THE EFFECTIVENES OF USAID IN FOSTERING LIBERALIZATION

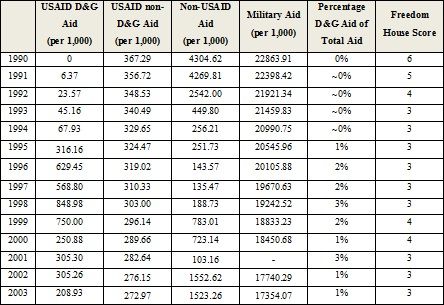

By Jodi Sanger-WeaverStaff WriterIn a previous article, it was argued that Algeria was an exemplary case of effective democracy and governance aid. Contrastingly, this article will compare data between Algeria and Egypt so as to make clear the differences that exist and allow for a clear understanding of why the Egyptian aid was not effective in fostering liberalization.Egypt began receiving USAID democracy and governance aid in 1991 at approximately US$6 per 1,000 people, slightly larger than the amount Algeria first began receiving in 1996 at just under US$3 per 1,000 people. In 1992 the amount of democracy and governance aid increased dramatically, surpassing the highest amount that Algeria received between 1990 and 2003, and continued to grow until it peaked in 1998 at approximately US$849 per 1,000 people. However, it wasn’t until 1995 that the democracy and governance aid was even comparable in percentages to military aid, and even then it was only 1 percent of total United States aid to Egypt.

By Jodi Sanger-WeaverStaff WriterIn a previous article, it was argued that Algeria was an exemplary case of effective democracy and governance aid. Contrastingly, this article will compare data between Algeria and Egypt so as to make clear the differences that exist and allow for a clear understanding of why the Egyptian aid was not effective in fostering liberalization.Egypt began receiving USAID democracy and governance aid in 1991 at approximately US$6 per 1,000 people, slightly larger than the amount Algeria first began receiving in 1996 at just under US$3 per 1,000 people. In 1992 the amount of democracy and governance aid increased dramatically, surpassing the highest amount that Algeria received between 1990 and 2003, and continued to grow until it peaked in 1998 at approximately US$849 per 1,000 people. However, it wasn’t until 1995 that the democracy and governance aid was even comparable in percentages to military aid, and even then it was only 1 percent of total United States aid to Egypt. *data collected from Cross-National Time-Series dataset (Banks 2005), Cross-National Research on USAID’s Democracy and Governance Programs dataset (Finkel et. al. 2007), US Census Bureau Statistical Abstracts (US Department of Commerce 1992-2005), and Historical Statistics of the World Economy dataset (Maddison 2006).The first four years that Egypt received democracy and governance aid, the Freedom House score dropped by a total of two points from a five to a four in 1992 and a four to a three in 1993. During these years, the percentage of democracy and governance aid was barely over 0 percent of total United States aid. Military aid was very high during these years, ranging from US$22,398.42 per 1,000 people to US$20,990.75 per 1,000 people, while the peak of democracy and governance aid was US$67.93 per 1,000 people. During this time, the Mubarak regime was being strengthened by the United States as the United States rewarded Egypt for supporting its interests in the Persian Gulf War. Even though the United States began giving democracy and governance aid during this time, the purpose of that aid was being clouded by the United States’ main goal in consolidating influence in Egyptian affairs in its attempt to cultivate a partnership in the region.The per capita democracy and governance aid as well as the percentage of democracy and governance aid peaked in 1998 at US$848.98 per 1,000 people and 3 percent respectively. Military aid had also been declining since 1990; however, it was still a significantly greater amount than the democracy and governance aid at US$19.242.52 per 1,000 people in 1998. Aid funneled to Egypt outside of USAID had significantly decreased since 1990, from US$4304.62 per 1,000 people to US$188.73 per 1,000 people in 1998. The significant increase in democracy and governance aid and the significant decrease in aid outside of USAID combined with the slight decrease in military aid likely had an effect on the Freedom House score's one point improvement between 1998 and 1999 from three to four. Consequently, in 1999 and 2000 aid outside of USAID spiked once again and the democracy and governance aid declined dramatically, and in 2001 the Freedom House score once again dropped one point back to a three. The Freedom House score remained at a three through 2003, likely as a result of the United States shifting interests after the September 11th attacks back to securing stability in Egypt instead of promoting democracy.Apparent in the data, the military rule in Egypt was strengthened by the extensive United States military aid. Nasser, Sadat and Mubarak were all members of the military and used it to retain power. Through the military they were able to resist democratization, an objective that was in essence strengthened by the United States. The military was also more than just a combat force. It produced consumer goods as well and operated under no budgetary accountability (Deeb 2011, 407). Because of