IMPLICATIONS OF THE CANADIAN HEALTH CARE SYSTEM FOR THE U.S.

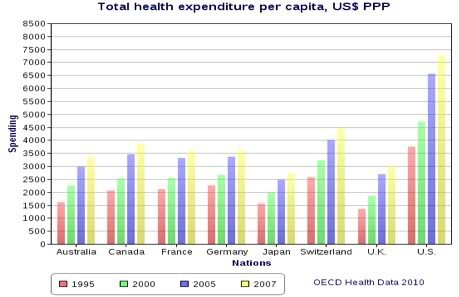

By Vidya MahavadiStaff WriterABSTRACTThis paper compares the returns to health-care in the United States to those in Canada. Methods of health-care payment in the United States are researched and examined alongside methods of health-care payment in Canada, leading to review of the quality of health-care system in each country respectively. Analysis of this three-way comparison (Quality-Quality, Cost-Cost, Quality-Cost) reveals that while costs are higher for Canada, there is not a significant increase in quality between the U.S.’s privatized health-care system and Canada’s nationalized one.INTRODUCTIONFor decades, the United States and the Canadian health-care systems have been compared to evaluate relative efficiency, costs, quality, and coverage. Canada has also often been promoted as the product of effective health-care reform, generating support for a “nationalized single payer system as an alternative to our [United States] mainly private multi-payer system” (O’Neill, June E. and O’Neill, Dave M., 2007).This comparison of the U.S. and Canadian health-care systems usually focuses on relative health-care expenditures and costs. The following graph taken from the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries shows that although expenditures per capita have risen for most of the first-world countries, U.S. health care expenditures per capita are still enormously greater than Canada’s – in 2007 expenditures were close to doubling Canada’s level (OECD Health Data 2010).

By Vidya MahavadiStaff WriterABSTRACTThis paper compares the returns to health-care in the United States to those in Canada. Methods of health-care payment in the United States are researched and examined alongside methods of health-care payment in Canada, leading to review of the quality of health-care system in each country respectively. Analysis of this three-way comparison (Quality-Quality, Cost-Cost, Quality-Cost) reveals that while costs are higher for Canada, there is not a significant increase in quality between the U.S.’s privatized health-care system and Canada’s nationalized one.INTRODUCTIONFor decades, the United States and the Canadian health-care systems have been compared to evaluate relative efficiency, costs, quality, and coverage. Canada has also often been promoted as the product of effective health-care reform, generating support for a “nationalized single payer system as an alternative to our [United States] mainly private multi-payer system” (O’Neill, June E. and O’Neill, Dave M., 2007).This comparison of the U.S. and Canadian health-care systems usually focuses on relative health-care expenditures and costs. The following graph taken from the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries shows that although expenditures per capita have risen for most of the first-world countries, U.S. health care expenditures per capita are still enormously greater than Canada’s – in 2007 expenditures were close to doubling Canada’s level (OECD Health Data 2010). This difference in health-care expenditure per capita is also reflected in the two countries’ dissimilarity in health-care expenditure of out-of-pocket payments (households) per capita, measured in US$ purchasing power parity (PPP). According to OECD statistics collected through extensive questionnaires and surveys of individuals and governments, in 2009 U.S. households spent $976.2/capita on health-care expenditures, while Canadian households spent only $635.6/capita (OECD Health Data 2010).With regards to quality, although Canada is known to have extremely high wait times in comparison to the U.S., the coverage and quality of health-care in Canada is more extensive. All Canadians are covered as are all health related issues and services, except for dental services and certain pharmaceutical drugs not covered by the publicly funded health insurance. Beyond this, however, not much research is available evaluating the quality of Canada’s health-care system.The goal of this paper is to examine the health-care costs per capita in both the U.S. and Canada and observe the relationship between the total amounts of health-care costs borne by households and the quality of health-care provided by each country.METHODS OF PAYMENTUNITED STATESU.S. health-care expenditures are funded by a variety of methods, including out-of-pocket payments, individual private insurance, employment-based private insurance, and government financing. A brief explanation will illuminate essential components of the system. First, out-of-pocket payment is the most straight-forward method that encompasses the direct purchase of goods and services by the consumer. Individual private insurance adds a third-party, the health insurer, to the payment scheme where the consumer is asked to pay the insurer who, in turn, reimburses the health-care provider. As a part of private health insurance, consumers also bear health-care costs in the form of premiums, co-payments, and deductibles. Premiums are the payments made by consumers simply to be enrolled under