HUMOR: EGYPT'S REVOLUTIONARY ALLY

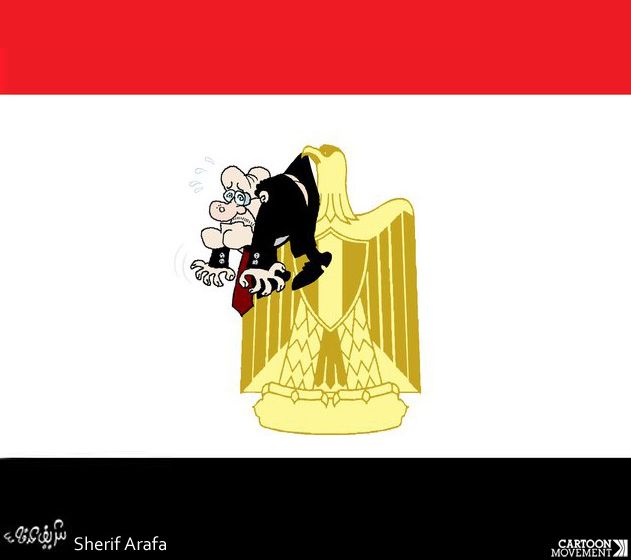

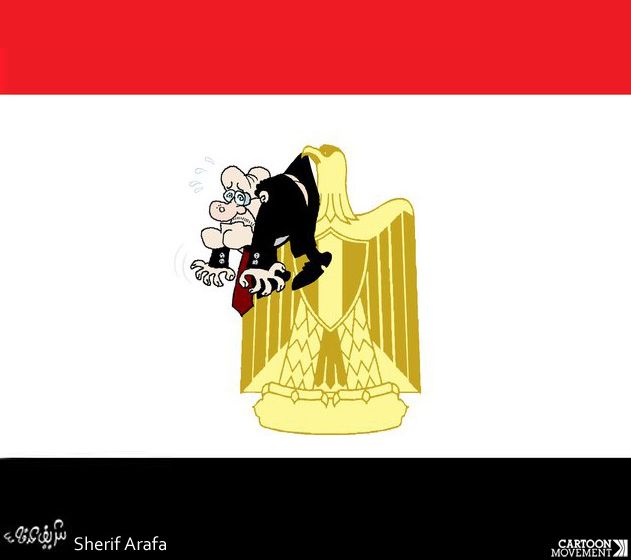

By Satenik HarutyunyanContributing WriterIn the last month, the Egyptian people voted to choose their new president. Although the country’s fate still remains uncertain, Egypt’s journey to electing its new leader began with a series of revolutions that shook the modern world. Whether titled the Arab Revolutions, the Arab Spring, or the Facebook Revolutions, this series of political and social uprisings took 2011 by storm and remains ever important as a new year unfolds. On a now historic day in December 2010, one young man’s controversial act of defiance in Tunisia served as the final catalyst for a succession of awe-inspiring political movements. These very political movements have since been the epicenter of political, social, and media discussion all over the planet. Due their complex, multifaceted, and unique nature, the Arab Revolutions provide scholars and intellectuals a plethora of sociological and political questions to demystify. Although bound by certain collective principles, each of the uprisings has a distinct identity with a specific set of contributing factors. Moreover, in order to fully grasp the scope of the Arab Spring, it is absolutely crucial to understand the particularities and distinct elements of each movement as they pertain to the uprisings as a whole.Humor and Egyptian Culture:Without contextualizing what humor has historically meant in Arab world and in Egyptian society, it is difficult to understand the importance of its role in the recent revolutions. Firstly, due to its rather ambiguous definition, it is critical to understand what the term “Arab World” encompasses. Geert Hofstede, an influential Dutch social psychologist and anthropologist, grouped Egypt, Iraq, Kuwait, Lebanon, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates together and titled them the “Arab World” based on five different cultural dimensions (Rohm 3). The modern day Arab World is bound together by numerous cultural and historic similarities and yet each nation within the group is distinct. Throughout the Arab World and especially in Egypt, humor has been a cornerstone element of society. The love Egyptians have for humor and joke-telling is well-known in the Arab world. In fact, there is a common phrase used by neighboring Arab populations to describe Egyptians, which literally translates to “son of the jokes” (ibn nukta) (Shehata 75).Humor is no new addition to Egyptian society. As a matter of fact, William Fry, an American sociologist, notes that the use of humor was present in Egyptian society as early as dynastic times. Indeed, ancient Egyptians were quite advanced in the use of literary devices such as satire. Patrick Houlihan explains that “the ancient Egyptians undoubtedly chuckled at writing that employed wit, satire, word-plays, irony, puns, and other sophisticated literary devices (Houlihan). ” In addition to literature, Houlihan also examines the use of visual humor in tomb-chapel decorations as well as in illustrations on papyri and figured ostraca.Here, it is important to note that the use of social satire in ancient Egyptian society was also linked to criticism of oppressive political figures. For example, a joke that dates back over 4,000 years mocks the pharaoh’s refusal to partake in the common man’s activities. Essentially, by stating that the only way to convince the pharaoh to fish is by placing naked girls in the fishing nets, this form of social humor represents a larger political message. The use of humor in Egyptian society continued to evolve as history wore on. After the age of dynasties and during Roman rule, Egyptian advocates were legally banned from practicing law because of a known tendency to employ wit and humor in their work. Romans found such behavior offensive to the serious nature of the profession.This historic and foundational use of humor has certainly had a major influence on the way humor manifests in Egypt’s contemporary society. Certain scholars such as Samer Shaheta argue that Egyptian social humor took on a new form after a group of military leaders called the Free Officers the corrupt monarchy of King Farouk and replaced it with a military regime (Shaheta 83). With the new regime came many modifications and Egyptians gained the right to organize political parties, as well as the rights to free speech and press. But, the military rulers who governed Egypt for the second half of the twentieth century (Nasser, Sadat, and Mubarak) still paid limited amounts of attention to human rights or the principle of democracy.Social humor, however, is unique in that it is able to thrive in an authoritarian society because it is in many cases difficult to censor. The government’s difficulty in censoring social satire and political jokes comes partially from an oral culture. Because such jokes are often told during informal setting through word of mouth, the government is unable to conduct thorough censorship. In Egypt, this kind of social humor has been referred to as “nukta”, which can be explained as a verbal cartoon. The “nukta” is a verbal exchange between people that serves as an oral editorial with critical value. All the same, any Egyptian “nukta” makes its statement through humorous means.Contemporary Egyptian society therefore finds itself in a situation where an age old tradition of joke telling, social injustice, and a limited amount of free speech all coexist. Accordingly, Egyptian political leaders and their regimes became the primary targets of political criticism in the form of jokes. With a deeply entrenched historical and contemporary tradition of incorporating humor into society, the Egyptian tendency to use these elements is only logical when it comes to the revolution of 2011. During the revolution, the Egyptian protesters and activists were able to take joke telling and humor, something with which they were already strongly familiar, to another level. In a way, the age old tradition of political and social humor took on an evolved form, reaching a new height during the Arab Spring.The Political Cartoon as an Accessory to Revolution:Today, it is difficult to imagine political humor without the existence of the political cartoon. Throughout the world, political cartoons are a humoristic approach to political and social commentary. At times they are laughter-invoking and at times, they depict the darkest aspects of political structures. But regardless of the message they convey, political cartoons are a unique part of political humor in the contemporary age and they certainly played an important role during the Arab Spring.The earliest pictorial cartoons can be traced to ancient Egypt. The bas-relief dating from 2000 BC is now kept at a museum in Cairo. Whereas pictorial cartoons may have first been seen in historic Egypt, the usage of political cartoons in Egypt is a much more recent development. Furthermore, circulating and publishing political cartoons has historically been a difficult task due to censorship and autocratic governing systems.In the last sixty years, however, political cartoons were placed into a grey area between being entirely censored and entirely permitted. This semi-censored type of cartoon became of utmost importance during the Arab Spring of 2011. Under Mubarak, although cartoonists did have the right to publish critical political cartoons, their freedoms were greatly limited by the government. These limitations forced political cartoonists to display their messages subliminally through indirect messages. Even during the uprisings, political cartoonists had to go through profound obstacles in order to send their humorous messages to the Egyptian people. Even during the protests and the buildup toward revolution, if a cartoonist wished to publish a political cartoon, he or she would not be allowed to draw a specific political figure. One contemporary political cartoonist from Egypt named Sherif Arafa explains his strategy to continue making political jokes in the face of government oppression. During Mubarak’s regime, the artist created a figure called “the Responsible” who represents the top political figures. Arafa says, “I draw him differently every time so he can have the physical