this, the army was able to monopolize many segments of the Egyptian economy and extend its control over the country. Not only could the army physically combat dissidents, it also held the economic upper hand. United States efforts to promote democracy in Egypt were undermined and rendered futile by its own hand. By providing Egypt with military aid in its quest to promote stability in the country for its own national interests, the United States undermined the capacity of the Egyptian people to lobby for liberalization. The USAID democracy and governance funds Egypt received were wasted against a military regime propped up by United States military aid. The promotion of democracy and good governance was nominal at best.The United States own national interests in the region surely clouded the ability of the democracy and governance aid to be effective in causing liberalization. The desires for regional stability, peace in Israel, and leverage against Iran have all affected the United States’ relationship with Egypt. Because of the United States’ own interests, it has been willing to praise the “liberalization” of the Egyptian regime and demonize the “oppressive” regime in Iran, even though the two regimes are not dissimilar in their respective levels of freedom according to the Freedom House measures. In 2005, in a speech at the American University in Cairo, Condoleezza Rice admitted that "for 60 years, my country, the United States, pursued stability at the expense of democracy in this region here in the Middle East, and we achieved neither,” and posed that the United States was now “taking a different course. We are supporting the democratic aspirations of all people” (Weisman 2005). However, she still refused to meet with the Muslim Brotherhood even though it was considered at the time to be the most popular political organization in the country (a thought affirmed by the recent 2011 parliamentary elections in Egypt). Her reason was respect for the laws of Egypt, even though those laws were undemocratic, a decision in essence hypocritical of her declaration to support the democratic aspirations of Egyptians.Rice further propped up the undemocratic regime of Egypt when she admonished Iran, stating that “the appearance of elections does not mask the organized cruelty of Iran’s theocratic state,” while at the same time praising the Mubarak regime for its nominal steps toward liberalization even though the Iranian elections were more free and fair than Egypt’s own elections were expected to be (Weisman 2005). The fact that Rice, representing American governmental attitudes, continued to praise the authoritarian military regime in Egypt was indicative that, although democracy and governance aid may increase, support for the regime was not likely to decrease. Because of this, as made clear by the statistics, the democracy and governance aid had little hope of making a difference in the liberalization of the country.Although looking at the raw numbers of democracy and governance aid to Egypt compared to the democracy and governance aid to Algeria may lead one to believe that Egypt should be more successful, it is apparent that there were too many other factors at play in Egypt in order to make liberalization successful. While it may have been an interest of the United States to increase liberalization in Egypt, it was more important to maintain a cooperative relationship with the undemocratic Egyptian regime. Therefore, any attempts to aid in the liberalization of the country were distracted by the grand scheme of the relationship between the two countries. Not only do the statistics suggest that lower percentages of democracy and governance aid lead to lower chances of liberalization, they also suggest that military aid decreases the likelihood of liberalization as well. Egypt exhibited low democracy and governance percentages and very high military aid, lending a valid explanation to why the high raw numbers of democracy and governance aid were not effective in liberalizing the country. References:Banks, Arthur S. 2005. Cross-National Time Series, 1815-2003. Data Archive.Binghamton, NY: Databanks International.Deeb, Marius. “Arabic Republic of Egypt.” The Government and Politics of the Middle East and North Africa, Sixth Edition. Ed. David E. Long, Bernard Reich, and Mark Gasiorowski. Boulder: Westview Press, 2011. 397-421. Print.Finkel, Steven, Andrew Green, Aníbal Pérez-Liñán, Mitchell Seligson, and C. Neal Tate. Cross-National Research on USAID’s Democracy and Governance Programs, Phase II. Pittsburgh, PA: University of Pittsburgh, 2007.Maddison, Angus. 2006. Historical Statistics of the World Economy: 1-2006 AD. University of Groningen.U.S. Department of Commerce. Bureau of the Census. 1992-2005. Statistical Abstract of the United States, Section 28: Foreign Aid and Commerce. Washington: Department of Commerce.Weisman, Steven R. “Rice Urges Egyptians and Saudis to Democratize.” The New York Times International 21 June 2005. Web. 7 Feb 2012.Photo by Chris Wieland *This article has been modified for clarity.

