A MURAMBATSVINA EDUCATION: ZIMBABWEAN CHILDREN DENIED THEIR CIVIL RIGHTS

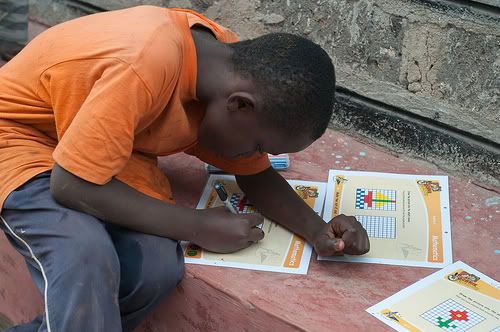

By Nisha BhaktaStaff WriterZimbabwe, once known for having one of the best educational systems in Africa, has taken a turn for the worst in recent years. The cause? A combination of hyperinflation and political controversy. The economic crisis started in 2000 when the Zimbabwean government severely impacted the agricultural industry by displacing farmers from their land. Zimbabwe’s economy immediately went into a recession and inflation began to rise. In 2000 the primary school attendance was at 90 percent, however by 2003 it had fallen to 65 percent. Although it made huge strides forward in terms of bettering its educational standards after its independence, Zimbabwe’s hyperinflation has caused schools to be exceptionally under-funded. Thousands of qualified teachers were also forced to relocate due to the fact that their salaries were not keeping up with the inflation. However, several teachers have come forward to state that they fled for political reasons.The Zimbabwean government believes that teachers tend to support the opposition and have used violence to intimidate them. The ZANU-PF has been the ruling government of Zimbabwe since its independence from Britain 1980. With its secure footholds, the ZANU-PF experienced no real political opposition until twenty years after its conception by the MDC. The 2000 elections, which the ZANU-PF eventually won, are considered by many international critiques to be neither free nor fair. Forty-eight days after the general election, Operation Murambatsvina was implemented. The government gave the following “justification for the operation: arresting disorderly or chaotic urbanization, including its health consequences; stopping illegal, parallel market transactions, especially foreign currency dealing and hoarding of consumer commodities in short supply; and reversing environmental damage caused by inappropriate urban agricultural practices.” On the contrary, the people affected and targeted by the operation speak to other motives. Zimbabwe’s failing economy mixed with Operation Murambatsvina and its political roots resulted in a cocktail of human rights violations. Operation Murambatsvina In 2005 the government program known as Operation Murambatsvina (Drive out Trash) was implemented, causing the forced eviction of 700,000 people from urban areas across the country. Promising a better life, it demolished the slums in all major cities. The evictions are believed to be an attempt by the Zanu-PF to stem growing support for the MDC in the nearing elections. Those who have suffered the most and continue to suffer today are the youth. Although promised better housing and schooling, reports show that the poor who were evicted are now living in worse conditions than before. Six years after resettlement, the government has still failed to build schools for the thousands of children that were displaced. The forced evictions which caused most people to lose their jobs, rising inflation rates and lack of schools have made it nearly impossible for the displaced children to receive an education. As a result, makeshift schools have cropped up throughout the settlements, but with little to no funding and scarce resources a proper education is nowhere near to be found. Quality of Life The lack of education has had a significant impact on the quality of life of the evicted youth. A report released from Amnesty International in October of 2011 stated that the education of 222,000 children in primary and secondary schools were disrupted by the evictions. A situational analysis done by the UN shows that almost half of the children from 2005-2010 did not go on from primary to secondary school. Starving for a better education, thousands of children have had to resort to leaving their families behind and make the dangerous journey alone into South Africa. In addition to crossing the dangerous Limpopo river which separates Zimbabwe and Africa with its crocodiles, snakes and unpredictable currents, the children still face the threat of thieves and gangs in the lawless no-mans’-land between the river and electric fence which lines the South African boarder. A youth who made it across stated how he was attacked by a gang of armed thieves (rumored to be former Zimbabwean soldiers) called the Magomagoma who robbed him while threatening him with a knife between his legs. They then forced him to watch as other men captured by the gang were made to rape young girls. Even if they manage to make it across into South Africa the children, with no money and no shelter, sleep on the streets or on the floors of churches. These children, now illegal immigrants, earn a living in whatever way they can---some beg and others get involved with older teens who drink and sniff glue. Despite all of the dangers the few success stories that have emerged continue to generate flocks of children who make the harrowing trip. Xoliswa Sithole (a South-African film-maker) commented, “When I lived in Zimbabwe in my twenties, there were hardly any street children in Harare. Children are now not only living on the streets, they are giving birth on the streets. A second generation of street children is growing up.” Whether they stay or go, these “Forgotten Children” (as Sithole dubs them) have had their once bright futures snuffed out before their eyes. Gender Roles In terms of gender, the forced evictions have had a higher impact on the educational opportunities for girls in comparison to boys. The historical and cultural barriers that inhibit females from receiving an education have been heightened and added to by the effects of the evictions. Plan International