their respective private insurer, while a deductible refers to the out-of-pocket payment made by the consumer before the health insurer pays for its share. The co-payment is slightly different and refers to the out-of-pocket payment made by the consumer for any received health-care services before the health insurer pays for the rest of the service. Aside from individual private insurance, there is also employment-based private insurance in which the employer pays most of the premium that allows employees to have health insurance. Lastly, government financing represents the public health-care programs that provide care particularly to under-provided segments of the population. The two main government financed health-care programs are Medicare and Medicaid, which ensure care provision to the elderly and poor respectively (Bodenheimer, Grumbach).The distribution of the sources of health-care coverage is also important to understanding the totally costs borne by consumers of health-care. A breakdown of the sources of health-care coverage in the U.S. in 2009 shows that there are around 50.6 million uninsured Americans with the greatest source of health-care coverage coming from employment-based private insurance – 169.7 million people are insured through employers. Due to the fact that employer premium payments are tax-deductible or, in other words, the government does not treat the health insurance benefits as taxable income to the employee, the government gives up approximately $250 billion per year in tax revenues (Gruber, 2009).According to the recent Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA) that requires all U.S. residents to have health insurance, in order to make up for lost tax revenue of employment-based insurance, as well as improve coverage of most other areas of the U.S. health-care system, the government is using an increase in Medicare payroll tax of 0.9 percent and taxes to families and singles with an income greater than $250,000 and $200,000 per year, respectively. The government is also instating revised taxes on several sectors of the health-care system such as insurers, pharmaceutical companies, and medical device manufacturers that may benefit from the expanded coverage provided by the current health-care bill (Gruber, 2009). However, according to tabulations of U.S. National Income and Product Account Statistics and National Health Expenditure Accounts, although a significant number of consumers face health costs that take up a great percentage of their income, very small percentages (e.g. 14 percent in 2007) of personal health care is paid for by out-of-pocket consumer payments (Burtless and Svaton, 2010). Based on MEPS household survey data, costs of health-care actually have been rising, through higher premiums for the sick and health-care spending that have increased faster than consumption and household income (Burtless and Svaton, 2010), it is clear that out-of-pocket spending increases as adults age, with an increasing percentage of the household budget being used for health-care expenditures.CANADASince 1960, the Canadian health-care has been nationalized, meaning it’s a publicly funded health-care system paid primarily through private funds or generated tax revenues. As a result of providing all Canadians general tax-financed health-insurance, however, individuals and business in Canada are obligated to pay taxes between 3.0 percent and 4.7 percent of total tax revenues (Esmail, 2008). Statistics from the Canadian Institute for Health Information (CIHI) show that approximately $125 billion of Canadian tax dollars was spent on their nationalized health-care in 2010 (CIHI, 2010). The total tax revenue paid by individuals in Canada amounts to around $3,663 per Canadian (CIHI, 2010). The amount of taxes varies according to the number of children or dependents, but on average, an unattached individual earning around $36,962, pays a total tax bill of $14,472, nearly 40 percent of their total income (The Fraser Institute’s Canadian Tax Simulator, 2011). Aside from paying these high tax rates, Canadians are not billed for any insured service, which essentially includes all services except for certain pharmaceutical drugs and dental services (O’Neill, June E. and O’Neill, Dave M., 2007).Physicians are not allowed to charge any supplemental fees to patients and there are no unique prices or price differentiation between Canadian provinces, but they are however, allowed to charge patients for superior accommodation (OECD, 2010). There are also no premiums, deductibles or copayments imposed on Canadians (O’Neill, June E. and O’Neill, Dave M., 2007). In addition to no medical bills, the Canadian government controls the prices for all drugs that are not covered by the basic social coverage (OECD, 2010).From the cost descriptions provided above, it is clear that Canadians pay for their health insurance only through taxes, unless they require certain pharmaceutical drugs or dental services.ANALYSISThe rise in individual health-care costs in the U.S. can be attributed to the incessantly increasing U.S. health-care costs. Statistics in 2005 show for