SUSTAINABLE FISHERIES IN THE GULF OF CALIFORNIA

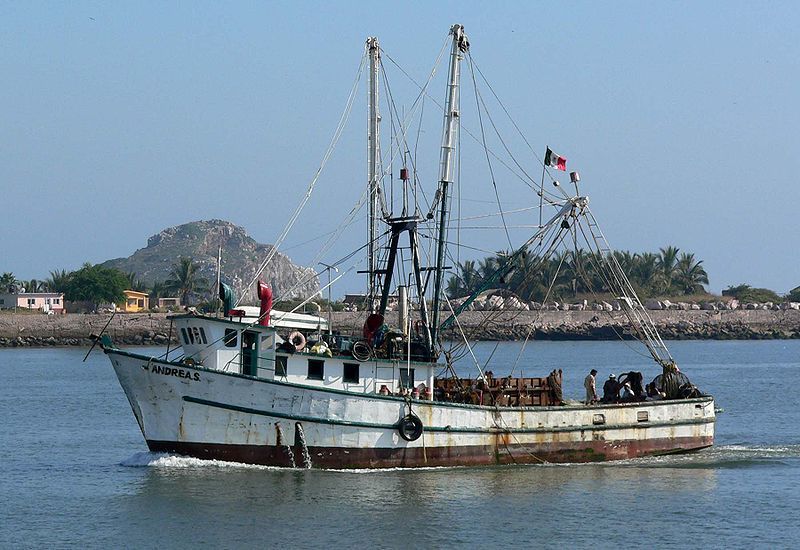

By Melanie EmrStaff WriterLast December, I attended a conference at the Scripps Institute of Oceanography as a member of the Forum on Environmental Change entitled “Sustainable Fisheries in the Gulf of California.” The conference featured a presentation by fisheries researcher Carlos Vasquez that highlighted the devastation caused by overfishing in the Gulf of California. Overfishing occurs when a fish stock depletes faster than it replenishes itself, preventing it from recovering to healthy levels. Destructive overfishing puts vital marine animals at risk. A 2008 report by the United Nations observed that over 80 percent of the world’s most valuable fish stocks are exploited at or beyond their sustainable levels. To put it simply, the ocean’s supply cannot meet growing human demand for seafood. Ever increasing pressure placed on fisheries by overfishing around the world has dangerously depleted them. Unfortunately, this drastic reduction hurts commercial fishermen who rely on catching fish to support their families. Fish populations must be better managed to ensure stable and more sustainable catches into the future. Otherwise, overfishing could cause a global shortage of seafood, robbing billions of their sustenance.Because multiple endangered fish species inhabit its waters, the Gulf of California acts as a key area of research related to the impact of overfishing as well as the implementation of sustainable fisheries. In the context of this article, sustainable fisheries pertain to the “management regime of a sustainable wild-caught species that implements and enforces all local, national and international laws and utilizes a precautionary approach to ensure the long-term productivity of the resource and integrity of the ecosystem.” But while sustainable fishing practices established by the Mexican government and non-governmental organizations in the area protect the biodiversity of the region on paper, state regulations remain unenforced due to conflicts of interest with lucrative commercial fishing industries. The Gulf Corvina, a fish endemic to the northern Gulf of California, is one of the species depleted by fishing malpractices and inefficient management. Already listed as a vulnerable species, it is at risk of being endangered. In an ideal and sustainable situation, wild-caught fish are brought up using techniques that avoid the capture of unwanted or unmarketable species. Such techniques reduce the chances of unintended catch, also known as bycatch, a primary culprit in the drastic reduction of the Corvina population. Bycatch often occurs with the use of oversized nets such as gillnets and trawls. These nets stretch up to as 125 kilometers and bring up to 10,000 tons of fish every year. Despite grassroots organizations’ efforts to implement laws that reduce the size of fishing nets, there are no enforced regulations in place to manage endangered and at-risk fish populations in the Gulf.To make matters worse, the Corvina has a historically low productivity rate, making it especially vulnerable to fishing pressure. However, current regulations dictate that the legal fishing season coincide with the Corvina’s annual spawning event, which results in 90 percent of the Corvina harvested during spawning. In order for establishment of a sustainable Corvina fishery, the steps must be taken to abolish inefficient fishing techniques while taking into account the life-history characteristics of the. However, this is easier said than done since the Corvina fishery generates $4 million in revenue in just over two months.The Totoaba, another fish endemic to the Gulf of California, is listed as a “special protected species” in Mexico that faces global extinction. Illegal fishing and bycatch so severely depleted its population that authorities created a biosphere reserve to promote habitat restoration in 1989. However, the market for Totoaba from the Gulf remains lucrative; the catch exceeds the value of narcotics trafficking, with a single haul selling for around $10,000. High demand for Totoaba liver oil in China plays a key role in determining its value. Fishermen then export the catch to the United States, where it is again exported to the Asian fish markets. This growing demand exceeds the supply of Totoaba, reinforcing the notion that the ocean’s supply cannot meet our growing demand for seafood.In order to protect threatened species such as the Corvina and the Totoaba, spawning grounds must be strictly enforced as “no-take zones.” These no-take zones entail protected areas in which the extraction of any natural or cultural resource is prohibited. However, in order for no-take zones to be effective, activities within their boundaries must be strictly enforced. Since zones designed for fishing provide a less abundant and accessibly supply of fish, fishermen are inclined to take chances and fish in the no-take zones, where yield far more promising catches. Because little enforcement occurs, they often get away with fishing in protected zones, increasing the risk of overfishing.But the real question to consider is the overarching role of the Mexican state, both in matters of enforcement of no-watch zones and matters of controlling fish exports. The park rangers themselves are incapable of any type of enforcement. Little political will exists in Mexico to move in another direction. The National Fisheries