MICROFINANCE AND GENDERED OUTCOMES IN BRAZIL

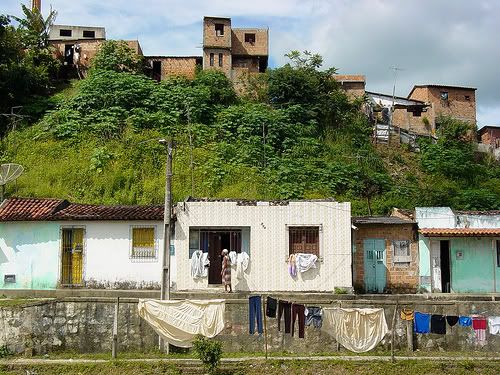

By Neda SaidContributing WriterThis paper will address the problematic implementation of microfinance programs in Brazil. Microfinance is often cited as a development strategy, but has a gendered impact that adversely affects women. Microfinance programs in Brazil lock women into the informal work sector and create persistent gendered discourse of perceived feminine qualities. Together, these elements have the effect of making women the targets of microfinance, while in reality hindering their empowerment. This paper will critique these policies using a critical gender analysis and offer recommendations to microfinance programs in Brazil to alleviate the adverse impacts on women and work towards real, effective development.I. Statement of IssueMicrofinance aims to expand access to financial services for people in impoverished areas that do not qualify for commercial financial services, with the goal of facilitating entrepreneurial efforts and increased wealth. Further, microfinance is said to empower women by increasing their bargaining power in the home, in the context of women having even less access to financial services then men do. Here empowerment will be defined as Laura Proaño (2005) suggests in her research – challenging patriarchal relations and redistributing power in a way that women gain greater equality with men (13). Women are empowered by the ability to have control over their own money and greater independence. Considering the application of microfinance services in Brazil however, a critical gendered analysis of its impact is far from complete. Although microfinance may increase access to financial services, the impact of such programs are not empowering to women, especially as many can become locked into informal labor and a gendered discourse that is detrimental to them.The phenomenon of globalization has brought about an increasingly integrated world. As a result, more attention has been brought to the global plight of poverty, and non-governmental organizations and other groups have been making an effort to initiate programs that deal with this global issue. Indeed, globalization has served as a catalyst to this process, with its consequences increasing the need for foreign intervention and aid. One aspect of this increased attention to international development is the implementation of microfinance programs in less developed countries where lack of access to funds and financial services is deemed a barrier to development and improvement of quality of life. This connection of microfinance to the adverse effects of globalization is especially evident in initiatives like the Millennium Development Goals. However, the situation of microfinance in Brazil is problematic and needs critical attention, as a development and gender empowerment strategy is producing the opposite of the desired outcome.This paper will demonstrate the gendered impact of microfinance and apply its findings to improving the effectiveness of microfinance programs in Brazil to work towards gender equity. The following section will address the history of microfinance in Brazil and provide a brief description of some of the programs in place. The third section will provide a critique and assessment of these policies in terms of its gendered impact. The fourth section will consist of recommendations for remedying policy concerning microfinance. Such recommendations will provide development organizations ways to take into account the gendered impact of microfinance in its implementation as a development strategy and address the sustained informality of labor and gendered discourse that has arisen. Ultimately, microfinance needs to be adapted with regional and gendered consideration in order for the possibility of gender empowerment to occur.II. Origin and History of ProblemSome essential facts about the implementation of microfinance in Brazil shed light on the roots of this problem of ineffectiveness. Brazil has experienced significant economic development in recent years, but is still known for having severe income inequality. Further, despite some positive trends, gender segregation remains a feature of the labor market. Kabeer (2003) suggests that the pay gap remains larger than can be explained by differences in skills or labor market segmentation, concluding there must be some degree of direct discrimination. In addition, there is insufficient access to financial services. There are significant spatial inequalities in bank branch presence in Brazil, as proven by Malamut (2006, 64), making clear that access to banking services is not by any means equal for all. Proaño (2005) explains that the poor have minimal access to financial institutions due to low-income jobs that are usually in the informal sector (9). This condition of informality serves as a barrier to accessing financial services, because the poor cannot qualify due to the informal nature of their employment and low-income status.Microfinance, which actually was first used in Brazil, is intended to alleviate this issue. Programs are highly concentrated in urban areas (Malamut 2006, 58), due to greater profitability and accessibility to clients. However, this also means that only certain people have access to these services. Further, microfinance programs have increasingly been counted on as a means of poverty alleviation and are especially geared towards women. Kabeer (2003) finds