THE CASE FOR EDUCATION REFORM IN SOUTHEAST ASIA

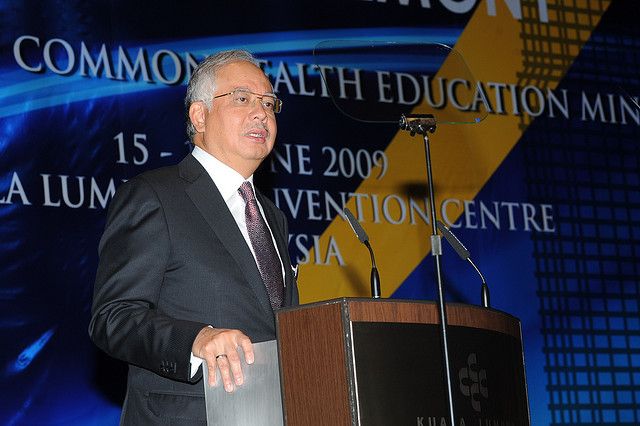

By Kristopher KleinStaff WriterIn the new, global economy the playing field between traditionally developed and developing economies is leveling out. This is apparent with development strategies currently being designed and implemented across Southeast Asia. As Asia begins to pull an increasingly large share of the global economy its way, the nations of Southeast Asia have begun to prepare themselves for a new era of commercial and technological competition. With these reforms, we are witnessing the creation of one of the world’s largest markets and what will potentially be a hub of innovation and commercial growth.Southeast Asia, or more specifically the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), is home to more than 600 million people, has a GDP of 2.1 trillion U.S. dollars and grew at a rate of 5.3 percent in 2013. Beginning in 2015, these economies will open themselves to the free flow of goods, services, investment, labor and capital between the member states and in the process become the world’s third most populous common market.How competitive this market will be, however, will depend on its ability to produce an educated workforce ready to supply its burgeoning market with skilled labor. Improving education must be a high priority if Southeast Asia is to fully realize its potential as a global competitor. National governments across ASEAN have increased investment in universities to help build the educational capacity needed to attract jobs in the skilled labor and services areas, but this may not be enough.According to a study by Harvard University Graduate School of Education Professor Emeritus Noel McGinn, national education systems are ill-prepared to anticipate the needs of a supranational market. McGinn goes on to suggest that “a more helpful alternative is to re-design education to contribute to integration at a trans-national level.” Economic integration gives rise to much larger supranational organizations with an appetite for knowledge very different from their local and national counterparts. If ASEAN is serious about competing in the skilled labor market, it must integrate its education system at a supranational level. Supranational education has been successfully implemented across other common markets like the European Union, where supranational programs have given students opportunities to gain educational and work experience in any of the union’s member states. The freedom to receive an education anywhere across the entire economic community will allow the dispersion of education and educated people to more closely match the demands of the economic community. This seems to fit the stated aims of ASEAN integration in increasing investment in high skill and high technology sectors.On May 22, Malaysian Prime Minister Datuk Seri Najib Razak delivered the keynote address at the International Conference on the Future of Asia. In his remarks, Prime Minister Najib stressed the need to “win support for agreements that can unlock growth and create higher paying jobs,” perhaps referring to on-going negotiations of international trade agreements like the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) involving markets like Japan and the United States. Prime Minister Najib’s statements highlight the need to improve education in order to attract jobs and investment in Southeast Asia. As Southeast Asia becomes increasingly connected to the rest of the world, it will have to create a class of highly educated professionals to compete with foreign workers in high-end sectors. According to an Economist Intelligence Report on ASEAN exports, jobs producing high-vale exports are likely to be better paid, better skilled, less physically demanding and more technologically advanced than those producing low-value exports. It is therefore imperative that Southeast Asian invests in higher education if it is to successfully scale the value chain.Between now and 2017, information technology services in ASEAN will be worth more than $74 billion. Investors increasingly view Southeast Asia as an attractive destination for investment in information technology and in 2014, 14 ASEAN cities were on the top 100 outsourcing destinations. Meeting the growing international demand for information services in Southeast Asia means meeting the demand for human resources.As Southeast Asia realizes it growth potential, it will also be faced with greater economic inequality. Prime Minister Najib, at the Future of Asia Conference, also commented on growing economic disparity saying that inequality following economic growth threatens stability and undermines social progress. "When soaring GDP outstrips living standards, people feel they do not have a stake in their nation’s economic success. That in turn undermines social progress and threatens stability," he said. However, investment in education may slow the growing inequality. Prime Minister Najib stressed the role of government in investing in public goods such as quality education in order to narrow the divide in educational results between urban and rural areas. Furthermore, public support will be needed for promoting social mobility and helping to close the gap between rich and poor.The Association of Southeast Asian Nations and its future common market clearly have very high potential for growth, specifically growth in the high-skill, high-value sectors. However, if ASEAN is to fulfill its potential and become a center for innovation and commercial activity, a serious conversation must be had about reforming and integrating its education system. Investment and reform for education will attract investment and help slow the growth of inequality. If that does not occur, however, the economic development of one of the world’s largest markets will hang in the balance.Image by Commonwealth Secretariat

