cold War. University of California, San Diego, La Jolla, CA. 10 February 2011.[6] Evangalista, 11.[7] Downing, John H.D. "Trouble in the Backyard: Soviet Media Reporting on the Afghanistan Conflict." Journal of Communication. Vol. 38 No.2 (1988), 22.[8] Reuveny, Rafael and Prakash, Aseem. “The Afghanistan War and the Breakdown of the Soviet.” Review of International Studies, Vol. 25, No. 4 (Oct., 1999), 705.[9] Galeotti, Mark. Afghanistan: the Soviet Union's Last War. London: Newburry House, 1995, 60.[10] Sheik, Ali. "Not the Whole Truth: Soviet and Western Media Coverage of the Afghan Conflict1." Conflict Quarterly. (1990), 79-82.[11] Downing, 22.[12] Reuveny and Prakash, 707.[13] Downing, 18-24.[14] Reveuny and Prakash, 703.[15] Sheik, 81.[16] Reveuny an Prakash, 705[17] Galetotti, 69.[18] Sheik, 84.[19] Ibid.[20] Downing, 7.[21] Galeotti, 121.[22] US News and World Report (December 1985), 15.[23] Military Balance (Figures until 1985).[24] Reveuny and Prakash, 701.[25] Galeotti, 30.[26] Ibid., 121.[27] Ibid., 113.[28] Ibid.[29] Galeotti, 114.[30 Ibid.[31] Ibid.[32] Comisso, Ellen. Class Lecture. Political Science 142Q: The Cold War. University of California, San Diego, La Jolla, CA. 13 January 2011.[33] Reveuny and Prakash, 705.[34] Galeotti, 121.[35] Reuveny and Prakash, 701.[36] Comisso, Feb. 1, 2011.[37] Downing, 18-24.[38] T. H. Rigby, 'The Afghan Conflict and Soviet Domestic Polities', in J. W. Lamare (ed.), International Crisis and Domestic Politics: Major Political Conflicts in the 1980s (Westport, CT: Praeger, 1991), 144.[39] Taylor, 61.[40] Sheik, 1988 1173.[41] Reveuny and Prakash, 701.[42] Nahaylo, Bodhan. Soviet Disunion. New York: The Free Press, 1990, 233.[43] University of Texas Libraries[44] Galeotti, 27.[45] Reuveny and Prakash, 708.[46] Reuveny and Prakash, 704.[47] Comisso, Jan. 13 2011.