evidence for the positive impact of lending to women, using Brazilian data to indicate that unearned income in the hands of mothers had a far greater effect on family health than income in the hands of fathers. This data supporting the claim that money is better used when in the hands of women, partnered with the idea that microfinance empowers women, sustains a gendered discourse in the function of microfinance. This concept is commonly accepted as valid and thus used as reasoning to preferentially loan to women.In order to better understand how microfinance policy affects women in Brazil, it is imperative to examine how programs function on a more local level. Proaño (2005) found that half of the microfinance clients in Brazil in 2001 were at Banco do Nordeste, one of Brazil’s largest lending institutions (22). Malamut (2006) explains that Banco do Nordeste is a large state owned bank that initiated microfinance in the nineties and emphasizes the utilization of microfinance as an integrated and complementary instrument to public policies aimed at the promotion of local and regional development. An observation of the operation and impact of this institution is valuable in our exploration of microfinance and gender. Malamut (2006) states that almost half the clients at Banco do Nordeste are women (69). Most clients use Crediamigo, Brazil’s most prominent microfinance institution and also an initiative of Banco do Nordeste. CrediAmigo’s target market is urban microentrepreneurs. They are involved in small-scale manufacturing, commerce, and services, although the vast majority of clients are dedicated to such service activities as hairdressing and car repair, as Malamut found in his research of development models in Brazil (2006). The implications of Banco do Nordeste’s approach to finance as a result of these policy conditions will be discussed further in the critique.Another popular microfinance institution is Real Microcredito, which launched in the favelas, or slums, of São Paulo called Heliopolis in 2001. In this region, Malamut (2006) reveals there are 15.7 million people in informal economy, and 84 percent do not have access to credit (73). This is highly problematic in terms of access to banking, quality of life, and development prospects. Real Microcredito specializes in what are predominantly individual loans, 40 percent of which go to women (Malamut 2006, 74). The implications of this pattern in lending will be discussed further in the critique. Descriptions of both policies for Real Microcredito and Crediamigo do not provide a critical analysis of gender, only the important observation that women are more reliable borrowers.III. Critique of Existing PoliciesThese microfinance programs fail because they do not address any potential gendered impact on women. A critical analysis of how gender functions within these policies demonstrates how microfinance adversely affects women and fails to address the problem of empowering the female gender. Due to the preference to loan to women, a significant element in existing microfinance policy, these programs have the effect of persisting the informality of labor and the creation and persistence of gendered discourse that places greater burden on women. The impacts of this policy will be examined within the context of the specific microfinance programs that practice preferential loaning to women.Microfinance programs in Brazil tend to focus on women in the informal sector, which creates gendered dependence on these loans and their continued use. Often, these clients do not have access to any other financial services. Loans are received from institutions that do not offer savings accounts or other services, thus clients are only increasing their level of debt, as they have no method of saving. In addition, these clients are unable to enter more formal employment, as they take out loans to finance what are predominantly informal entrepreneurial or other labor endeavors with no prospect of real labor mobility into more formal employment.Real Microcredito has 95 percent of their clients in the informal sector, as confirmed by Malamut (2006, 73). As previously stated, many of these loans are individual ones that go to women. Individual loans, by nature, tend to place more stress on repayment than group loans. This element, Proaño (2005) argues, does not take into account the “triple role” of women, which is defined as reproductive work, productive work, and community managing (16). The additional stress of the loan adds to these other obligations, while only some are validated as real work. This same triple role of women also means that they are more likely to have jobs in the informal sector. Programs like Real Microcredito who have a majority of female clients in the informal sector increase women’s level of productive work without lessening the burden of any other obligation. As a result, women experience decreasing access to employment while becoming more dependent on informal work. In her examination of gender and financial access, Leila Bijos (2006) confirms this argument by stating that microfinance increases the informality of jobs, which adversely affects women more than men. The adverse impact is furthered by the lack of job security in the informal sector. Women are dependent on these loans although they hinder achieving labor mobility due to increasing debt. Consequently, such an element of policy offers few prospects for moving out of the informal