comments that “sexual harassment and abuse by even school teachers and parents, cultural issues, lack of school fees, early marriage, parental commitments and early pregnancies are some of the contributing factors to the dropout by the girl child.” With the lack of an education, many of the girls have resorted to sex work in order to support themselves and their families. Others who wish to avoid sex work choose to get married early in order to have someone who can support them. The legal age of sexual consent in Zimbabwe is sixteen, for marriage it is eighteen for boys and sixteen for girls. However girls as young as thirteen have been reported to enter into sexual relationships with older men and get married in order to escape poverty.The option of sending children to schools located farther away has provided no relief. The trip itself is dangerous; several children have been hit by motor vehicles over the past six years. For girls in particular there is the threat of rape while making the trip and at school. In school, the children are bullied and ostracized by their peers because they come from the makeshift settlements. A recent study show that the effects heightened by the evictions, namely poverty and abuse, have caused an alarming dropout rate in female attendance at school. A third of Zimbabwean girls have stopped attending primary school and 65 percent have stopped attending secondary school. Without the opportunities provided by a higher education, young girls are limited to sexual and subversive roles. The evictions also caused those with HIV and AIDS to no longer have access to care, and more than 79,500 people over the age of fifteen have been displaced. With their lack of knowledge and sexual lifestyle, young girls have a higher risk of infection and more rapid progression of the disease. Rights The lack of education itself is considered a human rights violation under the international human rights law. The United Nations Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights states that education plays a “vital role” in promoting human rights and alleviating poverty and its effects. Education reduces the violation of other human rights such as child labor, health and discrimination. It also reduces societal issues such as early marriage, which often undermine human rights, and promotes more interaction in public affairs. Zimbabwe is required under various human rights treaties to provide education that is compulsory and available to all. Before Operation Murambatsvina, education was not free, compulsory or available to all but significant strides towards better education were being made. However after Operation Murambatsvina, this progress not only halted but has, and continues to, retrogress. Despite pressures from various organizations such as Amnesty International and promises from the government, no real progress has been made to date.Courtesy of Konstantinos Dafalias

By Nisha BhaktaStaff WriterZimbabwe, once known for having one of the best educational systems in Africa, has taken a turn for the worst in recent years. The cause? A combination of hyperinflation and political controversy. The economic crisis started in 2000 when the Zimbabwean government severely impacted the agricultural industry by displacing farmers from their land. Zimbabwe’s economy immediately went into a recession and inflation began to rise. In 2000 the primary school attendance was at 90 percent, however by 2003 it had fallen to 65 percent. Although it made huge strides forward in terms of bettering its educational standards after its independence, Zimbabwe’s hyperinflation has caused schools to be exceptionally under-funded. Thousands of qualified teachers were also forced to relocate due to the fact that their salaries were not keeping up with the inflation. However, several teachers have come forward to state that they fled for political reasons.The Zimbabwean government believes that teachers tend to support the opposition and have used violence to intimidate them. The ZANU-PF has been the ruling government of Zimbabwe since its independence from Britain 1980. With its secure footholds, the ZANU-PF experienced no real political opposition until twenty years after its conception by the MDC. The 2000 elections, which the ZANU-PF eventually won, are considered by many international critiques to be neither free nor fair. Forty-eight days after the general election, Operation Murambatsvina was implemented. The government gave the following “justification for the operation: arresting disorderly or chaotic urbanization, including its health consequences; stopping illegal, parallel market transactions, especially foreign currency dealing and hoarding of consumer commodities in short supply; and reversing environmental damage caused by inappropriate urban agricultural practices.” On the contrary, the people affected and targeted by the operation speak to other motives. Zimbabwe’s failing economy mixed with Operation Murambatsvina and its political roots resulted in a cocktail of human rights violations. Operation Murambatsvina In 2005 the government program known as Operation Murambatsvina (Drive out Trash) was implemented, causing the forced eviction of 700,000 people from urban areas across the country. Promising a better life, it demolished the slums in all major cities. The evictions are believed to be an attempt by the Zanu-PF to stem growing support for the MDC in the nearing elections. Those who have suffered the most and continue to suffer today are the youth. Although promised better housing and schooling, reports show that the poor who were evicted are now living in worse conditions than before. Six years after resettlement, the government has still failed to