characteristics and age of the top officials I want to criticize. My readers understand whom I mean by the context of the cartoon (Tomoe).” Until Mubarak stepped down in February, directly attacking the government through this form of social humor was extremely dangerous in Egypt. Cartoonists were often arrested, kidnapped, and tortured if they attempted to publish overtly critical political jokes. Even considering these risks, cartoonists such as Arafa strategically used this form of humor to relay their political messages as the revolution began to take form.Additionally, cartoonists were able to start publishing more overtly critical jokes after the president stepped down and his regime toppled. Below are two political cartoons published in Egyptian news sources. The cartoon on the left was published in January before the leader resigned while the cartoon on the right was published after Mubarak’s resignation and depicts a caricature that bears a much stronger resemblance to the former president. The second cartoon is clearly showing an Egypt full of light as the shadow of Mubarak is removed. Whereas the first cartoon is humorous and equally amusing, the second cartoon indicates that the revolution had a great impact in Egypt.

By Satenik HarutyunyanContributing WriterIn the last month, the Egyptian people voted to choose their new president. Although the country’s fate still remains uncertain, Egypt’s journey to electing its new leader began with a series of revolutions that shook the modern world. Whether titled the Arab Revolutions, the Arab Spring, or the Facebook Revolutions, this series of political and social uprisings took 2011 by storm and remains ever important as a new year unfolds. On a now historic day in December 2010, one young man’s controversial act of defiance in Tunisia served as the final catalyst for a succession of awe-inspiring political movements. These very political movements have since been the epicenter of political, social, and media discussion all over the planet. Due their complex, multifaceted, and unique nature, the Arab Revolutions provide scholars and intellectuals a plethora of sociological and political questions to demystify. Although bound by certain collective principles, each of the uprisings has a distinct identity with a specific set of contributing factors. Moreover, in order to fully grasp the scope of the Arab Spring, it is absolutely crucial to understand the particularities and distinct elements of each movement as they pertain to the uprisings as a whole.Humor and Egyptian Culture:Without contextualizing what humor has historically meant in Arab world and in Egyptian society, it is difficult to understand the importance of its role in the recent revolutions. Firstly, due to its rather ambiguous definition, it is critical to understand what the term “Arab World” encompasses. Geert Hofstede, an influential Dutch social psychologist and anthropologist, grouped Egypt, Iraq, Kuwait, Lebanon, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates together and titled them the “Arab World” based on five different cultural dimensions (Rohm 3). The modern day Arab World is bound together by numerous cultural and historic similarities and yet each nation within the group is distinct. Throughout the Arab World and especially in Egypt, humor has been a cornerstone element of society. The love Egyptians have for humor and joke-telling is well-known in the Arab world. In fact, there is a common phrase used by neighboring Arab populations to describe Egyptians, which literally translates to “son of the jokes” (ibn nukta) (Shehata 75).Humor is no new addition to Egyptian society. As a matter of fact, William Fry, an American sociologist, notes that the use of humor was present in Egyptian society as early as dynastic times. Indeed, ancient Egyptians were quite advanced in the use of literary devices such as satire. Patrick Houlihan explains that “the ancient Egyptians undoubtedly chuckled at writing that employed wit, satire, word-plays, irony, puns, and other sophisticated literary devices (Houlihan). ” In addition to literature, Houlihan also examines the use of visual humor in tomb-chapel decorations as well as in illustrations on papyri and figured ostraca.Here, it is important to note that the use of social satire in ancient Egyptian society was also linked to criticism of oppressive political figures. For example, a joke that dates back over 4,000 years mocks the pharaoh’s refusal to partake in the common man’s activities. Essentially, by stating that the only way to convince the pharaoh to fish is by placing naked girls in the fishing nets, this form of social humor represents a larger political message. The use of humor in Egyptian society continued to evolve as history wore on. After the age of dynasties and during Roman rule, Egyptian advocates were legally banned from practicing law because of a known tendency to employ wit and humor in their work. Romans found such behavior offensive to the serious nature of the profession.This historic and foundational use of humor has certainly had a major influence on the way humor manifests in Egypt’s contemporary society. Certain scholars such as Samer Shaheta argue that Egyptian social humor took on a new form after a group of military leaders called the Free Officers the corrupt monarchy of King Farouk and replaced it with a military regime (Shaheta 83). With the new regime came many modifications and Egyptians gained the right to organize political parties, as well as the rights to free speech and press. But, the military rulers who governed Egypt for the second half of the twentieth century (Nasser, Sadat, and Mubarak) still paid limited amounts of attention to human rights or the principle of democracy.Social humor, however, is unique in that it is able to thrive in an authoritarian society because it is in many cases difficult to censor. The government’s difficulty in censoring social satire and political jokes comes partially from an oral culture. Because such jokes are often told during informal setting through word of mouth, the government is unable to conduct thorough censorship. In Egypt, this kind of social humor has been referred to as “nukta”, which can be explained as a verbal cartoon. The “nukta” is a verbal exchange between people that serves as an oral editorial with critical value. All the same, any Egyptian “nukta” makes its statement through humorous means.Contemporary Egyptian society therefore finds itself in a situation where an age old tradition of joke telling, social injustice, and a limited amount of free speech all coexist. Accordingly, Egyptian political leaders and their regimes became the primary targets of political criticism in the form of jokes. With a deeply entrenched historical and contemporary tradition of incorporating humor into society, the Egyptian tendency to use these elements is only logical when it comes to the revolution of 2011. During the revolution, the Egyptian protesters and activists were able to take joke telling and humor, something with which they were already strongly familiar, to another level. In a way, the age old tradition of political and social humor took on an evolved form, reaching a new height during the Arab Spring.The Political Cartoon as an Accessory to Revolution:Today, it is difficult to imagine political humor without the existence of the political cartoon. Throughout the world, political cartoons are a humoristic approach to political and social commentary. At times they are laughter-invoking and at times, they depict the darkest aspects of political structures. But regardless of the message they convey, political cartoons are a unique part of political humor in the contemporary age and they certainly played an important role during the Arab Spring.The earliest pictorial cartoons can be traced to ancient Egypt. The bas-relief dating from 2000 BC is now kept at a museum in Cairo. Whereas pictorial cartoons may have first been seen in historic Egypt, the usage of political cartoons in Egypt is a much more recent development. Furthermore, circulating and publishing political cartoons has historically been a difficult task due to censorship and autocratic governing systems.In the last sixty years, however, political cartoons