sector.Microfinance policy reveals a preference to loan to women as a result of gendered discourse that says they handle money better. Proaño (2005) sums up this discourse in stating that women are targeted because of high rates of repayment and use of increased income to benefit the entire household (13). As suggested previously, the additional stress of loans in microfinance affects women more strongly than men in considering their triple role in society, as they still have the same amount of responsibility in other areas. These other essential roles of women are not considered time-consuming work, so the burden is not considered extra. Consequently, this gendered discourse leads to a gendered outcome creating a skewed idea of femininity – women are deemed more passive, reliable, and easier to work with. This can draw women into situations, like over borrowing, additional stress, and persisted informal work, that adversely affect their prospects for independence, much less empowerment. Along the same lines, Schonberger (2001) states that programs in Brazil are developing strategies to improve their outreach to potential women clients (18). It is evident that loans are preferentially given to women with no regard to the greater burdens on them. As a result, women are still subordinate to the patriarchal and masculine forces that control financial flows.Some examples make it clear that the gendered discourse behind microfinance is actually detrimental to women’s empowerment. While all of the Brazilian programs emphasized that they consider women clients to be easier to work with and more reliable in repayment, they indicated that in Brazilian society many women allow their husbands to sign for their loans. Here it is clear that women are not empowered by such processes. Another example of gendered discourse arises in Proaño’s (2005) proposed plan, which states that policy needs to ensure networks, access, and sustainability for women’s enterprises (23). This reveals a gendered idea of women and women’s labor – only certain forms of employment fall into the category of women’s enterprises, such as informal small business and services, like hairdressing. These are the kinds of enterprises women usually enter into, due to the very barriers of access that microfinance institutions are supposed to alleviate. Such policy recommendations continue to systematically lock women in to informal employment instead of working towards a method of labor mobility. Thus it is clear how gendered discourse is directly connected to women’s continuity in informal labor, and as demonstrated, the two often intersect.IV. Statement of Policy RecommendationsMicrofinance is a well-intentioned development strategy, but still does not solve a lot of problems. The poorest are still disadvantaged as they cannot qualify for loans or become locked in to informal labor. Further, women are even more adversely affected by the policy and gendered discourse that has developed about microfinance in Brazil. While such programs are intended to increase women’s control over funds, they end up placing greater stress upon their role in society, as they already have both productive and reproductive responsibilities (Littlefield et. al. 2003). Here, critical analysis of the gendered outcome of microfinance in Brazil will be implemented to suggest policy recommendations that take into consideration the adverse effects on women.First, microfinance does not adequately expand access to banking services. In the long term, commercial banks need to be more involved in supporting microfinance. I advise working with national banks instead of NGOs for microfinance efforts. If bank instability is still a significant complicating factor, certain attributes of these larger institutions could be implemented instead. Large state-run institutions can support more people and pool risk so that riskier ventures, analogous with loans for people with fewer qualifications, can be made. This way even the poorest could have increased access to financial services. Banks have a physical structure, a well-established information system, sound governance, available funds and established protocols for offering financial service (Malamut 2006, 79). Partnership with these institutions would strengthen the existing infrastructure, leading to true development. In order to support the rural poor, I propose that smaller NGOs partner with banks while still reaching out to these under-serviced areas. This way the strength gained from cooperation will not deter outreach to the impoverished.However, there is still the question of whether microfinance programs will continue to lock people – especially women – into debt and informal work. This problem points to the benefits of partnering with larger institutions like commercial banks: access to services beyond just lending. Women need other financial services such as savings accounts and training programs, to alleviate poverty and provide the chance of labor mobility. Of the microfinance institutions in Brazil, Proaño (2005) found, only commercial banks offer savings accounts (22). Thus increased partnership with such banks would provide more than just lending; these other aspects of financial services are necessary to see change in labor prospects for women. The public sector must invest in operations to alleviate the poverty of the poorest households in remote areas since sustainable microfinance institutions will not be able to fulfill this role (Malamut 2006, 80). Smaller NGOs are simply unable to fulfill all of these needs on their own, especially as they attempt to help the most marginalized populations. However, without targeting by gender, partnership with large banks would expand services and also the number of people they can reach. Obviously this will present challenges and require some initial strengthening of infrastructure, but will result in more sustainable development in the long run.The problem of gendered discourse remains an issue within microfinance. There must be greater consideration of the multiple labor roles of women in lending, as well as greater focus on gendered impacts. There is very little research done on the issue of gender and microfinance in Brazil. I propose that a research team provide comprehensive assessment of the role of women, how they use these programs, and how such programs may have a gendered impact that goes deeper than the discussion here. Finding specific issues with individual programs will allow for more refined improvement of microfinance institutions to achieve true gender empowerment. Proaño (2005) found that many microfinance institutions in Brazil indeed do not focus on gender (24), which presents the problematic action of preferring to loan to women without focus on how gender plays a role in microfinance. In addition, Brazil is very racially diverse with some of the worst income inequalities in the world, which differ by region (Proaño 2005, 27), adding to the dire need of more critical research in this area. There is great complexity in localized gender relations in Brazil, as well as intersectionality of gender, class, and race. This complexity is not addressed in the approach of the current microfinance institutions in Brazil, particularly in the interplay of gender. Again, there must be more research conducted to achieve greater critical understanding of how gender plays a role in the impact of microfinance.Instead of gendered discourse that dictates women are better clients due to overly feminized attributes, the triple role of women’s work needs to be fully considered in the implementation of microfinance. One such example is the increased stress that loans place on women, which is addressed by Crediamigo via group lending. Proaño (2005) explains how people understand the need for five people to qualify for a loan; contrary to solidarity lending, group lending requires not co-signers but trusting relationships and peer pressure for repayment (21). This system would disencumber women from relying on their husbands as co-signers. Additionally, participating in a group results in less pressure in terms of repayment through distributing the responsibility. Arguably, group lending is a better system for women as it offers greater flexibility, reduces the pressure of repayment, and does not target them for debt. In her study, Proaño (2005) determines that flexible loans, gender sensitive staff, and independence with how clients handled their money leads to empowerment (59). These aspects of microfinance institutions could be integrated into policy to increase prospects for gender empowerment.V. ConclusionMicrofinance programs in Brazil attempt to attain gender empowerment through increasing the availability of loans to women, but in effect result in a gendered outcome. This is overwhelmingly due to the structure of microfinance that locks women into the informal sector and creates a persistent gendered discourse. Critical gender analysis that observes microfinance’s effects on women in Brazil will help alleviate the adversity created by this issue. Ultimately, programs should implement microfinance as a temporary strategy. Micro-level loaning programs do not substitute for the real development of infrastructure that provides equal access or reaches out to the impoverished. Microfinance does not replace the necessary creation of infrastructure that a state needs to provide basic services for its citizens and a more effective means for the empowerment of women.Image by Flickr User Adam Jones, Ph.D., used under a Creative Commons License.Works CitedBijos, Leila. 2006. “Gender, Power, Financial Access, and Development in Latin America: Comparing Brazilian and Bolivian Cases.” Law and Business Review of the Americas.http://www.lexisnexis.com/hottopics/lnacademic/?csi=173459&shr=t&sr=AUTHOR(Bijos)+AND+TITLE (Gender%2C+Power%2C+Financial+Access%2C+and+Development+in+Latin+America%3A+Comparing+Brazilian+and+Bolivian+Cases)+AND+DATE+IS+2006 (11 May 2011).Kabeer, Nalia. 2003. “Gender Mainstreaming in Poverty Eradication and the Millennium Development Goals.” Gender Management System Series. International Development Research Centre. http://www.idrc.ca/openebooks/067-5. (20 April 2011).Littlefield, Elizabeth, Jonathan Murduch, and Syed Hashemi. 2003. “Is Microfinance an Effective Strategy to Reach the Millennium Development Goals?” Institute for Financial Management and Research. http://ifmr.ac.in/cmf/wp-content/uploads/2007/06/mf-mdgs-morduch.pdf. (21 April 2011).Malamut, Guilherme. 2006. “Microfinance in Bolivia, Bangladesh, and Brazil: Three Complementary Models.” Microfinance Developing Projects: 55-80.Proaño, Laura Lynn Fleischer. 2005. “Women’s Empowerment and Microcredit in Brazil: A Case Study of the Banco de Povo de Itabira.” Master’s Thesis. Ohio University.Schonberger, Steven N. 2001. “Microfinance Prospects in Brazil.” Sustainable Development Working Paper No. 12. http://mfbbva.org/uploads/tx_bbvagbmicrof/26pub_br101.pdf. (21 April 2011).

