SEVENTY-FIVE DAYS IN RWANDA

By R. Sky BrownWhen most Americans think of Rwanda, our minds tend to go to one word: genocide. In April of 1994, over seventeen years ago, genocide ravaged the country and casualties were everywhere — particularly in the southeastern sector. This is where I stayed earlier this year, in the village of Gashora, in Bugesera District. I lived in Gashora for a little over two months, and the first thing I’d like to clarify about my experience is that I would never have guessed Rwanda’s painful past when visiting the country today. While there I found the landscape to be absolutely stunning, the people to be very friendly, the systems of education and the interior to be fast-growing and the government to be very stable. In fact, I almost feel like a traitor to what I consider to be my newly adopted country, by beginning this article mentioning the genocide. However, most of the people that I’ve talked to about my trip since my return, and this includes friends, family and strangers, have expressed concern or confusion — how could I go to Rwanda and come back so satisfied, happy and, well, alive?They don’t seem to realize how much can change in almost two decades. They think that Rwanda is in the same state now that it was then, that it is an unstable place where violence can erupt at any moment. This is completely untrue. In fact I would say that Rwanda is a very safe country, and one that’s turning a new leaf.My personal experience in Rwanda focused around education. For three months, from August to November 2011, I was an English tutor at Gashora Girls Academy of Science and Technology (GGAST). It is a girls-only school currently with ninety students of 14 to 22 years of age, all in secondary school year four. This is about the equivalent of American sophomore year in high school. The school has just completed its first year with its first class of students. Eventually they will have 270 students in secondary school grades four, five and six.While this school is the dream-child of two women in Seattle, and is currently American-financed, their long-term goal is to make the school self-sufficient and self-sustaining, supported by 30 acres of farmland and taught only by Rwandan teachers. Since the school only just finished its first year, there are still a lot of kinks in the process of being fixed. As the next two years pass and one hundred and eighty more students are added to the current ninety, I’m sure there will be plenty more challenges as well, but also a capable staff to overcome them.While staying at the school and living in the dorms, I learned a lot from the country, other teachers and particularly my estimable students, who showed me that some things are truly universal.

The above photo is a view of a few of the classrooms at GGAST. The building on the left houses the biology and chemistry classrooms. The building to the right is the computer lab, library and administrative offices. In front of the computer lab is the Rwandan flag. This picture was taken in October, after the rainy season began and all the grass came back to life.The computer lab is state-of-the-art, as far as I understand it, and uses six Windows MulitPoint Server host computers. The school also uses about ninety of the “One Laptop Per Child” small, green, alien-looking laptops, complete with little plastic antennas. The girls use these on Saturdays to check Facebook and email their parents. The entire school has relatively stable Wi-Fi.

This picture shows the inside of the school’s dining hall, where the students, in their uniforms, eat breakfast.Our lunch and dinner meals generally included rice, brown beans, tomatoes, green beans, beef, pasta and fresh bread, with the lucky treat of butter or peanut butter or honey. It was extremely delicious — although sometimes lacking in variety. The cook Anisette was formerly employed as a hotel chef and was definitely a treat for us.

This is the school’s farm — the source of much of its food — at sunset. In the foreground are pineapples, a delicious treat that looks rather odd before being picked. Farming is done by hired hands and not by students or faculty, except on very rare occasions.The last Saturday of each month is a national community service day known as umuganada. This is part of reconciliation and involves all Rwandans spending a few hours in the morning volunteering in their community. One month while I was at the school this meant the teachers and the students went out onto the farm to plant beans and haul brush.

These are English Class B students in the English classroom.English classes at GGAST are divided into A, B and C. A was the most advanced, and C the least. For the most part I worked with the C class, who spoke the least English. Most of them were students at French-speaking schools up until this year, although the main language spoken informally in Rwanda is Kinyarwanda, particularly in the villages. This means that young Rwandans are raised to be trilingual. This also means that switching to an English-only school can be a bit of a challenge.

This is a photo of me with my English club, made up of all C class students, on a day where we did a drawing-based project. Teaching was definitely a challenge for me after so many years of being a student, but it was one that I mostly enjoyed. There was also a bit of an accent barrier between the students and I — they weren’t used to my flat American vowel sounds. I tried to adopt an accent close to the way that Rwandans speak English. Nobody ever directly teased me about it, so I like to believe that it helped.