Institute in Mexico assesses the status of national fisheries and evaluates fishing gear. Whereas present management measures for coastal fisheries constrain some fishing activity, these measures only denote fishing zones and specify allowable gear. There are no quotas and enforcement of regulations set in place. The Secretariat of Environment and Natural Resources works closely with the Secretary of the Economy, a relationship that places economic growth before environmental protection. Meanwhile, many Mexican political parties argue that the establishment of biosphere reserves in the Gulf of California and other forms of environmental protection impede the country’s economic development, making environmentally friendly reform highly unlikely.As rent-seeking behavior in the Mexican commercial fishing industries demonstrates, environmental administrations under the PRI have shown that they are more committed to economic development than conservation. Many fisheries In Mexico are owned by state-affiliated cooperatives that issue fishing permits and access to fishing grounds. These cooperatives also take a share of the profits. While NGOs and the international community often demonize the fishermen in the Gulf of California for overfishing, the fishermen are in reality at the mercy of the Mexican state’s cooperatives. The administration of fishing permits can be imagined as a feudal system of sorts, a permit regime. The legal framework includes the permit administrator that has capital motivation but no incentive towards resource sustainability. It is the relationship between the permit administrator and the consumer chain that leads to exploitation of the commercial fishermen in the village.The impact of the state-affiliated cooperatives’ hold on fishing permits is nowhere as evident as the Mexican state of Sonora, which spans nearly the entire Gulf. Some 95 percent of villagers in the region work in fisheries. Wages here are extremely volatile. One day, they can be as high as seven pesos for a kilo of fish; the next day it can drop to a single peso. Permit administrators determine the wages. Administrators want more fishermen working to maximize their own profits. Having larger numbers of fishermen drives down wages, forcing fishermen to overfish to make up for the economic disparity.The international community, including NGOs such as the World Wildlife Foundation paints the Mexican fishermen as culprits for using unsustainable techniques that cause overfishing. This is an unjust accusation. The socioeconomic aspect of overfishing must be taken into account—the true criminal is the Mexican state. Unfortunately, Mexican political parties meddle in Mexican industries all too often. Permits are at the heart of this “business power.” Those on the state and federal level control the issuance of fishing permits and participate in extensive lobbying. Meanwhile, local fishing communities are left marginalized from political decision-making and overfish to make ends meet. It is time that the Mexican Senate open up serious discussion on unsustainable fishing techniques promoted by the state-controlled permit holders. Unilateral regulations must cease and investment in government transparency must occur.The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), a scientific agency within the U.S. Department of Commerce has dedicated 20 years to supporting sustainable U.S. fisheries. In that time, it has created a model for other countries to follow that provides btter protection for fisheries. NOAA’s role in the Gulf of Mexico provides a model upon which the Mexican government can draw lessons to improve sustainability in the Gulf of California. It seeks to connect fishermen directly to sustainability politics, creating a relationship that strengthens the nation’s fishery laws. By providing incentives that reward fishermen for applying environmentally friendly practices, ocean ecosystems are preserved. For example, NOAA helped introduce shrimp fishing gear that "reduces environmental impacts, including the number of fish and endangered sea turtles that are caught and incidentally killed." Such innovations are more fuel-efficient and lower costs for fishermen, all the while reducing their carbon admissions. NOAA also actively lobbies the business community to purchase sustainably caught seafood. With the application of such efforts, there has been a successful recovery of species such as the red snapper in the Gulf.To solve the issues associated with fishing in the Gulf, the Mexican government should draw upon the model promoted by the NOAA. Fishermen must be empowered and included in the decision-making process. For this to occur, NGOs must provide funding and international support. Once local fishermen are actively engaged in conversation with the NGOs and are able to voice their personal concerns, NGOs can more efficiently “feed” the needs of the locals and administer a bottom-up grassroots approach rather than a top-down hegemonic approach. Concurrently, NGOs must introduce opportunities that promote sustainability, such as eco-friendly nets while instructing the locals on how to adapt their own socioeconomic situations to the new regulations. Meanwhile, the Mexican state needs to advertise the long-term benefits of the biosphere reserve. Without a commitment to creating and regulating sustainable fisheries, future generations face a world deprived of economically viable and globally nutritious species.Image by eutrophication&hypoxia