By Neda SaidContributing WriterThis paper will address the problematic implementation of microfinance programs in Brazil. Microfinance is often cited as a development strategy, but has a gendered impact that adversely affects women. Microfinance programs in Brazil lock women into the informal work sector and create persistent gendered discourse of perceived feminine qualities. Together, these elements have the effect of making women the targets of microfinance, while in reality hindering their empowerment. This paper will critique these policies using a critical gender analysis and offer recommendations to microfinance programs in Brazil to alleviate the adverse impacts on women and work towards real, effective development.I. Statement of IssueMicrofinance aims to expand access to financial services for people in impoverished areas that do not qualify for commercial financial services, with the goal of facilitating entrepreneurial efforts and increased wealth. Further, microfinance is said to empower women by increasing their bargaining power in the home, in the context of women having even less access to financial services then men do. Here empowerment will be defined as Laura Proaño (2005) suggests in her research – challenging patriarchal relations and redistributing power in a way that women gain greater equality with men (13). Women are empowered by the ability to have control over their own money and greater independence. Considering the application of microfinance services in Brazil however, a critical gendered analysis of its impact is far from complete. Although microfinance may increase access to financial services, the impact of such programs are not empowering to women, especially as many can become locked into informal labor and a gendered discourse that is detrimental to them.The phenomenon of globalization has brought about an increasingly integrated world. As a result, more attention has been brought to the global plight of poverty, and non-governmental organizations and other groups have been making an effort to initiate programs that deal with this global issue. Indeed, globalization has served as a catalyst to this process, with its consequences increasing the need for foreign intervention and aid. One aspect of this increased attention to international development is the implementation of microfinance programs in less developed countries where lack of access to funds and financial services is deemed a barrier to development and improvement of quality of life. This connection of microfinance to the adverse effects of globalization is especially evident in initiatives like the Millennium Development Goals. However, the situation of microfinance in Brazil is problematic and needs critical attention, as a development and gender empowerment strategy is producing the opposite of the desired outcome.This paper will demonstrate the gendered impact of microfinance and apply its findings to improving the effectiveness of microfinance programs in Brazil to work towards gender equity. The following section will address the history of microfinance in Brazil and provide a brief description of some of the programs in place. The third section will provide a critique and assessment of these policies in terms of its gendered impact. The fourth section will consist of recommendations for remedying policy concerning microfinance. Such recommendations will provide development organizations ways to take into account the gendered impact of microfinance in its implementation as a development strategy and address the sustained informality of labor and gendered discourse that has arisen. Ultimately, microfinance needs to be adapted with regional and gendered consideration in order for the possibility of gender empowerment to occur.II. Origin and History of ProblemSome essential facts about the implementation of microfinance in Brazil shed light on the roots of this problem of ineffectiveness. Brazil has experienced significant economic development in recent years, but is still known for having severe income inequality. Further, despite some positive trends, gender segregation remains a feature of the labor market. Kabeer (2003) suggests that the pay gap remains larger than can be explained by differences in skills or labor market segmentation, concluding there must be some degree of direct discrimination. In addition, there is insufficient access to financial services. There are significant spatial inequalities in bank branch presence in Brazil, as proven by Malamut (2006, 64), making clear that access to banking services is not by any means equal for all. Proaño (2005) explains that the poor have minimal access to financial institutions due to low-income jobs that are usually in the informal sector (9). This condition of informality serves as a barrier to accessing financial services, because the poor cannot qualify due to the informal nature of their employment and low-income status.Microfinance, which actually was first used in Brazil, is intended to alleviate this issue. Programs are highly concentrated in urban areas (Malamut 2006, 58), due to greater profitability and accessibility to clients. However, this also means that only certain people have access to these services. Further, microfinance programs have increasingly been counted on as a means of poverty alleviation and are especially geared towards women. Kabeer (2003) finds evidence for the positive impact of