decades now, health-care costs have exceeded gross domestic product (GDP) growth by 2.5 percentage points on average and rose from 5.1 percent of GDP in 1960 to 16.5 percent of GDP in 2006 (Aaron and Meyer, 2005). Due to the rise of both government health-costs and individual health-costs, there have been an increasing number of individuals and families that, for lack of better choice, have been forced to remain uninsured. According to economic surveys taken between 2003 and 2007, the percentage of inadequately insured individuals rose from 35 percent to 42 percent, a number that has steadily risen due to rising unemployment due to the recession (Shoen, 2008). This fact adds to the research that shows that the U.S. health-care system expenditures per capita are almost twice as high as Canada’s (O’Neill, June E. and O’Neill, Dave M., 2007), which may have important implications for U.S. health-care policy.QUALITYUNITED STATESResearch on health-care payments projects a rather pessimistic future for the U.S. health-care system. Studies utilizing 2007 taxpayers data from the IRS show that in the future, the increasing financial strain will lead to immense increases in public taxes (Baicker and Skinner, 2011). These high costs of health-care should in effect translate into high quality of health-care, but studies show otherwise. First, a paper studying the health-care workforce, estimated a shortage of approximately 2,787 full-time physicians for around 6,000 palliative medicine patients (Lupu, 2010). This estimate does not even include the lack of access to outpatient specialist-level palliative care (Meier, 2011). Second, the lack of health-care research leads to increasing financial burden by extending the need for physician services and thus propagates a never-ending cycle. Research and investment is needed specifically in health-care areas that take up the greatest amount of funds. Without investment do to research, preventative measures cannot be taken, which consequently increases the prevalence of illnesses.A lack of research also leads to a lack of development of cures and treatments that will eventually lead to problems expanding beyond just individuals’ health. Aging individuals with abundant chronic conditions and functional impairments make up the majority of health-care spending (Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation et al. 2010), but research suggests that less than 0.01 percent of total National Institutes of Health (NIH) funding between 2003 and 2005 was for research pertaining to this area (Gelfman and Morrison, 2008). According to studies done in 2008, the U.S. health-care system has seen major problems regarding an increase in service demand without an increase in supply (Paulus, Davis, and Steele, 2008). Most notably, compared to the increases in individual health-care costs, only a 1.5 percent annual increase in the quality of health-care since 2000 was noted by the National Healthcare Quality Report (Agency for Health-care Research and Quality, 2007).CANADAIn general, the quality of Canadian health-care has not been disputed, but one of the largest problems with their publicly funded health-care system is that the waiting times are really high and there is a lack of sufficient non-acute care beds (OECD, 2010). Aside from those complaints, however, research shows that for the most part, the Canadian health-care system seems to be faring quite well and benefiting its citizens sufficiently. In Canada, patients are included in decisions regarding the coverage of health services (OECD, 2010). Again, as mentioned previously in the payment section of this paper, the Canadian government regulates the prices of all expenses needed to be borne by the individual outside of health-insurance. According to OECD statistics, as a result of this policy the satisfaction of many Canadians has risen (OECD, 2010).One very peculiar aspect of the Canadian health-care system, however, is that there is a very minute pool of resources available for evaluating the quality of the Canadian health-care system. This has hindered the evaluation of the quality of health-care based on self-reported status, however below some statistics are provided on Canada’s health-care quality in relation to U.S. quality evaluations, which may contribute to gaps in the quality analysis of Canada’s system.ANALYSISIt is clear that there are disparities between the coverage of health-care and the amount spent on health-care by the U.S. Although the U.S. spends nearly 17 percent of its GDP on health-care, coverage still does not include the entirety of the U.S. population and there remain approximately 50 million Americans that are uninsured. Analyzing the aspect of quality more closely, however, it is clear that individuals are not getting the attention and quality deserved relative to the cost and amount of money being paying to receive this care. The most frequently utilized measures of quality are life expectancy and infant mortality, and according to current hospital surveys, while the U.S. life expectancy for women and men is 80.1 years and 74.8 years, respectively, Canada