were placed into a grey area between being entirely censored and entirely permitted. This semi-censored type of cartoon became of utmost importance during the Arab Spring of 2011. Under Mubarak, although cartoonists did have the right to publish critical political cartoons, their freedoms were greatly limited by the government. These limitations forced political cartoonists to display their messages subliminally through indirect messages. Even during the uprisings, political cartoonists had to go through profound obstacles in order to send their humorous messages to the Egyptian people. Even during the protests and the buildup toward revolution, if a cartoonist wished to publish a political cartoon, he or she would not be allowed to draw a specific political figure. One contemporary political cartoonist from Egypt named Sherif Arafa explains his strategy to continue making political jokes in the face of government oppression. During Mubarak’s regime, the artist created a figure called “the Responsible” who represents the top political figures. Arafa says, “I draw him differently every time so he can have the physical characteristics and age of the top officials I want to criticize. My readers understand whom I mean by the context of the cartoon (Tomoe).” Until Mubarak stepped down in February, directly attacking the government through this form of social humor was extremely dangerous in Egypt. Cartoonists were often arrested, kidnapped, and tortured if they attempted to publish overtly critical political jokes. Even considering these risks, cartoonists such as Arafa strategically used this form of humor to relay their political messages as the revolution began to take form.Additionally, cartoonists were able to start publishing more overtly critical jokes after the president stepped down and his regime toppled. Below are two political cartoons published in Egyptian news sources. The cartoon on the left was published in January before the leader resigned while the cartoon on the right was published after Mubarak’s resignation and depicts a caricature that bears a much stronger resemblance to the former president. The second cartoon is clearly showing an Egypt full of light as the shadow of Mubarak is removed. Whereas the first cartoon is humorous and equally amusing, the second cartoon indicates that the revolution had a great impact in Egypt.

Humor and Hardship Explained:Without understanding the link between humor and hardship, which is an important sociological phenomenon, it is impossible to grasp why this logic can accordingly be applied to the Egyptian case. In his latest piece published in Foreign Policy, Issander El Armani explains this phenomenon through the everyday Egyptians’ perspective. He underlines that “in Egypt's highly dense, hyper-social cities and villages, jokes are nearly universal icebreakers and conversation-starters, and the basic meta-joke, transcending rulers, ideology, and class barriers, almost always remains the same: Our leaders are idiots, our country's a mess, but at least we're in on the joke together (El Amrani).” This means that in Egyptian society, people are able to find a sense of solidarity in times of hardship through the use of humor. Because the lack of democratic power was precisely the issue at hand during the 2011 revolution, the historically entrenched combination of humor, humiliation, and hardship became a potent social tool for Egyptians activists.The relationship between humor and humiliation is one that is both logical as well as sociologically salient. As Iman Mersal of the University of Alberta in Canada points out in a narrative discussing the case of modern day Egypt, mocking political elites and ridiculing them through any possible means serves as a form of resistance. She writes that Egyptians “have resisted humiliation by humiliating the sources of oppression; perhaps humor helped us survive the nightmare (Mersal 669).” This means that by exposing their leadership’s inadequacies and incompetence through humor, the Egyptian people make light of their own situation. This idea’s roots can be found in a Freudian analysis of humor where he claims that “by making our enemy small, inferior, despicable or comic, we achieve in a roundabout way the enjoyment of overcoming him (Freud 103).” In this way, jokes and humor are themselves a cathartic form of rebellion and indirect liberation. That is to say that in contemporary society, by attempting to rebel through humor, Egyptians have succeeded in diverting attention away from the humiliation of being politically powerless.Before Mubarak was overthrown, the Egyptian people had been ruled by a single leader for over three decades. In addition, they had been living under Emergency Law since 1967. Considering both of these points, it is safe to argue that they have been victims of a thoroughly repressive social and political national structure. However, it is also important to note that Egyptians, unlike the citizens of neighboring nations, have had relatively extensive freedom of expression when it comes to social satire. As mentioned previously, due to the revolution in 1952, Egyptians do legally hold the right to freedom of speech and freedom of press. With that said, the authoritarian structure in place in Egypt combined with the aforementioned freedom of expression creates the ideal circumstances in which humor can serve as a political tool to motivate as well as inspire.Here, it is crucial to understand that for Egyptians, the use of humor has served as an outlet- an escape- from the indisputable gravity of reality. This statement holds true throughout modern Egyptian history and is especially true for the uprisings in 2011. In strictly technical terms, the protests in Tahrir square were extremely exhausting on physical, psychological, and emotional levels. Personal accounts from protesters document physical presence in the square for weeks on end. At the peak of the uprising, thousands of Egyptian protesters did not have the opportunity to go home to eat or even shower for several days on end.The aforementioned conditions under which protesters constructed the uprisings are precisely what render the use of humor so pertinent to the recent Egyptian revolution. In order for the protesters to have the capacity to brave all aspects of protesting for weeks on end, social humor served as an undoubtedly needed source of energy and inspiration. The Atlantic, a mainstream American media source, published that “the steady stream of comedy flowing throughout the square functioned to build community, strengthen solidarity, and provide a safe, thug-free outlet for Egyptians to defy the regime (Sousmann).” By building a safe sense of community, political jokes and social satire were critical to diverting attention away from the sheer difficulty of actualizing a revolution and added positivity to an otherwise exhausting and difficult process.How the Internet Transmits Humor Worldwide:When it comes to the Arab Spring, the pertinence of the internet has perhaps been the single most discussed element of the uprisings. Throughout the world, scholars are publishing works on the impact of the internet, specifically social media, in the Arab revolutions. Many have gone so far as to refer to the movements as the “Facebook Revolutions”. In fact, the internet has been a massive public forum through which suggestions, ideas, and thoughts are shared. Whether the internet was used to organize events or to transmit data, it served a critical role in helping the Arab revolutions come to life. In the case of social humor in Egypt, the internet transmitted and instantly spread Egyptians’ jokes and satire throughout the world. It helped transmit revolution-related jokes created in Egypt to populations outside the country. On a sociological level, the internet exposed the soul of the Egyptian revolution, which was a movement based on nonviolence and positivity. Adel Iskander, a medial scholar and lecturer at Georgetown University, comments on the importance of the internet in spreading humor. Iskander observes that "Photographs from Tahrir of people carrying hilarious signs went viral within minutes of posting," In this way, sharing a laugh, often in real time, created "a sense of solidarity and camaraderie among