lending to women, using Brazilian data to indicate that unearned income in the hands of mothers had a far greater effect on family health than income in the hands of fathers. This data supporting the claim that money is better used when in the hands of women, partnered with the idea that microfinance empowers women, sustains a gendered discourse in the function of microfinance. This concept is commonly accepted as valid and thus used as reasoning to preferentially loan to women.In order to better understand how microfinance policy affects women in Brazil, it is imperative to examine how programs function on a more local level. Proaño (2005) found that half of the microfinance clients in Brazil in 2001 were at Banco do Nordeste, one of Brazil’s largest lending institutions (22). Malamut (2006) explains that Banco do Nordeste is a large state owned bank that initiated microfinance in the nineties and emphasizes the utilization of microfinance as an integrated and complementary instrument to public policies aimed at the promotion of local and regional development. An observation of the operation and impact of this institution is valuable in our exploration of microfinance and gender. Malamut (2006) states that almost half the clients at Banco do Nordeste are women (69). Most clients use Crediamigo, Brazil’s most prominent microfinance institution and also an initiative of Banco do Nordeste. CrediAmigo’s target market is urban microentrepreneurs. They are involved in small-scale manufacturing, commerce, and services, although the vast majority of clients are dedicated to such service activities as hairdressing and car repair, as Malamut found in his research of development models in Brazil (2006). The implications of Banco do Nordeste’s approach to finance as a result of these policy conditions will be discussed further in the critique.Another popular microfinance institution is Real Microcredito, which launched in the favelas, or slums, of São Paulo called Heliopolis in 2001. In this region, Malamut (2006) reveals there are 15.7 million people in informal economy, and 84 percent do not have access to credit (73). This is highly problematic in terms of access to banking, quality of life, and development prospects. Real Microcredito specializes in what are predominantly individual loans, 40 percent of which go to women (Malamut 2006, 74). The implications of this pattern in lending will be discussed further in the critique. Descriptions of both policies for Real Microcredito and Crediamigo do not provide a critical analysis of gender, only the important observation that women are more reliable borrowers.III. Critique of Existing PoliciesThese microfinance programs fail because they do not address any potential gendered impact on women. A critical analysis of how gender functions within these policies demonstrates how microfinance adversely affects women and fails to address the problem of empowering the female gender. Due to the preference to loan to women, a significant element in existing microfinance policy, these programs have the effect of persisting the informality of labor and the creation and persistence of gendered discourse that places greater burden on women. The impacts of this policy will be examined within the context of the specific microfinance programs that practice preferential loaning to women.Microfinance programs in Brazil tend to focus on women in the informal sector, which creates gendered dependence on these loans and their continued use. Often, these clients do not have access to any other financial services. Loans are received from institutions that do not offer savings accounts or other services, thus clients are only increasing their level of debt, as they have no method of saving. In addition, these clients are unable to enter more formal employment, as they take out loans to finance what are predominantly informal entrepreneurial or other labor endeavors with no prospect of real labor mobility into more formal employment.Real Microcredito has 95 percent of their clients in the informal sector, as confirmed by Malamut (2006, 73). As previously stated, many of these loans are individual ones that go to women. Individual loans, by nature, tend to place more stress on repayment than group loans. This element, Proaño (2005) argues, does not take into account the “triple role” of women, which is defined as reproductive work, productive work, and community managing (16). The additional stress of the loan adds to these other obligations, while only some are validated as real work. This same triple role of women also means that they are more likely to have jobs in the informal sector. Programs like Real Microcredito who have a majority of female clients in the informal sector increase women’s level of productive work without lessening the burden of any other obligation. As a result, women experience decreasing access to employment while becoming more dependent on informal work. In her examination of gender and financial access, Leila Bijos (2006) confirms this argument by stating that microfinance increases the informality of jobs, which adversely affects women more than men. The adverse impact is furthered by the lack of job security in the informal sector. Women are dependent on these loans although they hinder achieving labor mobility due to increasing debt. Consequently, such an element of policy offers few prospects for moving out of the informal sector.Microfinance policy reveals a preference