By Melanie EmrStaff WriterLast December, I attended a conference at the Scripps Institute of Oceanography as a member of the Forum on Environmental Change entitled “Sustainable Fisheries in the Gulf of California.” The conference featured a presentation by fisheries researcher Carlos Vasquez that highlighted the devastation caused by overfishing in the Gulf of California. Overfishing occurs when a fish stock depletes faster than it replenishes itself, preventing it from recovering to healthy levels. Destructive overfishing puts vital marine animals at risk. A 2008 report by the United Nations observed that over 80 percent of the world’s most valuable fish stocks are exploited at or beyond their sustainable levels. To put it simply, the ocean’s supply cannot meet growing human demand for seafood. Ever increasing pressure placed on fisheries by overfishing around the world has dangerously depleted them. Unfortunately, this drastic reduction hurts commercial fishermen who rely on catching fish to support their families. Fish populations must be better managed to ensure stable and more sustainable catches into the future. Otherwise, overfishing could cause a global shortage of seafood, robbing billions of their sustenance.Because multiple endangered fish species inhabit its waters, the Gulf of California acts as a key area of research related to the impact of overfishing as well as the implementation of sustainable fisheries. In the context of this article, sustainable fisheries pertain to the “management regime of a sustainable wild-caught species that implements and enforces all local, national and international laws and utilizes a precautionary approach to ensure the long-term productivity of the resource and integrity of the ecosystem.” But while sustainable fishing practices established by the Mexican government and non-governmental organizations in the area protect the biodiversity of the region on paper, state regulations remain unenforced due to conflicts of interest with lucrative commercial fishing industries. The Gulf Corvina, a fish endemic to the northern Gulf of California, is one of the species depleted by fishing malpractices and inefficient management. Already listed as a vulnerable species, it is at risk of being endangered. In an ideal and sustainable situation, wild-caught fish are brought up using techniques that avoid the capture of unwanted or unmarketable species. Such techniques reduce the chances of unintended catch, also known as bycatch, a primary culprit in the drastic reduction of the Corvina population. Bycatch often occurs with the use of oversized nets such as gillnets and trawls. These nets stretch up to as 125 kilometers and bring up to 10,000 tons of fish every year. Despite grassroots organizations’ efforts to implement laws that reduce the size of fishing nets, there are no enforced regulations in place to manage endangered and at-risk fish populations in the Gulf.To make matters worse, the Corvina has a historically low productivity rate, making it especially vulnerable to fishing pressure. However, current regulations dictate that the legal fishing season coincide with the Corvina’s annual spawning event, which results in 90 percent of the Corvina harvested during spawning. In order for establishment of a sustainable Corvina fishery, the steps must be taken to abolish inefficient fishing techniques while taking into account the life-history characteristics of the. However, this is easier said than done since the Corvina fishery generates $4 million in revenue in just over two months.The Totoaba, another fish endemic to the Gulf of California, is listed as a “special protected species” in Mexico that faces global extinction. Illegal fishing and bycatch so severely depleted its population that authorities created a biosphere reserve to promote habitat restoration in 1989. However, the market for Totoaba from the Gulf remains lucrative; the catch exceeds the value of narcotics trafficking, with a single haul selling for around $10,000. High demand for Totoaba liver oil in China plays a key role in determining its value. Fishermen then export the catch to the United States, where it is again exported to the Asian fish markets. This growing demand exceeds the supply of Totoaba, reinforcing the notion that the ocean’s supply cannot meet our growing demand for seafood.In order to protect threatened species such as the Corvina and the Totoaba, spawning grounds must be strictly enforced as “no-take zones.” These no-take zones entail protected areas in which the extraction of any natural or cultural resource is prohibited. However, in order for no-take zones to be effective, activities within their boundaries must be strictly enforced. Since zones designed for fishing provide a less abundant and accessibly supply of fish, fishermen are inclined to take chances and fish in the no-take zones, where yield far more promising catches. Because little enforcement occurs, they often get away with fishing in protected zones, increasing the risk of overfishing.But the real question to consider is the overarching role of the Mexican state, both in matters of enforcement of no-watch zones and matters of controlling fish exports. The park rangers themselves are incapable of any type of enforcement. Little political will exists in Mexico to move in another direction. The National Fisheries Institute in Mexico assesses the status