This picture is from what was one of the most memorable weekends of my trip. After I’d been at the school for a few weeks, the administration announced that the dorms were going to be sprayed against bugs, mostly to ward away malaria-infested mosquitoes. As a consequence, residents of the dorm had to evacuate, bringing their mattresses and personal belongings outside for the afternoon. While we may have looked a bit like a refugee camp, the girls loved lounging outside on their mattresses and talking with their friends.Unfortunately, this corresponded with one of the first days of the rainy season (as you can see, the grass was still pretty dry and brown before the rains began). In the middle of the afternoon it began to rain and the girls all had to transport almost two hundred mattresses and ninety suitcases into the unused end of the dining hall before they were soaked.

Pacifique, Divine, Yvonne and Sandra reading the school journalism club’s first publication on the last day of school. Clubs, which were held for about an hour and a half on Tuesday and Friday afternoons, included journalism, health, architecture and my own English club, to name a few.

Small monkeys like this were some of the only wildlife, besides eagles, that I saw while at school. He and his troop lived in the trees at the edge of the lake. Apparently they like to steal papayas from the farm.Rwanda’s most famous wildlife is the mountain gorillas, which are even featured on their 5,000 Rwanda Franc notes. Unfortunately, it’s a bit of a hike to go see them and tourist visas are rather expensive, so I didn’t make it there this time. But I was happy with their smaller relatives.

This is a picture of Gisele, the dorm matron, nurse and a particular friend of mine, showing off a few traditional Rwandan baskets. Women from Gashora village wove these by hand to sell at a women’s collective about a third of a mile from the school.

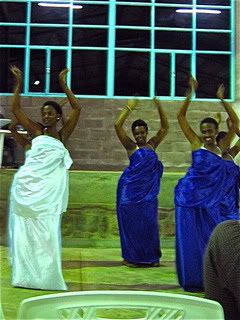

On the students’ last night at the school they put on a talent show for the staff. These girls are performing a traditional Rwandan dance in the customary attire. This dance where their arms are raised above their heads, I was told, is supposed to represent cattle — which are highly valued in Rwandan culture. The dance is all about rhythm and subtle yet fluid movements. A few students tried to teach me, but the results were not so good.

While I spent the majority of my time at school, I did leave on occasion. I took this picture while visiting Gashora Bwenge in Kamonyi District with a Peace Corps volunteer who will be working at GGAST next year. Kamonyi is hilly, like Gashora, but with much steeper hills and fewer lakes. I still found the landscape quite breathtaking.This is, as far as I understand it, the town where the Peace Corps trains its Rwanda volunteers for three months before sending them to a site. Volunteers live a much less cushy life than the one I enjoyed at GGAST. They go without the creature comforts of pre-cooked food, showers, purified tap water and flush toilets, all of which I, and all the other school residents, were lucky enough to have. However they are trained in Kinyarwanda, which would have been a very helpful addition to my own cultural education.

I also spent time in Kigali about a week after school ended, which is the capitol of Rwanda and by far its largest city. The city has almost one million residents, but as most buildings are only one story, it is a sprawling city roaming across hill after hill. I never doubted the accuracy of Rwanda’s nickname of the “land of one thousand hills.” I also understood why motorcycle taxis were such a popular form of travel.

On one of my last days I stopped by the Kigali Genocide Memorial Centre, which is a museum that talks about genocide across the world, with one large exhibit about Rwanda on the bottom floor.I cried while listening to video testimonials from survivors. One husband talked about how when a killer came into his home, his wife’s maid refused to leave her mistress’ side. The killer sliced both women down with a machete, side by side.I took this picture outside the museum, at a mass grave where 250,000 genocide victims are buried.

Another day I went to visit a Kigali nursery and primary school that was having an end-of-year festival. One part of this celebration included a “getting dressed” competition among four-year-old nursery school students. These five competitors stood in the performance area in their underwear and socks and were told to put on their uniforms, including shoes, by themselves — just like big kids. It was extremely adorable watching them try to figure it out as parents and friends cheered them on. One girl spent about five minutes trying to button her shirt, without much success. Two of the boys ended up with their shorts on backwards.I know that I was in Rwanda for a relatively short time, but I greatly enjoyed it. I honestly feel like it is my second home, and some of the people I met are now like family to me.Rwanda may be burdened with an extremely painful past, not dissimilar to that of Germany post-WWII, but the country is recovering with beauty and grace. Of course there is still some tension — it is hard to dismiss the loss of 800,000 lives. In a country as small as Rwanda, every single citizen feels the impact of such a loss, even decades later. But such a past does not preclude a bright future. I think, and so I believe, does Rwandan President Paul Kagame, that education is the cornerstone to that future. Schools like GGAST, especially those for girls who were previously overlooked or ignored, can bring a strong, dedicated country like Rwanda into a future where they can compete intellectually with other countries around the world.Photo courtesy of R. Sky Brown