to loan to women as a result of gendered discourse that says they handle money better. Proaño (2005) sums up this discourse in stating that women are targeted because of high rates of repayment and use of increased income to benefit the entire household (13). As suggested previously, the additional stress of loans in microfinance affects women more strongly than men in considering their triple role in society, as they still have the same amount of responsibility in other areas. These other essential roles of women are not considered time-consuming work, so the burden is not considered extra. Consequently, this gendered discourse leads to a gendered outcome creating a skewed idea of femininity – women are deemed more passive, reliable, and easier to work with. This can draw women into situations, like over borrowing, additional stress, and persisted informal work, that adversely affect their prospects for independence, much less empowerment. Along the same lines, Schonberger (2001) states that programs in Brazil are developing strategies to improve their outreach to potential women clients (18). It is evident that loans are preferentially given to women with no regard to the greater burdens on them. As a result, women are still subordinate to the patriarchal and masculine forces that control financial flows.Some examples make it clear that the gendered discourse behind microfinance is actually detrimental to women’s empowerment. While all of the Brazilian programs emphasized that they consider women clients to be easier to work with and more reliable in repayment, they indicated that in Brazilian society many women allow their husbands to sign for their loans. Here it is clear that women are not empowered by such processes. Another example of gendered discourse arises in Proaño’s (2005) proposed plan, which states that policy needs to ensure networks, access, and sustainability for women’s enterprises (23). This reveals a gendered idea of women and women’s labor – only certain forms of employment fall into the category of women’s enterprises, such as informal small business and services, like hairdressing. These are the kinds of enterprises women usually enter into, due to the very barriers of access that microfinance institutions are supposed to alleviate. Such policy recommendations continue to systematically lock women in to informal employment instead of working towards a method of labor mobility. Thus it is clear how gendered discourse is directly connected to women’s continuity in informal labor, and as demonstrated, the two often intersect.IV. Statement of Policy RecommendationsMicrofinance is a well-intentioned development strategy, but still does not solve a lot of problems. The poorest are still disadvantaged as they cannot qualify for loans or become locked in to informal labor. Further, women are even more adversely affected by the policy and gendered discourse that has developed about microfinance in Brazil. While such programs are intended to increase women’s control over funds, they end up placing greater stress upon their role in society, as they already have both productive and reproductive responsibilities (Littlefield et. al. 2003). Here, critical analysis of the gendered outcome of microfinance in Brazil will be implemented to suggest policy recommendations that take into consideration the adverse effects on women.First, microfinance does not adequately expand access to banking services. In the long term, commercial banks need to be more involved in supporting microfinance. I advise working with national banks instead of NGOs for microfinance efforts. If bank instability is still a significant complicating factor, certain attributes of these larger institutions could be implemented instead. Large state-run institutions can support more people and pool risk so that riskier ventures, analogous with loans for people with fewer qualifications, can be made. This way even the poorest could have increased access to financial services. Banks have a physical structure, a well-established information system, sound governance, available funds and established protocols for offering financial service (Malamut 2006, 79). Partnership with these institutions would strengthen the existing infrastructure, leading to true development. In order to support the rural poor, I propose that smaller NGOs partner with banks while still reaching out to these under-serviced areas. This way the strength gained from cooperation will not deter outreach to the impoverished.However, there is still the question of whether microfinance programs will continue to lock people – especially women – into debt and informal work. This problem points to the benefits of partnering with larger institutions like commercial banks: access to services beyond just lending. Women need other financial services such as savings accounts and training programs, to alleviate poverty and provide the chance of labor mobility. Of the microfinance institutions in Brazil, Proaño (2005) found, only commercial banks offer savings accounts (22). Thus increased partnership with such banks would provide more than just lending; these other aspects of financial services are necessary to see change in labor prospects for women. The public sector must invest in operations to alleviate the poverty of the poorest households in remote areas since sustainable microfinance institutions will not be able to fulfill this role (Malamut 2006, 80). Smaller NGOs are simply