those who supported the cause (Sousmann)." By serving as a forum to publically display the social humor used during the revolution to billions of people, the internet helped show the global community that the Egyptian activists in Cairo intended to achieve their ends through peaceful means and with positive spirits. Although this may seem to be a rather elementary element of a revolutionary movement, the image of the Egyptian uprising as a phenomenon rooted in positivity was an extremely important part of gaining popular support from the outside world. A key part of this image was the social humor used during the revolution and it is largely thanks to the internet that the revolutionary humor was spread worldwide.Humor blogs are one example of the internet and social satire coming together during the Egyptian revolution. Online blogs first appeared in the late 1990’s as a virtual form of the classical journal (O’Sullivan 54). Blogs have since been an electronic record through which individuals from all walks of life share information on the World Wide Web. Over a decade after they first appeared, blogs have revolutionized journalism and serve as an important source of information to online users throughout the world. In the case of the Egyptian uprising in 2011, humor blogs have been extremely efficient in consolidating different examples of social humor in one place. This means that by accessing an online humor blog from any location in the world, an individual has access to a compilation of social humor used during the Egyptian revolution.Humor blogs, whether they are written by professional journalists or amateur enthusiasts, have the potential to reach millions of people. One example of a humor blog that documents social satire in Egypt is called “Egypt Jokes”. This Arabic language blog (also translatable to English) is subscribed to by over 5000 people and hosts a similar following on Faceboook. On the blog, one can find nearly daily postings of political humor and social satire coming from the country of Egypt. In the blog’s archives, one can access numerous entries that focus specifically on the Egyptian revolution. “The Arabist” is another example of a site that serves a similar purpose. Although the website is dedicated to Middle Eastern culture and politics, it hosts a blog with numerous entries dedicated specifically to Egyptian humor throughout the revolution. “The Arabist” blog brings together entire lists of jokes used by Egyptian protesters throughout the revolution. By enabling people to browse collections of jokes that are dated to the time of the uprisings, such blogs are quintessential to spreading the social humor that was such a pertinent part of the Egyptian revolution.Social media networks such as Twitter and Facebook have been an absolutely instrumental part of the Egyptian revolution. The importance of social media websites also holds true when it comes to incorporating humor into the uprisings. As Facebook and Twitter became increasingly instrumental to organizing events and calling for action, they also became fast and simple ways to spread Egyptian jokes throughout the world. For example, Facebook fan pages that mocked president Hosni Mubarak began to appear and collect a fan base (El Amrani). Twitter also became a key public forum for spreading jokes concerning the revolution. On February 11th, 2011, then president Mubarak resigned from his position. Mubarak arrived late to make his resignation speech and even in such a severe moment of international tension, jokes about the topic began to circulate on Twitter. Twitter was filled with theories explaining his late arrival and thousands began to use the hash-tag “ReasonsWhyMubarakIsLate”. Below are several examples of such jokes from users across the world.@TWlTTERWHALE: He's trying to Google Map Saudi Arabia but forgot he shut down the internet. #ReasonsMubarakIsLate@inaweoftahrir: Every time he is ready to leave, there's a damn curfew in place. #ReasonsMubarakIsLate@DHV74: His Pyramid hasn't been completed yet?! #ReasonsMubarakIsLateIn addition to humor blogs and social media networks, the internet has been instrumental in making political cartoons available to billions over the web. For example, the well known political cartoonist Sherif Arafa’s works appear in publications all over the world. He has illustrated a plethora of works concentrating on Mubarak, his regime, and the Egyptian revolution in general. Thanks to the internet and special interest websites, individuals and activists can access entire collections of Arafa’s works in one place. Arafa, as well as other notable Egyptian cartoonists, have profiles on The Cartoon Movement, which is a website dedicated to providing high quality political cartoons to masses of people.Essentially, the internet is the single most powerful tool for consolidating and spreading data. By serving as a database for entire collections of jokes, cartoons, and other forms of satire, the internet has been a key counterpart of transmitting the ideals of the Egyptian revolution to populations that may otherwise have not had access to such information.Mubarak as the main character:In the case of Egypt, Hosni Mubarak was more than just an authoritative ruler; he essentially represented the primary reasons behind the Egyptian people’s discontent. As a result, Mubarak was also the primary target of criticism and critique, and during the Arab Spring, Mubarak became a unique and special part of Egypt’s social humor. Egyptian mockery of Mubarak did not begin in 2011, but during the revolution, Mubarak’s persona was a constant source of inspiration for Egyptian satire and jokes. In many ways, the despised ruler simultaneously served as a much needed focus for Egyptian social humor. One could even argue that Mubarak was the fundamental character without whom Egyptian revolutionary humor could not have evolved during the past year.Hisham Kassem, one of Egypt’s most prominent publishers and democracy activists claims that the Mubarak regime has harbored more political jokes than any of the preceding rulers. He notes that "Under Sadat, it was the poor people left behind by economic liberalization who told the jokes. But under Mubarak, everyone is telling jokes (El Amrani)." In many ways, Mubarak became the poster child of Egyptian humor throughout the revolution because he was both an easy and deserving target. He represented the repression against which the Egyptian people were fighting, and as such became the central focus of their mockery. Jokes about the ruler’s persistence included punch lines such as ‘The carpenters’ union likes to ask Mr. Mubarak: What kind of glue do you use?’ or ‘Use Hosni Glue. Sticks for 30 years’. During the revolution, although Mubarak was a difficult man to oust, he was an incredibly vulnerable target for political and social mockery. Because they were so numerous and therefore socially powerful, Egyptian protestors could openly and directly attack the ruler through humor without the fear of being punished or censored. For the first time in thirty years, the Egyptian people held social superiority, even if they still lacked political strength and democratic rights.Foreign Policy, a division of Washington Post and Newsweek, even published a slideshow in the beginning of 2011 explaining why Mubarak is such a desirable topic for Egyptian social humor. The slideshow translates common Egyptian jokes that came from the demonstrations in Cario and pairs the jokes with a visual display.The Dialogue between Egyptian Jokes and Western Humor:For a number of reasons, many of which I have discussed earlier in this paper, Egyptian revolutionary humor did not stay confined within the borders of North Africa. Today in 2012, the Egyptian jokes shared in Tahrir Square as the Mubarak regime toppled have made their way to all corners of the world. In fact, Egyptian social humor has successfully inspired an entire wave of jokes in the Western world; Egyptian humor has been the foundational building block upon which humorists in Europe and the United States have been able to construct their own jokes concerning the topic of the Arab Spring. In this way, humor from the Arab World has inspired and breathed life into humor in the West.An example of Egyptian humor culture