By Kristopher KleinStaff WriterIn the new, global economy the playing field between traditionally developed and developing economies is leveling out. This is apparent with development strategies currently being designed and implemented across Southeast Asia. As Asia begins to pull an increasingly large share of the global economy its way, the nations of Southeast Asia have begun to prepare themselves for a new era of commercial and technological competition. With these reforms, we are witnessing the creation of one of the world’s largest markets and what will potentially be a hub of innovation and commercial growth.Southeast Asia, or more specifically the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), is home to more than 600 million people, has a GDP of 2.1 trillion U.S. dollars and grew at a rate of 5.3 percent in 2013. Beginning in 2015, these economies will open themselves to the free flow of goods, services, investment, labor and capital between the member states and in the process become the world’s third most populous common market.How competitive this market will be, however, will depend on its ability to produce an educated workforce ready to supply its burgeoning market with skilled labor. Improving education must be a high priority if Southeast Asia is to fully realize its potential as a global competitor. National governments across ASEAN have increased investment in universities to help build the educational capacity needed to attract jobs in the skilled labor and services areas, but this may not be enough.According to a study by Harvard University Graduate School of Education Professor Emeritus Noel McGinn, national education systems are ill-prepared to anticipate the needs of a supranational market. McGinn goes on to suggest that “a more helpful alternative is to re-design education to contribute to integration at a trans-national level.” Economic integration gives rise to much larger supranational organizations with an appetite for knowledge very different from their local and national counterparts. If ASEAN is serious about competing in the skilled labor market, it must integrate its education system at a supranational level. Supranational education has been successfully implemented across other common markets like the European Union, where supranational programs have given students opportunities to gain educational and work experience in any of the union’s member states. The freedom to receive an education anywhere across the entire economic community will allow the dispersion of education and educated people to more closely match the demands of the economic community. This seems to fit the stated aims of ASEAN integration in increasing investment in high skill and high technology sectors.On May 22, Malaysian Prime Minister Datuk Seri Najib Razak delivered the keynote address at the International Conference on the Future of Asia. In his remarks, Prime Minister Najib stressed the need to “win support for agreements that can unlock growth and create higher paying jobs,” perhaps referring to on-going negotiations of international trade agreements like the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) involving markets like Japan and the United States. Prime Minister Najib’s statements highlight the need to improve education in order to attract jobs and investment in Southeast Asia. As Southeast Asia becomes increasingly connected to the rest of the world, it will have to create a class of highly educated professionals to compete with foreign workers in high-end sectors. According to an Economist Intelligence Report on ASEAN exports, jobs producing high-vale exports are likely to be better paid, better skilled, less physically demanding and more technologically advanced than those producing low-value exports. It is therefore imperative that Southeast Asian invests in higher education if it is to successfully scale the value chain.Between now and 2017, information technology services in ASEAN will be worth more than $74 billion. Investors increasingly view Southeast Asia as an attractive destination for investment in information technology and in 2014, 14 ASEAN cities were on the top 100 outsourcing destinations. Meeting the growing international demand for information services in Southeast Asia means meeting the demand for human resources.As Southeast Asia realizes it growth potential, it will also be faced with greater economic inequality. Prime Minister Najib, at the Future of Asia Conference, also commented on growing economic disparity saying that inequality following economic growth threatens stability and undermines social progress. "When soaring GDP outstrips living standards, people feel they do not have a stake in their nation’s economic success. That in turn undermines social progress and threatens stability," he said. However, investment in education may slow the growing inequality. Prime Minister Najib stressed the role of government in investing in public goods such as quality education in order to narrow the divide in educational results between urban and rural areas. Furthermore, public support will be needed for promoting social mobility and helping to close the gap between rich and poor.The Association of Southeast Asian Nations and its future common market clearly have very high potential for growth, specifically growth in the high-skill, high-value sectors. However, if ASEAN is to fulfill its potential and become a center for innovation and commercial activity, a serious conversation must be had about reforming and integrating its education system. Investment and reform for education will attract investment and help slow the growth of inequality. If that does not occur, however, the economic development of one of the world’s largest markets will hang in the balance.Image by Commonwealth Secretariat