of national fisheries and evaluates fishing gear. Whereas present management measures for coastal fisheries constrain some fishing activity, these measures only denote fishing zones and specify allowable gear. There are no quotas and enforcement of regulations set in place. The Secretariat of Environment and Natural Resources works closely with the Secretary of the Economy, a relationship that places economic growth before environmental protection. Meanwhile, many Mexican political parties argue that the establishment of biosphere reserves in the Gulf of California and other forms of environmental protection impede the country’s economic development, making environmentally friendly reform highly unlikely.As rent-seeking behavior in the Mexican commercial fishing industries demonstrates, environmental administrations under the PRI have shown that they are more committed to economic development than conservation. Many fisheries In Mexico are owned by state-affiliated cooperatives that issue fishing permits and access to fishing grounds. These cooperatives also take a share of the profits. While NGOs and the international community often demonize the fishermen in the Gulf of California for overfishing, the fishermen are in reality at the mercy of the Mexican state’s cooperatives. The administration of fishing permits can be imagined as a feudal system of sorts, a permit regime. The legal framework includes the permit administrator that has capital motivation but no incentive towards resource sustainability. It is the relationship between the permit administrator and the consumer chain that leads to exploitation of the commercial fishermen in the village.The impact of the state-affiliated cooperatives’ hold on fishing permits is nowhere as evident as the Mexican state of Sonora, which spans nearly the entire Gulf. Some 95 percent of villagers in the region work in fisheries. Wages here are extremely volatile. One day, they can be as high as seven pesos for a kilo of fish; the next day it can drop to a single peso. Permit administrators determine the wages. Administrators want more fishermen working to maximize their own profits. Having larger numbers of fishermen drives down wages, forcing fishermen to overfish to make up for the economic disparity.The international community, including NGOs such as the World Wildlife Foundation paints the Mexican fishermen as culprits for using unsustainable techniques that cause overfishing. This is an unjust accusation. The socioeconomic aspect of overfishing must be taken into account—the true criminal is the Mexican state. Unfortunately, Mexican political parties meddle in Mexican industries all too often. Permits are at the heart of this “business power.” Those on the state and federal level control the issuance of fishing permits and participate in extensive lobbying. Meanwhile, local fishing communities are left marginalized from political decision-making and overfish to make ends meet. It is time that the Mexican Senate open up serious discussion on unsustainable fishing techniques promoted by the state-controlled permit holders. Unilateral regulations must cease and investment in government transparency must occur.The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), a scientific agency within the U.S. Department of Commerce has dedicated 20 years to supporting sustainable U.S. fisheries. In that time, it has created a model for other countries to follow that provides btter protection for fisheries. NOAA’s role in the Gulf of Mexico provides a model upon which the Mexican government can draw lessons to improve sustainability in the Gulf of California. It seeks to connect fishermen directly to sustainability politics, creating a relationship that strengthens the nation’s fishery laws. By providing incentives that reward fishermen for applying environmentally friendly practices, ocean ecosystems are preserved. For example, NOAA helped introduce shrimp fishing gear that "reduces environmental impacts, including the number of fish and endangered sea turtles that are caught and incidentally killed." Such innovations are more fuel-efficient and lower costs for fishermen, all the while reducing their carbon admissions. NOAA also actively lobbies the business community to purchase sustainably caught seafood. With the application of such efforts, there has been a successful recovery of species such as the red snapper in the Gulf.To solve the issues associated with fishing in the Gulf, the Mexican government should draw upon the model promoted by the NOAA. Fishermen must be empowered and included in the decision-making process. For this to occur, NGOs must provide funding and international support. Once local fishermen are actively engaged in conversation with the NGOs and are able to voice their personal concerns, NGOs can more efficiently “feed” the needs of the locals and administer a bottom-up grassroots approach rather than a top-down hegemonic approach. Concurrently, NGOs must introduce opportunities that promote sustainability, such as eco-friendly nets while instructing the locals on how to adapt their own socioeconomic situations to the new regulations. Meanwhile, the Mexican state needs to advertise the long-term benefits of the biosphere reserve. Without a commitment to creating and regulating sustainable fisheries, future generations face a world deprived of economically viable and globally nutritious species.Image by eutrophication&hypoxia