spreading to the West is the colloquial use of the word “Mubarak” as a verb in English speaking countries. Of course, no English dictionary provides the word “Mubarak” as a grammatically correct verb, but that is not the point in this case. Here, it is important to point out that the Egyptian focus on the president’s persona and the Egyptian use of Mubarak as the primary target of social humor in the 2011 revolutions has inspired this Western joke. In the past year, there have been endless jokes in Egypt’s about Mubarak’s sheer refusal to step down from his post. Based on this idea, a joke was born in the West where “mubaraking” referred to a refusal to see reality or to overstay one’s welcome. Urban Dictionary, an English language site dedicated to providing informal definitions for colloquial terms, states that “mubaraking” means “to stay around especially when unwanted.”In this way, where the joke about Mubarak overstaying his welcome is a strictly Egyptian humoristic concept, its social implications have in fact spread across the world. These Egyptian jokes have been a source of inspiration for numerous Western comedians. The associate editor of United States based US News, Joshua Norman, has published an online piece with a collection of well-known American humorists’ referrals to Egyptian social humor. He cites names such as Bill Maher and Conan O’Brian as individuals who have drawn inspiration from Egyptian social humor for their own material. Bill Maher has even made a joke that refers to Mubarak’s fat cats, an originally Arabic term for the former ruler’s closest associates: “All of the Arab potentates and their fat cat entourages are on the run. Tunisia's president is leaving, Mubarak is not going to run for re-election, the guy in Yemen is going to leave. This is great news -- not necessarily for the Middle East, but for real estate agents in Beverly Hills (Norman).” Western jokes of this nature are important examples of how Egyptian social humor has spread to, and inspired, the West.Accordingly, Egyptian-inspired humor has also made its way into Western political cartoons. Throughout the evolution of the Arab Spring, the vast majority of cartoonists in Europe and the United States relied on Egyptian sources as the basis of their jokes. Indeed, there have been distinct parallels between themes and ideas used in Egyptian and Western political cartoons. In this case, there is a type of social domino effect involved. Firstly, Egyptian political cartoonists draw inspiration from Egyptian social humor, and then political cartoonists throughout the world take inspiration from Egyptian cartoonists. Thus there is a constant connection between Egyptian political humor and the rest of the world.In addition, it is important to note that there has been a continuous dialogue between Egyptian and Western humor due to tools such as the internet. Whereas social humor in Egypt may otherwise not be accessible to populations outside its borders and vice versa, the internet allows for the creation of a flow between two worlds of humor. Again, social networking sites are pertinent to this process. For example, a well known American comedian Andy Borowitz, updated his Twitter feed multiple times a day with jokes about the Egyptian regime during the height of the revolution. He has nearly 164,000 followers on Twitter. Borowitz tweets satirical statements such as: "BREAKING: Mubarak has agreed to depart, but insists on taking JetBlue, so departure will be delayed." Again, this type of joke is an extension of a traditionally Egyptian interpretation of the former ruler’s tendency to stay put for much longer than he is desired. Specifically, an online transmission of Egyptian-inspired jokes speaks for the fluidity of social humor in the modern day and age. It essentially illustrates the globalization of social phenomena. In certain ways, it shows that social humor is no longer distinct to one country or to one population. Instead, social humor is becoming more universal because it draws inspiration from jokes and satire found in other places. The case of the social humor in the Egyptian revolution helps to showcase this.The globalization of humor during the Arab Spring is also illustrated by the widespread use of foreign language during the demonstrations and protests. Thousands of Egyptian protesters used multiple languages to transmit their satirical messages throughout the world. Most notable was the widespread use of English in the revolutionary humor. The protesters in Cairo held up signs in the English language even though Egypt is an overwhelmingly Arabic-speaking country. The majority of these jokes were inspired by Egyptian tradition or completely translated, and thus they bore certain linguistic imperfections. Their messages and punch lines, however, had universal appeal. By protesting in Arabic, English, and other languages, Egyptians indirectly multiplied their political and social reach by millions. Thus, the Egyptian message was accessible to an exponentially larger number of people throughout the world. During the revolution and in its aftermath, English language media was extremely quick to spot out English language jokes used by Egyptian protesters and stream them on major news networks, newspapers, and websites. In addition, social and political jokes are universally appealing due to their lighthearted and fun nature. Therefore, jokes are an effective gateway through which Egyptians could attract attention to their revolutionary principles.Humor’s Place in Egypt’s Future:Today, Egypt finds itself at a crossroads. It is trapped between a past dominated by Mubarak’s regime and an unclear future. With military rule still in place and their former ruler’s fate undecided, the Egyptian people’s revolution is not altogether complete. Whereas the Arab Spring brought down the Mubarak regime, democracy in Egypt has yet to be achieved. Recent events such as human rights violations against Christian minorities beg the question as to whether or not Egypt’s future will truly involve democracy. Skeptical minds suspect that Mubarak’s regime will merely be replaced by an equally unjust system of governance. Optimists hold onto hope that the revolutionary process is still in full swing and that fair elections will represent the true voice of the Egyptian people.When it comes to the role of humor in the Egypt of the future, it is difficult to predict how instrumental political and social satire will continue to be. It appears as though the spirit of the revolution has changed. Nearly one year after hopeful and lively protestors filled the streets and flooded Cairo, the Egyptian people find themselves in possession of a new set of problems. Egyptians today are still uncertain whether or not their efforts were in vain. Anxious to see the tangible effects of their efforts, Egyptians are moving toward a more grave and demanding approach to protestation.With that said, it stands to reason that perhaps the use of humor will also decrease in the second wave of the Egyptian revolution. After all, there is an entirely new set of unanswered questions. The revolution no longer revolves around the removal of a ridiculous and universally hated leader. Mubarak jokes no longer have a true place in the Egyptian movement. Facebook and Twitter jokes have too seen their fame. Today, Egyptians are invested in seeing democracy flourish. They are in many ways, tired of waiting for the effects of their revolution to kick in. Regardless of what the future will bring for humor in the second wave of the Egyptian revolution, it is impossible to deny it criticality in the first mobilization last year. Without the social use of humor, the Arab Spring would have been an entirely different movement defined by a totally different set of principles. Without political and social satire, these movements would have manifested in an entirely different and less inspirational fashion.Works Cited:El Amrani, Issander. "Three Decades of a Joke that Just Won't Die." Foreign Policy. 012 2011:n. page. Print. http://www.foreignpolicy.com/articles/2011/01/02/three_decades_of_a_joke_that_just_wont_die?hidecomments=yesFreud, Sigmund, Jokes and Their Relation to the Unconscious (New York, 1960), p. 103.Houlihan, Patrick. Wit and Humour in Ancient Egypt. The Rubicon Press, 2001.Mersal, Iman (2011): Revolutionary Humor, Globalizations, 8:5, 669-674Norman , Joshua. "Have Your In-Laws Mubaraked? ... and Other Egypt Humor." CBS News 08 002 2011, n. pag. Print. http://www.cbsnews.com/8301-503543_162-20030979-503543.htmlO’Sullivan, Catherine. Diaries, On-Line Diaries, and the Future Loss to Archives; Or, Blogs and the Blogging Bloggers Who Blog Them.. The American Archivist , Vol. 68, No. 1 (Spring - Summer, 2005), pp. 53-73Rohm, Frederic. "American and Arab Cultural Lenses." Inner Resources for Leaders REgent University. n. page 3. Print.Shehata, Samer S. 1992. The Politics of Laughter: Nasser, Sadat, and Mubarek in Egyptian Political Jokes. Folklore 103:75-91.Soussman, Anna. "Laugh, O Revolution: Humor in the Egyptian Uprising." Atlantic. 23 002 2011: n. page. Print. http://www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2011/02/laugh-o-revolution-humor-in-the-egyptian-uprising/71530/Tornoe, Rob. "How Political Cartoons Ousted Egyptian President Hosni Mubarak." Politically Illustrated. N.p., n.d. Web. 7 Jan 2012. http://politicallyillustrated.com/index.php/news_page/iw/2444/Images By Sherif Arafa at Cartoon Movement

