HI-TECH IN THE ROUGH: THE DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF CONGO'S RESOURCE CURSE

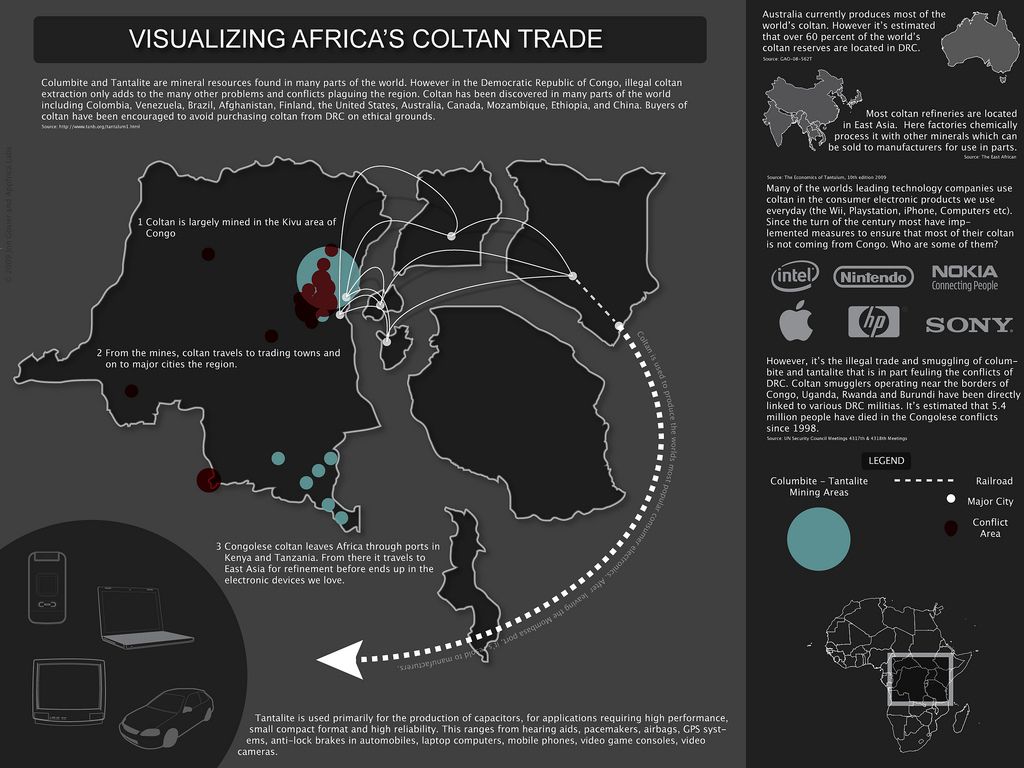

By Andrew KimStaff WriterToday’s smartphones are touted to have some of the fastest microprocessors and brightest displays screens capable of functions previously restricted to huge desktop computers, and yet they come at a cost of just a few hundred dollars at retail price. However, a look into the high-tech industry—and more specifically, the industry that assembles the components behind such gadgets—reveals a myriad of hidden costs that often surmount from exploitation and violence.Tantalum is considered one of the most critical components in modern day high-tech gadgets, used in everything from Nokia phones to Sony stereos and Samsung computers. In fact, the mineral has become so critical that it has been referred to as “magic dust.” Tantalum is a power that is made by refining coltan, which currently sells for $100 per pound. The market for tantalum is huge, as roughly 6.6 million pounds of tantalum are used around the world, with “60 percent finding its way into the electronics industry.” The United States is also the world’s largest consumer of tantalum, accounting for around 40 percent of global demand.What is alarming about tantalum is that is that the vast majority of it stems from Africa, with over 50 percent of tantalum coming from the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC). The rush for coltan and tantalum brought in an estimated $20 million a month to rebel groups and militia operating from northeastern DRC. Peasants perform most of the coltan mining in the DRC, with an estimated 30 percent of schoolchildren in northeastern DRC having abandoned their studies in pursuit of mining coltan.From the perspective of the consumer, it is hard to press tech-related companies to use tantalum that has been processed and mined in an environmentally and ethically friendly manner. Before the coltan reaches large regional traders, multiple intermediaries, sometimes up to six, can be involved. Due to this, firms and companies have difficulty in determining if the intermediaries are rebel forces or militia groups. Outi Mikkonen, Communications Manager for Environmental Affairs at Nokia, said, “all you can do is ask, and if they say no, we believe it.”Tantalum capacitor makers place their faith on their suppliers, who in turn say they have little idea where the minerals originate. Dick Rosen, CEO of AVX, a tantalum capacitor maker in South Carolina, said, “we don’t have an idea where the metal comes from. There’s no way to tell. I don’t know how to control it.”In midst of all this, the United Nations recently issued a report proposing an all-out trade embargo on the import and export of coltan from or to Burundi, Rwanda and Uganda until the countries’ involvement in the exploitation of natural resources from the DRC is made explicit to the Security Council. The numerous practical reasons that arise from policing international trade, especially international trade so critical for multinational technology companies, causes many to believe that enforcement is practically not feasible. As demand is not going to recede for any time soon, the United Nations, as well as its member states, should search for new avenues and outlets in which they can feasibly make this issue more prominent in the international community.Photo by Jon Gosier