exceeds these life expectancies by more than two years (O’Neill, June E. and O’Neill, Dave M., 2007). Infant mortality rates also reflect the superiority of the Canadian health-care system, with the infant death rate in deaths per 1000 live births being 5.3 in Canada, but 6.8 in the U.S. (O’Neill, June E. and O’Neill, Dave M., 2007). The Joint Canada/U.S. Survey of Health (JCUSH) conducted by surveying U.S. and Canadian residents, however, shows that the difference in self-reported health status was fairly small. Despite the Canadian health-system having lower incidence in all categories, the difference was relatively negligible.CONCLUSIONFrom the cost and quality analyses, it is clear that there is a huge gap between the individual costs of U.S. health-care as compared to Canadian health-care system, but reportedly not as huge a difference between the quality of care in the two countries. This result is troubling as it shows that even universal health coverage, which has been idealized for decades, may not be providing any more adequate care than a privatized health-care system. However, to make this conclusion more robust, comparisons of U.S. privatized healthcare to other universalized systems beyond Canada may prove helpful.What can be noted, however, is that although there is not a dramatically significant difference in the quality of care, at the least all Canadians are covered by their health-insurance, as opposed to the millions of Americans that go uninsured due to the extreme costs of health-care. Canadian’s paying 40 percent of the annual income should not be viewed as alarmingly high because in retrospect, everyone will be insured full covered for any future health problems that may arise. Most importantly, health-care is increasingly seen as a right that every human deserves such that no one should be left without the security of being taken care of in the event of illness. There remain barriers in the U.S. to fulfilling this right.One of the main problems in the U.S. is the immediate repulsion to a policy that raises taxes, even if citizens don’t fully comprehend and anticipate what benefits the tax may bring. On top of this fear, is worry of the U.S. becoming a progressively socialist country as universal health coverage grants the government full control over this sector of the country. As a result, citizens are not open to what could potentially benefit the welfare of the entire country.Thus the first step in moving towards a universal health-care plan or even a partially universal health-care plan, which tries to efficiently utilize both privatized and nationalized aspects of a health-care structure, is to change attitudes of the public. The main way to start gaining public support for a nationalized health-care plan is through educating the public of what are known as “spillover effects.” If the U.S. were to have nationalized health-care, all citizens would be covered and this could dramatically improve the health of all individuals. This improvement could translate into improved economic output due to a decrease in “sick-days”, in turn, improving the economical sector of the country. Alongside these attitude changes, it is necessary that the tax increases be implemented gradually, allowing U.S. citizens to digest the increasing costs and fully understand what the benefits of the increase are.Essentially, the core conclusion remains the same: the U.S. could greatly benefit from a nationalized health-care system, even if individuals pay significantly higher taxes. The reason being, that even if quality isn’t significantly different, it’s still marginally better in countries like Canada and moreover, everyone will be insured, reinstating the natural right that is health-care.Image by Flickr user ProgressOhio, used under a Creative Commons license.BIBLIOGRAPHYAaron, H. J., and J. Meyer. 2005. Health. In Restoring Fiscal Sanity 2005: Meeting the Long Run Challenges, ed. A. M. Rivlin and I. Sawhill, 73 – 97. Washington, DC: Brookings Institution Press.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. (2007). 2007. National Healthcare Quality Report. Rockville, MD: Author.Baicker, Katherine, and Jonathan S. Skinner. "Health Care Spending Growth And The Future Of U.S. Tax Rates." Natl Bur Econ Res Bull Aging Health. (2011): n. page. Print.Bodenheimer, Thomas S., and Kevin Grumbach.Understanding Health Policy: A Clinical Approach. 5th. 2009. Print.Burtless, Gary, and Pavel Svaton. "Health Care, Health Insurance, and the Distribution of American Incomes." Forum for Health Economics & Policy. 13.1 (2010): n. page. Print.Canadian Institute for Health Information [CIHI] (2010).National Health Expenditure Trends, 1975-2010. Canadian Institute for Health Information.Esmail, Nadeem. "Medicare's Steep Price: An in-depth look at the hidden costs of health care." Fraser Forum. (2008): n. page. Print.Fraser Institute (2011). The Fraser Institute’s Canadian Tax Simulator, 2011. FraserInstitute.Gelfman, L.P., and R.S.Morrison. 2008. Research Funding for Palliative Medicine. Journal of Palliative Medicine 11:36–43.Gruber, Jonathan, and Helen Levy. "The Evolution of Medical Spending Risk." Journal of Economic Perspectives. 