Humor and Hardship Explained:Without understanding the link between humor and hardship, which is an important sociological phenomenon, it is impossible to grasp why this logic can accordingly be applied to the Egyptian case. In his latest piece published in Foreign Policy, Issander El Armani explains this phenomenon through the everyday Egyptians’ perspective. He underlines that “in Egypt's highly dense, hyper-social cities and villages, jokes are nearly universal icebreakers and conversation-starters, and the basic meta-joke, transcending rulers, ideology, and class barriers, almost always remains the same: Our leaders are idiots, our country's a mess, but at least we're in on the joke together (El Amrani).” This means that in Egyptian society, people are able to find a sense of solidarity in times of hardship through the use of humor. Because the lack of democratic power was precisely the issue at hand during the 2011 revolution, the historically entrenched combination of humor, humiliation, and hardship became a potent social tool for Egyptians activists.The relationship between humor and humiliation is one that is both logical as well as sociologically salient. As Iman Mersal of the University of Alberta in Canada points out in a narrative discussing the case of modern day Egypt, mocking political elites and ridiculing them through any possible means serves as a form of resistance. She writes that Egyptians “have resisted humiliation by humiliating the sources of oppression; perhaps humor helped us survive the nightmare (Mersal 669).” This means that by exposing their leadership’s inadequacies and incompetence through humor, the Egyptian people make light of their own situation. This idea’s roots can be found in a Freudian analysis of humor where he claims that “by making our enemy small, inferior, despicable or comic, we achieve in a roundabout way the enjoyment of overcoming him (Freud 103).” In this way, jokes and humor are themselves a cathartic form of rebellion and indirect liberation. That is to say that in contemporary society, by attempting to rebel through humor, Egyptians have succeeded in diverting attention away from the humiliation of being politically powerless.Before Mubarak was overthrown, the Egyptian people had been ruled by a single leader for over three decades. In addition, they had been living under Emergency Law since 1967. Considering both of these points, it is safe to argue that they have been victims of a thoroughly repressive social and political national structure. However, it is also important to note that Egyptians, unlike the citizens of neighboring nations, have had relatively extensive freedom of expression when it comes to social satire. As mentioned previously, due to the revolution in 1952, Egyptians do legally hold the right to freedom of speech and freedom of press. With that said, the authoritarian structure in place in Egypt combined with the aforementioned freedom of expression creates the ideal circumstances in which humor can serve as a political tool to motivate as well as inspire.Here, it is crucial to understand that for Egyptians, the use of humor has served as an outlet- an escape- from the indisputable gravity of reality. This statement holds true throughout modern Egyptian history and is especially true for the uprisings in 2011. In strictly technical terms, the protests in Tahrir square were extremely exhausting on physical, psychological, and emotional levels. Personal accounts from protesters document physical presence in the square for weeks on end. At the peak of the uprising, thousands of Egyptian protesters did not have the opportunity to go home to eat or even shower for several days on end.The aforementioned conditions under which protesters constructed the uprisings are precisely what render the use of humor so pertinent to the recent Egyptian revolution. In order for the protesters to have the capacity to brave all aspects of protesting for weeks on end, social humor served as an undoubtedly needed source of energy and inspiration. The Atlantic, a mainstream American media source, published that “the steady stream of comedy flowing throughout the square functioned to build community, strengthen solidarity, and provide a safe, thug-free outlet for Egyptians to defy the regime (Sousmann).” By building a safe sense of community, political jokes and social satire were critical to diverting attention away from the sheer difficulty of actualizing a revolution and added positivity to an otherwise exhausting and difficult process.How the Internet Transmits Humor Worldwide:When it comes to the Arab Spring, the pertinence of the internet has perhaps been the single most discussed element of the uprisings. Throughout the world, scholars are publishing works on the impact of the internet, specifically social media, in the Arab revolutions. Many have gone so far as to refer to the movements as the “Facebook Revolutions”. In fact, the internet has been a massive public forum through which suggestions, ideas, and thoughts are shared. Whether the internet was used to organize events or to transmit data, it served a critical role in helping the Arab revolutions come to life. In the case of social humor in Egypt, the internet transmitted and instantly spread Egyptians’ jokes and satire throughout the world. It helped transmit revolution-related jokes created in Egypt to populations outside the country. On a sociological level, the internet exposed the soul of the Egyptian revolution, which was a movement based on nonviolence and positivity. Adel Iskander, a medial scholar and lecturer at Georgetown University, comments on the importance of the internet in spreading humor. Iskander observes that "Photographs from Tahrir of people carrying hilarious signs went viral within minutes of posting," In this way, sharing a laugh, often in real time, created "a sense of solidarity and camaraderie among those who supported the cause (Sousmann)." By serving as a forum to publically display the social humor used during the revolution to billions of people, the internet helped show the global community that the Egyptian activists in Cairo intended to achieve their ends through peaceful means and with positive spirits. Although this may seem to be a rather elementary element of a revolutionary movement, the image of the Egyptian uprising as a phenomenon rooted in positivity was an extremely important part of gaining popular support from the outside world. A key part of this image was the social humor used during the revolution and it is largely thanks to the internet that the revolutionary humor was spread worldwide.Humor blogs are one example of the internet and social satire coming together during the Egyptian revolution. Online blogs first appeared in the late 1990’s as a virtual form of the classical journal (O’Sullivan 54). Blogs have since been an electronic record through which individuals from all walks of life share information on the World Wide Web. Over a decade after they first appeared, blogs have revolutionized journalism and serve as an important source of