build schools for the thousands of children that were displaced. The forced evictions which caused most people to lose their jobs, rising inflation rates and lack of schools have made it nearly impossible for the displaced children to receive an education. As a result, makeshift schools have cropped up throughout the settlements, but with little to no funding and scarce resources a proper education is nowhere near to be found. Quality of Life The lack of education has had a significant impact on the quality of life of the evicted youth. A report released from Amnesty International in October of 2011 stated that the education of 222,000 children in primary and secondary schools were disrupted by the evictions. A situational analysis done by the UN shows that almost half of the children from 2005-2010 did not go on from primary to secondary school. Starving for a better education, thousands of children have had to resort to leaving their families behind and make the dangerous journey alone into South Africa. In addition to crossing the dangerous Limpopo river which separates Zimbabwe and Africa with its crocodiles, snakes and unpredictable currents, the children still face the threat of thieves and gangs in the lawless no-mans’-land between the river and electric fence which lines the South African boarder. A youth who made it across stated how he was attacked by a gang of armed thieves (rumored to be former Zimbabwean soldiers) called the Magomagoma who robbed him while threatening him with a knife between his legs. They then forced him to watch as other men captured by the gang were made to rape young girls. Even if they manage to make it across into South Africa the children, with no money and no shelter, sleep on the streets or on the floors of churches. These children, now illegal immigrants, earn a living in whatever way they can---some beg and others get involved with older teens who drink and sniff glue. Despite all of the dangers the few success stories that have emerged continue to generate flocks of children who make the harrowing trip. Xoliswa Sithole (a South-African film-maker) commented, “When I lived in Zimbabwe in my twenties, there were hardly any street children in Harare. Children are now not only living on the streets, they are giving birth on the streets. A second generation of street children is growing up.” Whether they stay or go, these “Forgotten Children” (as Sithole dubs them) have had their once bright futures snuffed out before their eyes. Gender Roles In terms of gender, the forced evictions have had a higher impact on the educational opportunities for girls in comparison to boys. The historical and cultural barriers that inhibit females from receiving an education have been heightened and added to by the effects of the evictions. Plan International comments that “sexual harassment and abuse by even school teachers and parents, cultural issues, lack of school fees, early marriage, parental commitments and early pregnancies are some of the contributing factors to the dropout by the girl child.” With the lack of an education, many of the girls have resorted to sex work in order to support themselves and their families. Others who wish to avoid sex work choose to get married early in order to have someone who can support them. The legal age of sexual consent in Zimbabwe is sixteen, for marriage it is eighteen for boys and sixteen for girls. However girls as young as thirteen have been reported to enter into sexual relationships with older men and get married in order to escape poverty.The option of sending children to schools located farther away has provided no relief. The trip itself is dangerous; several children have been hit by motor vehicles over the past six years. For girls in particular there is the threat of rape while making the trip and at school. In school, the children are bullied and ostracized by their peers because they come from the makeshift settlements. A recent study show that the effects heightened by the evictions, namely poverty and abuse, have caused an alarming dropout rate in female attendance at school. A third of Zimbabwean girls have stopped attending primary school and 65 percent have stopped attending secondary school. Without the opportunities provided by a higher education, young girls are limited to sexual and subversive roles. The evictions also caused those with HIV and AIDS to no longer have access to care, and more than 79,500 people over the age of fifteen have been displaced. With their lack of knowledge and sexual lifestyle, young girls have a higher risk of infection and more rapid progression of the disease. Rights The lack of education itself is considered a human rights violation under the international human rights law. The United Nations Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights states that education plays a “vital role” in promoting human rights and alleviating poverty and its effects. Education reduces the violation of other human rights such as child labor, health and discrimination. It also reduces societal issues such as early marriage, which often undermine human rights, and promotes more interaction in public affairs. Zimbabwe is required under various human rights treaties to provide education that is compulsory and available to all. Before Operation Murambatsvina, education was not free, compulsory or available to all but significant strides towards better education were being made. However after Operation Murambatsvina, this progress not only halted but has, and continues to, retrogress. Despite pressures from various organizations such as Amnesty International and promises from the government, no real progress has been made to date.Courtesy of Konstantinos Dafalias