unable to fulfill all of these needs on their own, especially as they attempt to help the most marginalized populations. However, without targeting by gender, partnership with large banks would expand services and also the number of people they can reach. Obviously this will present challenges and require some initial strengthening of infrastructure, but will result in more sustainable development in the long run.The problem of gendered discourse remains an issue within microfinance. There must be greater consideration of the multiple labor roles of women in lending, as well as greater focus on gendered impacts. There is very little research done on the issue of gender and microfinance in Brazil. I propose that a research team provide comprehensive assessment of the role of women, how they use these programs, and how such programs may have a gendered impact that goes deeper than the discussion here. Finding specific issues with individual programs will allow for more refined improvement of microfinance institutions to achieve true gender empowerment. Proaño (2005) found that many microfinance institutions in Brazil indeed do not focus on gender (24), which presents the problematic action of preferring to loan to women without focus on how gender plays a role in microfinance. In addition, Brazil is very racially diverse with some of the worst income inequalities in the world, which differ by region (Proaño 2005, 27), adding to the dire need of more critical research in this area. There is great complexity in localized gender relations in Brazil, as well as intersectionality of gender, class, and race. This complexity is not addressed in the approach of the current microfinance institutions in Brazil, particularly in the interplay of gender. Again, there must be more research conducted to achieve greater critical understanding of how gender plays a role in the impact of microfinance.Instead of gendered discourse that dictates women are better clients due to overly feminized attributes, the triple role of women’s work needs to be fully considered in the implementation of microfinance. One such example is the increased stress that loans place on women, which is addressed by Crediamigo via group lending. Proaño (2005) explains how people understand the need for five people to qualify for a loan; contrary to solidarity lending, group lending requires not co-signers but trusting relationships and peer pressure for repayment (21). This system would disencumber women from relying on their husbands as co-signers. Additionally, participating in a group results in less pressure in terms of repayment through distributing the responsibility. Arguably, group lending is a better system for women as it offers greater flexibility, reduces the pressure of repayment, and does not target them for debt. In her study, Proaño (2005) determines that flexible loans, gender sensitive staff, and independence with how clients handled their money leads to empowerment (59). These aspects of microfinance institutions could be integrated into policy to increase prospects for gender empowerment.V. ConclusionMicrofinance programs in Brazil attempt to attain gender empowerment through increasing the availability of loans to women, but in effect result in a gendered outcome. This is overwhelmingly due to the structure of microfinance that locks women into the informal sector and creates a persistent gendered discourse. Critical gender analysis that observes microfinance’s effects on women in Brazil will help alleviate the adversity created by this issue. Ultimately, programs should implement microfinance as a temporary strategy. Micro-level loaning programs do not substitute for the real development of infrastructure that provides equal access or reaches out to the impoverished. Microfinance does not replace the necessary creation of infrastructure that a state needs to provide basic services for its citizens and a more effective means for the empowerment of women.Image by Flickr User Adam Jones, Ph.D., used under a Creative Commons License.Works CitedBijos, Leila. 2006. “Gender, Power, Financial Access, and Development in Latin America: Comparing Brazilian and Bolivian Cases.” Law and Business Review of the Americas.http://www.lexisnexis.com/hottopics/lnacademic/?csi=173459&shr=t&sr=AUTHOR(Bijos)+AND+TITLE (Gender%2C+Power%2C+Financial+Access%2C+and+Development+in+Latin+America%3A+Comparing+Brazilian+and+Bolivian+Cases)+AND+DATE+IS+2006 (11 May 2011).Kabeer, Nalia. 2003. “Gender Mainstreaming in Poverty Eradication and the Millennium Development Goals.” Gender Management System Series. International Development Research Centre. http://www.idrc.ca/openebooks/067-5. (20 April 2011).Littlefield, Elizabeth, Jonathan Murduch, and Syed Hashemi. 2003. “Is Microfinance an Effective Strategy to Reach the Millennium Development Goals?” Institute for Financial Management and Research. http://ifmr.ac.in/cmf/wp-content/uploads/2007/06/mf-mdgs-morduch.pdf. (21 April 2011).Malamut, Guilherme. 2006. “Microfinance in Bolivia, Bangladesh, and Brazil: Three Complementary Models.” Microfinance Developing Projects: 55-80.Proaño, Laura Lynn Fleischer. 2005. “Women’s Empowerment and Microcredit in Brazil: A Case Study of the Banco de Povo de Itabira.” Master’s Thesis. Ohio University.Schonberger, Steven N. 2001. “Microfinance Prospects in Brazil.” Sustainable Development Working Paper No. 12. http://mfbbva.org/uploads/tx_bbvagbmicrof/26pub_br101.pdf. (21 April 2011).