information to online users throughout the world. In the case of the Egyptian uprising in 2011, humor blogs have been extremely efficient in consolidating different examples of social humor in one place. This means that by accessing an online humor blog from any location in the world, an individual has access to a compilation of social humor used during the Egyptian revolution.Humor blogs, whether they are written by professional journalists or amateur enthusiasts, have the potential to reach millions of people. One example of a humor blog that documents social satire in Egypt is called “Egypt Jokes”. This Arabic language blog (also translatable to English) is subscribed to by over 5000 people and hosts a similar following on Faceboook. On the blog, one can find nearly daily postings of political humor and social satire coming from the country of Egypt. In the blog’s archives, one can access numerous entries that focus specifically on the Egyptian revolution. “The Arabist” is another example of a site that serves a similar purpose. Although the website is dedicated to Middle Eastern culture and politics, it hosts a blog with numerous entries dedicated specifically to Egyptian humor throughout the revolution. “The Arabist” blog brings together entire lists of jokes used by Egyptian protesters throughout the revolution. By enabling people to browse collections of jokes that are dated to the time of the uprisings, such blogs are quintessential to spreading the social humor that was such a pertinent part of the Egyptian revolution.Social media networks such as Twitter and Facebook have been an absolutely instrumental part of the Egyptian revolution. The importance of social media websites also holds true when it comes to incorporating humor into the uprisings. As Facebook and Twitter became increasingly instrumental to organizing events and calling for action, they also became fast and simple ways to spread Egyptian jokes throughout the world. For example, Facebook fan pages that mocked president Hosni Mubarak began to appear and collect a fan base (El Amrani). Twitter also became a key public forum for spreading jokes concerning the revolution. On February 11th, 2011, then president Mubarak resigned from his position. Mubarak arrived late to make his resignation speech and even in such a severe moment of international tension, jokes about the topic began to circulate on Twitter. Twitter was filled with theories explaining his late arrival and thousands began to use the hash-tag “ReasonsWhyMubarakIsLate”. Below are several examples of such jokes from users across the world.@TWlTTERWHALE: He's trying to Google Map Saudi Arabia but forgot he shut down the internet. #ReasonsMubarakIsLate@inaweoftahrir: Every time he is ready to leave, there's a damn curfew in place. #ReasonsMubarakIsLate@DHV74: His Pyramid hasn't been completed yet?! #ReasonsMubarakIsLateIn addition to humor blogs and social media networks, the internet has been instrumental in making political cartoons available to billions over the web. For example, the well known political cartoonist Sherif Arafa’s works appear in publications all over the world. He has illustrated a plethora of works concentrating on Mubarak, his regime, and the Egyptian revolution in general. Thanks to the internet and special interest websites, individuals and activists can access entire collections of Arafa’s works in one place. Arafa, as well as other notable Egyptian cartoonists, have profiles on The Cartoon Movement, which is a website dedicated to providing high quality political cartoons to masses of people.Essentially, the internet is the single most powerful tool for consolidating and spreading data. By serving as a database for entire collections of jokes, cartoons, and other forms of satire, the internet has been a key counterpart of transmitting the ideals of the Egyptian revolution to populations that may otherwise have not had access to such information.Mubarak as the main character:In the case of Egypt, Hosni Mubarak was more than just an authoritative ruler; he essentially represented the primary reasons behind the Egyptian people’s discontent. As a result, Mubarak was also the primary target of criticism and critique, and during the Arab Spring, Mubarak became a unique and special part of Egypt’s social humor. Egyptian mockery of Mubarak did not begin in 2011, but during the revolution, Mubarak’s persona was a constant source of inspiration for Egyptian satire and jokes. In many ways, the despised ruler simultaneously served as a much needed focus for Egyptian social humor. One could even argue that Mubarak was the fundamental character without whom Egyptian revolutionary humor could not have evolved during the past year.Hisham Kassem, one of Egypt’s most prominent publishers and democracy activists claims that the Mubarak regime has harbored more political jokes than any of the preceding rulers. He notes that "Under Sadat, it was the poor people left behind by economic liberalization who told the jokes. But under Mubarak, everyone is telling jokes (El Amrani)." In many ways, Mubarak became the poster child of Egyptian humor throughout the revolution because he was both an easy and deserving target. He represented the repression against which the Egyptian people were fighting, and as such became the central focus of their mockery. Jokes about the ruler’s persistence included punch lines such as ‘The carpenters’ union likes to ask Mr. Mubarak: What kind of glue do you use?’ or ‘Use Hosni Glue. Sticks for 30 years’. During the revolution, although Mubarak was a difficult man to oust, he was an incredibly vulnerable target for political and social mockery. Because they were so numerous and therefore socially powerful, Egyptian protestors could openly and directly attack the ruler through humor without the fear of being punished or censored. For the first time in thirty years, the Egyptian people held social superiority, even if they still lacked political strength and democratic rights.Foreign Policy, a division of Washington Post and Newsweek, even published a slideshow in the beginning of 2011 explaining why Mubarak is such a desirable topic for Egyptian social humor. The slideshow translates common Egyptian jokes that came from the demonstrations in Cario and pairs the jokes with a visual display.The Dialogue between Egyptian Jokes and Western Humor:For a number of reasons, many of which I have discussed earlier in this paper, Egyptian revolutionary humor did not stay confined within the borders of North Africa. Today in 2012, the Egyptian jokes shared in Tahrir Square as the Mubarak regime toppled have made their way to all corners of the world. In fact, Egyptian social humor has successfully inspired an entire wave of jokes in the Western world; Egyptian humor has been the foundational building block upon which humorists in Europe and the United States have been able to construct their own jokes concerning the topic of the Arab Spring. In this way, humor from the Arab World has inspired and breathed life into humor in the West.An example of Egyptian humor culture spreading to the West is the colloquial use of the word “Mubarak” as a verb in English speaking countries. Of course, no English dictionary provides the word “Mubarak” as a grammatically correct verb, but that is not the point in this case. Here, it is important to point out that the Egyptian focus on the president’s persona and the Egyptian use of Mubarak as the primary target of social humor in the 2011 revolutions has inspired this Western joke. In the past year, there have been endless jokes in Egypt’s about Mubarak’s sheer refusal to step down from his post. Based on this idea, a joke was born in the West where “mubaraking” referred to a refusal to see reality or to overstay one’s welcome. Urban Dictionary, an English language site dedicated to providing informal definitions for colloquial terms, states that “mubaraking” means “to stay around especially when unwanted.”In this way, where the joke about Mubarak overstaying his welcome is a strictly Egyptian humoristic concept, its social implications have in fact spread across the world. These Egyptian jokes have been a source of inspiration for numerous Western comedians. The associate editor of United States based US