By Andrew KimStaff WriterToday’s smartphones are touted to have some of the fastest microprocessors and brightest displays screens capable of functions previously restricted to huge desktop computers, and yet they come at a cost of just a few hundred dollars at retail price. However, a look into the high-tech industry—and more specifically, the industry that assembles the components behind such gadgets—reveals a myriad of hidden costs that often surmount from exploitation and violence.Tantalum is considered one of the most critical components in modern day high-tech gadgets, used in everything from Nokia phones to Sony stereos and Samsung computers. In fact, the mineral has become so critical that it has been referred to as “magic dust.” Tantalum is a power that is made by refining coltan, which currently sells for $100 per pound. The market for tantalum is huge, as roughly 6.6 million pounds of tantalum are used around the world, with “60 percent finding its way into the electronics industry.” The United States is also the world’s largest consumer of tantalum, accounting for around 40 percent of global demand.What is alarming about tantalum is that is that the vast majority of it stems from Africa, with over 50 percent of tantalum coming from the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC). The rush for coltan and tantalum brought in an estimated $20 million a month to rebel groups and militia operating from northeastern DRC. Peasants perform most of the coltan mining in the DRC, with an estimated 30 percent of schoolchildren in northeastern DRC having abandoned their studies in pursuit of mining coltan.From the perspective of the consumer, it is hard to press tech-related companies to use tantalum that has been processed and mined in an environmentally and ethically friendly manner. Before the coltan reaches large regional traders, multiple intermediaries, sometimes up to six, can be involved. Due to this, firms and companies have difficulty in determining if the intermediaries are rebel forces or militia groups. Outi Mikkonen, Communications Manager for Environmental Affairs at Nokia, said, “all you can do is ask, and if they say no, we believe it.”Tantalum capacitor makers place their faith on their suppliers, who in turn say they have little idea where the minerals originate. Dick Rosen, CEO of AVX, a tantalum capacitor maker in South Carolina, said, “we don’t have an idea where the metal comes from. There’s no way to tell. I don’t know how to control it.”In midst of all this, the United Nations recently issued a report proposing an all-out trade embargo on the import and export of coltan from or to Burundi, Rwanda and Uganda until the countries’ involvement in the exploitation of natural resources from the DRC is made explicit to the Security Council. The numerous practical reasons that arise from policing international trade, especially international trade so critical for multinational technology companies, causes many to believe that enforcement is practically not feasible. As demand is not going to recede for any time soon, the United Nations, as well as its member states, should search for new avenues and outlets in which they can feasibly make this issue more prominent in the international community.Photo by Jon Gosier