23.4 (2009): 25-48. Print.Lupu, D. 2010. Estimates of Current Hospice and Palliative Medicine PhysicianWorkforce Shortage. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management 40:899–911.Meier, Diane E. "Increased Access to Palliative Care and Hospice Services: Opportunities to Improve Value in Health Care." Milbank Quarterly. 89.3 (2011): 343-380. Print.Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, and The Lewin Group. 2010. Individuals Living in the Community with Chronic Conditions and Functional Limitations: A Closer Look.Washington, DC. Available at http://aspe.hhs.gov/daltcp/reports/2010/closerlook.pdf (accessed June 17, 2011).O'Neill, June E., and Dave M. O'Neill. "Health Status Care And Inequality: Canada Vs. The U.S.." NBER Frontiers in Health Policy Research Conference. (2007): n. page. Print.Paris, V., M. Devaux and L. Wei (2010), “Health Systems Institutional Characteristics: A Survey of 29 OECD Countries”, OECD Health Working Papers, No. 50, OECD Publishing. http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/5kmfxfq9qbnr-enPaulus, R. A., Davis, K., & Steele, G. D. (2008). Continuous innovation in health care: implications of the Geisinger experience. Health Affairs, 27(5), 1235–1245.Shoen, Cathy "How Many Are Underinsured? Trends Among U.S. Adults, 2003 and 2007 " Health Affairs, June 10,2008; "Insured but Poorly Protected; How Many Are Underinsured? U. S. Adults Trends, 2003 to 2007," Commonwealth Fund, June 10,2008 (commonwealthfund.org)

This difference in health-care expenditure per capita is also reflected in the two countries’ dissimilarity in health-care expenditure of out-of-pocket payments (households) per capita, measured in US$ purchasing power parity (PPP). According to OECD statistics collected through extensive questionnaires and surveys of individuals and governments, in 2009 U.S. households spent $976.2/capita on health-care expenditures, while Canadian households spent only $635.6/capita (OECD Health Data 2010).With regards to quality, although Canada is known to have extremely high wait times in comparison to the U.S., the coverage and quality of health-care in Canada is more extensive. All Canadians are covered as are all health related issues and services, except for dental services and certain pharmaceutical drugs not covered by the publicly funded health insurance. Beyond this, however, not much research is available evaluating the quality of Canada’s health-care system.The goal of this paper is to examine the health-care costs per capita in both the U.S. and Canada and observe the relationship between the total amounts of health-care costs borne by households and the quality of health-care provided by each country.METHODS OF PAYMENTUNITED STATESU.S. health-care expenditures are funded by a variety of methods, including out-of-pocket payments, individual private insurance, employment-based private insurance, and government financing. A brief explanation will illuminate essential components of the system. First, out-of-pocket payment is the most straight-forward method that encompasses the direct purchase of goods and services by the consumer. Individual private insurance adds a third-party, the health insurer, to the payment scheme where the consumer is asked to pay the insurer who, in turn, reimburses the health-care provider. As a part of private health insurance, consumers also bear health-care costs in the form of premiums, co-payments, and deductibles. Premiums are the payments made by consumers simply to be enrolled under their respective private insurer, while a deductible refers to the out-of-pocket payment made by the consumer before the health insurer pays for its share. The co-payment is slightly different and refers to the out-of-pocket payment made by the consumer for any received health-care services before the health insurer pays for the rest of the service. Aside from individual private insurance, there is also employment-based private insurance in which the employer pays most of the premium that allows employees to have health insurance. Lastly, government financing represents the public health-care programs that provide care particularly to under-provided segments of the population. The two main government financed health-care programs are Medicare and Medicaid, which ensure care provision to the elderly and poor respectively (Bodenheimer, Grumbach).The distribution of the sources of health-care coverage is also important to understanding the totally costs borne by consumers of health-care. A breakdown of the sources of health-care coverage in the U.S. in 2009 shows that there are around 50.6 million uninsured Americans with the greatest source of health-care coverage coming from employment-based private insurance – 169.7 million people are insured through employers. Due to the fact that employer premium payments are tax-deductible or, in other words, the government does not treat the health insurance benefits as taxable income to the employee, the government gives up approximately $250 billion per year in tax revenues (Gruber, 2009).According