*data collected from Cross-National Time-Series dataset (Banks 2005), Cross-National Research on USAID’s Democracy and Governance Programs dataset (Finkel et. al. 2007), US Census Bureau Statistical Abstracts (US Department of Commerce 1992-2005), and Historical Statistics of the World Economy dataset (Maddison 2006).The first four years that Egypt received democracy and governance aid, the Freedom House score dropped by a total of two points from a five to a four in 1992 and a four to a three in 1993. During these years, the percentage of democracy and governance aid was barely over 0 percent of total United States aid. Military aid was very high during these years, ranging from US$22,398.42 per 1,000 people to US$20,990.75 per 1,000 people, while the peak of democracy and governance aid was US$67.93 per 1,000 people. During this time, the Mubarak regime was being strengthened by the United States as the United States rewarded Egypt for supporting its interests in the Persian Gulf War. Even though the United States began giving democracy and governance aid during this time, the purpose of that aid was being clouded by the United States’ main goal in consolidating influence in Egyptian affairs in its attempt to cultivate a partnership in the region.The per capita democracy and governance aid as well as the percentage of democracy and governance aid peaked in 1998 at US$848.98 per 1,000 people and 3 percent respectively. Military aid had also been declining since 1990; however, it was still a significantly greater amount than the democracy and governance aid at US$19.242.52 per 1,000 people in 1998. Aid funneled to Egypt outside of USAID had significantly decreased since 1990, from US$4304.62 per 1,000 people to US$188.73 per 1,000 people in 1998. The significant increase in democracy and governance aid and the significant decrease in aid outside of USAID combined with the slight decrease in military aid likely had an effect on the Freedom House score's one point improvement between 1998 and 1999 from three to four. Consequently, in 1999 and 2000 aid outside of USAID spiked once again and the democracy and governance aid declined dramatically, and in 2001 the Freedom House score once again dropped one point back to a three. The Freedom House score remained at a three through 2003, likely as a result of the United States shifting interests after the September 11th attacks back to securing stability in Egypt instead of promoting democracy.Apparent in the data, the military rule in Egypt was strengthened by the extensive United States military aid. Nasser, Sadat and Mubarak were all members of the military and used it to retain power. Through the military they were able to resist democratization, an objective that was in essence strengthened by the United States. The military was also more than just a combat force. It produced consumer goods as well and operated under no budgetary accountability (Deeb 2011, 407). Because of this, the army was able to monopolize many segments of the Egyptian economy and extend its control over the country. Not only could the army physically combat dissidents, it also held the economic upper hand. United States efforts to promote democracy in Egypt were undermined and rendered futile by its own hand. By providing Egypt with military aid in its quest to promote stability in the country for its own national interests, the United States undermined the capacity of the Egyptian people to lobby for liberalization. The USAID democracy and governance funds Egypt received were wasted against a military regime propped up by United States military aid. The promotion of democracy and good governance was nominal at best.The United States own national interests in the region surely clouded the ability of the democracy and governance aid to be effective in causing liberalization. The desires for regional stability, peace in Israel, and leverage against Iran have all affected the United States’ relationship with Egypt. Because of the United States’ own interests, it has been willing to praise the “liberalization” of the Egyptian regime and demonize the “oppressive” regime in Iran, even though the two regimes are not dissimilar in their respective levels of freedom according to the Freedom House measures. In 2005, in a speech at the American University in Cairo, Condoleezza Rice admitted that "for 60 years, my country, the United States, pursued stability at the expense of democracy in this region here in the Middle East, and we achieved neither,” and posed that the United States was now “taking a different course. We are supporting the democratic aspirations of all people” (Weisman 2005). However, she still refused to meet with the Muslim Brotherhood even though it was considered at the time to be the most popular political organization in the country (a thought affirmed by the recent 2011 parliamentary elections in Egypt). Her reason was respect for the laws of Egypt, even though those laws were undemocratic, a decision in essence hypocritical of her declaration to support the democratic aspirations of Egyptians.Rice further propped up the undemocratic regime of Egypt when she admonished Iran, stating that “the appearance of elections does not mask the organized cruelty of Iran’s theocratic state,” while at the same time praising the Mubarak regime for its nominal steps toward liberalization even though the Iranian elections were more free and fair than Egypt’s own elections were expected to be (Weisman 2005). The fact that Rice, representing American governmental attitudes, continued to praise the authoritarian military regime in Egypt was indicative that, although democracy and governance aid may increase, support for the regime was not likely to decrease. Because of this, as made clear by the statistics, the democracy and governance aid had little hope of making a difference in the liberalization of the country.Although looking at the raw numbers of democracy and governance aid to Egypt compared to the democracy and governance aid to Algeria may lead one to believe that Egypt should be more successful, it is apparent that there were too many other factors at play in Egypt in order to make liberalization successful. While it may have been an interest of the United States to increase liberalization in Egypt, it was more important to maintain a cooperative relationship with the undemocratic Egyptian regime. Therefore, any attempts to aid in the liberalization of the country were distracted by the grand scheme of the relationship between the two countries. Not only do the statistics suggest that lower percentages of democracy and governance aid lead to lower chances of liberalization, they also suggest that military aid decreases the likelihood of liberalization as well. Egypt exhibited low democracy and governance percentages and very high military aid, lending a valid explanation to why the high raw numbers of democracy and governance aid were not effective in liberalizing the country. References:Banks, Arthur S. 2005. Cross-National Time Series, 1815-2003. Data Archive.Binghamton, NY: Databanks International.Deeb, Marius. “Arabic Republic of Egypt.” The Government and Politics of the Middle East and North Africa, Sixth Edition. Ed. David E. Long, Bernard Reich, and Mark Gasiorowski. Boulder: Westview Press, 2011. 397-421. Print.Finkel, Steven, Andrew Green, Aníbal Pérez-Liñán, Mitchell Seligson, and C. Neal Tate. Cross-National Research on USAID’s Democracy and Governance Programs, Phase II. Pittsburgh, PA: University of Pittsburgh, 2007.Maddison, Angus. 2006. Historical Statistics of the World Economy: 1-2006 AD. University of Groningen.U.S. Department of Commerce. Bureau of the Census. 1992-2005. Statistical Abstract of the United States, Section 28: Foreign Aid and Commerce. Washington: Department of Commerce.Weisman, Steven R. “Rice Urges Egyptians and Saudis to Democratize.” The New York Times International 21 June 2005. Web. 7 Feb 2012.Photo by Chris Wieland *This article has been modified for clarity.