News, Joshua Norman, has published an online piece with a collection of well-known American humorists’ referrals to Egyptian social humor. He cites names such as Bill Maher and Conan O’Brian as individuals who have drawn inspiration from Egyptian social humor for their own material. Bill Maher has even made a joke that refers to Mubarak’s fat cats, an originally Arabic term for the former ruler’s closest associates: “All of the Arab potentates and their fat cat entourages are on the run. Tunisia's president is leaving, Mubarak is not going to run for re-election, the guy in Yemen is going to leave. This is great news -- not necessarily for the Middle East, but for real estate agents in Beverly Hills (Norman).” Western jokes of this nature are important examples of how Egyptian social humor has spread to, and inspired, the West.Accordingly, Egyptian-inspired humor has also made its way into Western political cartoons. Throughout the evolution of the Arab Spring, the vast majority of cartoonists in Europe and the United States relied on Egyptian sources as the basis of their jokes. Indeed, there have been distinct parallels between themes and ideas used in Egyptian and Western political cartoons. In this case, there is a type of social domino effect involved. Firstly, Egyptian political cartoonists draw inspiration from Egyptian social humor, and then political cartoonists throughout the world take inspiration from Egyptian cartoonists. Thus there is a constant connection between Egyptian political humor and the rest of the world.In addition, it is important to note that there has been a continuous dialogue between Egyptian and Western humor due to tools such as the internet. Whereas social humor in Egypt may otherwise not be accessible to populations outside its borders and vice versa, the internet allows for the creation of a flow between two worlds of humor. Again, social networking sites are pertinent to this process. For example, a well known American comedian Andy Borowitz, updated his Twitter feed multiple times a day with jokes about the Egyptian regime during the height of the revolution. He has nearly 164,000 followers on Twitter. Borowitz tweets satirical statements such as: "BREAKING: Mubarak has agreed to depart, but insists on taking JetBlue, so departure will be delayed." Again, this type of joke is an extension of a traditionally Egyptian interpretation of the former ruler’s tendency to stay put for much longer than he is desired. Specifically, an online transmission of Egyptian-inspired jokes speaks for the fluidity of social humor in the modern day and age. It essentially illustrates the globalization of social phenomena. In certain ways, it shows that social humor is no longer distinct to one country or to one population. Instead, social humor is becoming more universal because it draws inspiration from jokes and satire found in other places. The case of the social humor in the Egyptian revolution helps to showcase this.The globalization of humor during the Arab Spring is also illustrated by the widespread use of foreign language during the demonstrations and protests. Thousands of Egyptian protesters used multiple languages to transmit their satirical messages throughout the world. Most notable was the widespread use of English in the revolutionary humor. The protesters in Cairo held up signs in the English language even though Egypt is an overwhelmingly Arabic-speaking country. The majority of these jokes were inspired by Egyptian tradition or completely translated, and thus they bore certain linguistic imperfections. Their messages and punch lines, however, had universal appeal. By protesting in Arabic, English, and other languages, Egyptians indirectly multiplied their political and social reach by millions. Thus, the Egyptian message was accessible to an exponentially larger number of people throughout the world. During the revolution and in its aftermath, English language media was extremely quick to spot out English language jokes used by Egyptian protesters and stream them on major news networks, newspapers, and websites. In addition, social and political jokes are universally appealing due to their lighthearted and fun nature. Therefore, jokes are an effective gateway through which Egyptians could attract attention to their revolutionary principles.Humor’s Place in Egypt’s Future:Today, Egypt finds itself at a crossroads. It is trapped between a past dominated by Mubarak’s regime and an unclear future. With military rule still in place and their former ruler’s fate undecided, the Egyptian people’s revolution is not altogether complete. Whereas the Arab Spring brought down the Mubarak regime, democracy in Egypt has yet to be achieved. Recent events such as human rights violations against Christian minorities beg the question as to whether or not Egypt’s future will truly involve democracy. Skeptical minds suspect that Mubarak’s regime will merely be replaced by an equally unjust system of governance. Optimists hold onto hope that the revolutionary process is still in full swing and that fair elections will represent the true voice of the Egyptian people.When it comes to the role of humor in the Egypt of the future, it is difficult to predict how instrumental political and social satire will continue to be. It appears as though the spirit of the revolution has changed. Nearly one year after hopeful and lively protestors filled the streets and flooded Cairo, the Egyptian people find themselves in possession of a new set of problems. Egyptians today are still uncertain whether or not their efforts were in vain. Anxious to see the tangible effects of their efforts, Egyptians are moving toward a more grave and demanding approach to protestation.With that said, it stands to reason that perhaps the use of humor will also decrease in the second wave of the Egyptian revolution. After all, there is an entirely new set of unanswered questions. The revolution no longer revolves around the removal of a ridiculous and universally hated leader. Mubarak jokes no longer have a true place in the Egyptian movement. Facebook and Twitter jokes have too seen their fame. Today, Egyptians are invested in seeing democracy flourish. They are in many ways, tired of waiting for the effects of their revolution to kick in. Regardless of what the future will bring for humor in the second wave of the Egyptian revolution, it is impossible to deny it criticality in the first mobilization last year. Without the social use of humor, the Arab Spring would have been an entirely different movement defined by a totally different set of principles. Without political and social satire, these movements would have manifested in an entirely different and less inspirational fashion.Works Cited:El Amrani, Issander. "Three Decades of a Joke that Just Won't Die." Foreign Policy. 012 2011:n. page. Print. http://www.foreignpolicy.com/articles/2011/01/02/three_decades_of_a_joke_that_just_wont_die?hidecomments=yesFreud, Sigmund, Jokes and Their Relation to the Unconscious (New York, 1960), p. 103.Houlihan, Patrick. Wit and Humour in Ancient Egypt. The Rubicon Press, 2001.Mersal, Iman (2011): Revolutionary Humor, Globalizations, 8:5, 669-674Norman , Joshua. "Have Your In-Laws Mubaraked? ... and Other Egypt Humor." CBS News 08 002 2011, n. pag. Print. http://www.cbsnews.com/8301-503543_162-20030979-503543.htmlO’Sullivan, Catherine. Diaries, On-Line Diaries, and the Future Loss to Archives; Or, Blogs and the Blogging Bloggers Who Blog Them.. The American Archivist , Vol. 68, No. 1 (Spring - Summer, 2005), pp. 53-73Rohm, Frederic. "American and Arab Cultural Lenses." Inner Resources for Leaders REgent University. n. page 3. Print.Shehata, Samer S. 1992. The Politics of Laughter: Nasser, Sadat, and Mubarek in Egyptian Political Jokes. Folklore 103:75-91.Soussman, Anna. "Laugh, O Revolution: Humor in the Egyptian Uprising." Atlantic. 23 002 2011: n. page. Print. http://www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2011/02/laugh-o-revolution-humor-in-the-egyptian-uprising/71530/Tornoe, Rob. "How Political Cartoons Ousted Egyptian President Hosni Mubarak." Politically Illustrated. N.p., n.d. Web. 7 Jan 2012. http://politicallyillustrated.com/index.php/news_page/iw/2444/Images By Sherif Arafa at Cartoon Movement