to the recent Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA) that requires all U.S. residents to have health insurance, in order to make up for lost tax revenue of employment-based insurance, as well as improve coverage of most other areas of the U.S. health-care system, the government is using an increase in Medicare payroll tax of 0.9 percent and taxes to families and singles with an income greater than $250,000 and $200,000 per year, respectively. The government is also instating revised taxes on several sectors of the health-care system such as insurers, pharmaceutical companies, and medical device manufacturers that may benefit from the expanded coverage provided by the current health-care bill (Gruber, 2009). However, according to tabulations of U.S. National Income and Product Account Statistics and National Health Expenditure Accounts, although a significant number of consumers face health costs that take up a great percentage of their income, very small percentages (e.g. 14 percent in 2007) of personal health care is paid for by out-of-pocket consumer payments (Burtless and Svaton, 2010). Based on MEPS household survey data, costs of health-care actually have been rising, through higher premiums for the sick and health-care spending that have increased faster than consumption and household income (Burtless and Svaton, 2010), it is clear that out-of-pocket spending increases as adults age, with an increasing percentage of the household budget being used for health-care expenditures.CANADASince 1960, the Canadian health-care has been nationalized, meaning it’s a publicly funded health-care system paid primarily through private funds or generated tax revenues. As a result of providing all Canadians general tax-financed health-insurance, however, individuals and business in Canada are obligated to pay taxes between 3.0 percent and 4.7 percent of total tax revenues (Esmail, 2008). Statistics from the Canadian Institute for Health Information (CIHI) show that approximately $125 billion of Canadian tax dollars was spent on their nationalized health-care in 2010 (CIHI, 2010). The total tax revenue paid by individuals in Canada amounts to around $3,663 per Canadian (CIHI, 2010). The amount of taxes varies according to the number of children or dependents, but on average, an unattached individual earning around $36,962, pays a total tax bill of $14,472, nearly 40 percent of their total income (The Fraser Institute’s Canadian Tax Simulator, 2011). Aside from paying these high tax rates, Canadians are not billed for any insured service, which essentially includes all services except for certain pharmaceutical drugs and dental services (O’Neill, June E. and O’Neill, Dave M., 2007).Physicians are not allowed to charge any supplemental fees to patients and there are no unique prices or price differentiation between Canadian provinces, but they are however, allowed to charge patients for superior accommodation (OECD, 2010). There are also no premiums, deductibles or copayments imposed on Canadians (O’Neill, June E. and O’Neill, Dave M., 2007). In addition to no medical bills, the Canadian government controls the prices for all drugs that are not covered by the basic social coverage (OECD, 2010).From the cost descriptions provided above, it is clear that Canadians pay for their health insurance only through taxes, unless they require certain pharmaceutical drugs or dental services.ANALYSISThe rise in individual health-care costs in the U.S. can be attributed to the incessantly increasing U.S. health-care costs. Statistics in 2005 show for decades now, health-care costs have exceeded gross domestic product (GDP) growth by 2.5 percentage points on average and rose from 5.1 percent of GDP in 1960 to 16.5 percent of GDP in 2006 (Aaron and Meyer, 2005). Due to the rise of both government health-costs and individual health-costs, there have been an increasing number of individuals and families that, for lack of better choice, have been forced to remain uninsured. According to economic surveys taken between 2003 and 2007, the percentage of inadequately insured individuals rose from 35 percent to 42 percent, a number that has steadily risen due to rising unemployment due to the recession (Shoen, 2008). This fact adds to the research that shows that the U.S. health-care system expenditures per capita are almost twice as high as Canada’s (O’Neill, June E. and O’Neill, Dave M., 2007), which may have important implications for U.S. health-care policy.QUALITYUNITED STATESResearch on health-care payments projects a rather pessimistic future for the U.S. health-care system. Studies utilizing 2007 taxpayers data from the IRS show that in the future, the increasing financial strain will lead to immense increases in public taxes (Baicker and Skinner, 2011). These high costs of health-care should in effect translate into high quality of health-care, but studies show otherwise. First, a paper studying the health-care workforce, estimated a shortage of approximately 2,787 full-time physicians for around 6,000 palliative medicine patients (Lupu, 2010). This estimate does not even include the lack of access to outpatient specialist-level palliative care (Meier, 2011). Second, the lack of health-care research leads to increasing financial burden by extending the need for physician services and thus propagates a never-ending cycle. Research and investment is needed specifically in health-care areas that take up the greatest amount of funds. Without investment do to research, preventative measures cannot be taken, which consequently increases the prevalence of illnesses.A lack of research also leads to a lack of development of cures and treatments that will eventually lead to problems expanding beyond just individuals’ health. Aging individuals with abundant chronic conditions and functional impairments make up the majority of health-care spending (Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation et al. 2010), but research suggests that less than 0.01 percent of total National Institutes of Health (NIH) funding between 2003 and 2005 was for research pertaining to this area (Gelfman and Morrison, 2008). According to studies done in 2008, the U.S. health-care system has seen major problems regarding an increase in service demand without an increase in supply (Paulus, Davis, and Steele, 2008). Most notably, compared to the increases in individual health-care costs, only a 1.5 percent annual increase in the quality of health-care since 2000 was noted by the National Healthcare Quality Report (Agency for Health-care Research and Quality, 2007).CANADAIn general, the quality of Canadian health-care has not been disputed, but one of the largest problems with their publicly funded health-care system is that the waiting times are really high and there is a lack of sufficient non-acute care beds (OECD, 2010). Aside from those complaints, however, research shows that for the most part, the Canadian health-care system seems to be faring quite well and benefiting its citizens sufficiently. In Canada, patients are included in decisions regarding the coverage of health services (OECD, 2010). Again, as mentioned previously in the payment section of this paper, the Canadian government regulates the prices of all expenses needed to be borne by the individual outside of health-insurance. According to OECD statistics, as a result of this policy the satisfaction of many Canadians has risen (OECD, 2010).One very peculiar aspect of the Canadian health-care system, however, is that there is a very minute pool of resources available for evaluating the quality of the Canadian health-care system. This has hindered the evaluation of the quality of health-care based on self-reported status, however below some statistics are provided on Canada’s health-care quality in relation to U.S. quality evaluations, which may contribute to gaps in the quality analysis of Canada’s system.ANALYSISIt is clear that there are disparities between the coverage of health-care and the amount spent on health-care by the U.S. Although the U.S. spends nearly 17 percent of its GDP on health-care, coverage still does not include the entirety of the U.S. population and there remain approximately 50 million Americans that are uninsured. Analyzing the aspect of quality more closely, however, it is clear that individuals are not getting the attention and quality deserved relative to the cost and amount of money being paying to receive this care. The most frequently utilized measures of quality are life expectancy and infant mortality, and according to current hospital surveys, while the U.S. life expectancy for women and men is 80.1 years and 74.8 years, respectively, Canada exceeds these life expectancies by more than two years (O’Neill, June E. and O’Neill, Dave M., 2007). Infant mortality rates also reflect the superiority of the Canadian health-care system, with the infant death rate in deaths per 1000 live births being 5.3 in Canada, but 6.8 in the U.S. (O’Neill, June E. and O’Neill, Dave M., 2007). The Joint Canada/U.S. Survey of Health (JCUSH) conducted by surveying U.S. and Canadian residents, however, shows that the difference in self-reported health status was fairly small. Despite the Canadian health-system having lower incidence in all categories, the difference was relatively negligible.CONCLUSIONFrom the cost and quality analyses, it is clear that there is a huge gap between the individual costs of U.S. health-care as compared to Canadian health-care system, but reportedly not as huge a difference between the quality of care in the two countries. This result is troubling as it shows that even universal health coverage, which has been idealized for decades, may not be providing any more adequate care than a privatized health-care system. However, to make this conclusion more robust, comparisons of U.S. privatized healthcare to other universalized systems beyond Canada may prove helpful.What can be noted, however, is that although there is not a dramatically significant difference in the quality of care, at the least all Canadians are covered by their health-insurance, as opposed to the millions of Americans that go uninsured due to the extreme costs of health-care. Canadian’s paying 40 percent of the annual income should not be viewed as alarmingly high because in retrospect, everyone will be insured full covered for any future health problems that may arise. Most importantly, health-care is increasingly seen as a right that every human deserves such that no one should be left without the security of being taken care of in the event of illness. There remain barriers in the U.S. to fulfilling this right.One of the main problems in the U.S. is the immediate repulsion to a policy that raises taxes, even if citizens don’t fully comprehend and anticipate what benefits the tax may bring. On top of this fear, is worry of the U.S. becoming a progressively socialist country as universal health coverage grants the government full control over this sector of the country. As a result, citizens are not open to what could potentially benefit the welfare of the entire country.Thus the first step in moving towards a universal health-care plan or even a partially universal health-care plan, which tries to efficiently utilize both privatized and nationalized aspects of a health-care structure, is to change attitudes of the public. The main way to start gaining public support for a nationalized health-care plan is through educating the public of what are known as “spillover effects.” If the U.S. were to have nationalized health-care, all citizens would be covered and this could dramatically improve the health of all individuals. This improvement could translate into improved economic output due to a decrease in “sick-days”, in turn, improving the economical sector of the country. Alongside these attitude changes, it is necessary that the tax increases be implemented gradually, allowing U.S. citizens to digest the increasing costs and fully understand what the benefits of the increase are.Essentially, the core conclusion remains the same: the U.S. could greatly benefit from a nationalized health-care system, even if individuals pay significantly higher taxes. The reason being, that even if quality isn’t significantly different, it’s still marginally better in countries like Canada and moreover, everyone will be insured, reinstating the natural right that is health-care.Image by Flickr user ProgressOhio, used under a Creative Commons license.BIBLIOGRAPHYAaron, H. J., and J. Meyer. 2005. Health. In Restoring Fiscal Sanity 2005: Meeting the Long Run Challenges, ed. A. M. Rivlin and I. Sawhill, 73 – 97. Washington, DC: Brookings Institution Press.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. (2007). 2007. National Healthcare Quality Report. Rockville, MD: Author.Baicker, Katherine, and Jonathan S. Skinner. "Health Care Spending Growth And The Future Of U.S. Tax Rates." Natl Bur Econ Res Bull Aging Health. (2011): n. page. Print.Bodenheimer, Thomas S., and Kevin Grumbach.Understanding Health Policy: A Clinical Approach. 5th. 2009. Print.Burtless, Gary, and Pavel Svaton. "Health Care, Health Insurance, and the Distribution of American Incomes." Forum for Health Economics & Policy. 13.1 (2010): n. page. Print.Canadian Institute for Health Information [CIHI] (2010).National Health Expenditure Trends, 1975-2010. Canadian Institute for Health Information.Esmail, Nadeem. "Medicare's Steep Price: An in-depth look at the hidden costs of health care." Fraser Forum. (2008): n. page. Print.Fraser Institute (2011). The Fraser Institute’s Canadian Tax Simulator, 2011. FraserInstitute.Gelfman, L.P., and R.S.Morrison. 2008. Research Funding for Palliative Medicine. Journal of Palliative Medicine 11:36–43.Gruber, Jonathan, and Helen Levy. "The Evolution of Medical Spending Risk." Journal of Economic Perspectives. 23.4 (2009): 25-48. Print.Lupu, D. 2010. Estimates of Current Hospice and Palliative Medicine PhysicianWorkforce Shortage. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management 40:899–911.Meier, Diane E. "Increased Access to Palliative Care and Hospice Services: Opportunities to Improve Value in Health Care." Milbank Quarterly. 89.3 (2011): 343-380. Print.Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, and The Lewin Group. 2010. Individuals Living in the Community with Chronic Conditions and Functional Limitations: A Closer Look.Washington, DC. Available at http://aspe.hhs.gov/daltcp/reports/2010/closerlook.pdf (accessed June 17, 2011).O'Neill, June E., and Dave M. O'Neill. "Health Status Care And Inequality: Canada Vs. The U.S.." NBER Frontiers in Health Policy Research Conference. (2007): n. page. Print.Paris, V., M. Devaux and L. Wei (2010), “Health Systems Institutional Characteristics: A Survey of 29 OECD Countries”, OECD Health Working Papers, No. 50, OECD Publishing. http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/5kmfxfq9qbnr-enPaulus, R. A., Davis, K., & Steele, G. D. (2008). Continuous innovation in health care: implications of the Geisinger experience. Health Affairs, 27(5), 1235–1245.Shoen, Cathy "How Many Are Underinsured? Trends Among U.S. Adults, 2003 and 2007 " Health Affairs, June 10,2008; "Insured but Poorly Protected; How Many Are Underinsured? U. S. Adults Trends, 2003 to 2007," Commonwealth Fund, June 10,2008 (commonwealthfund.org)