It's Not All In Your Head: How Mental Illness Manifests Across Cultures

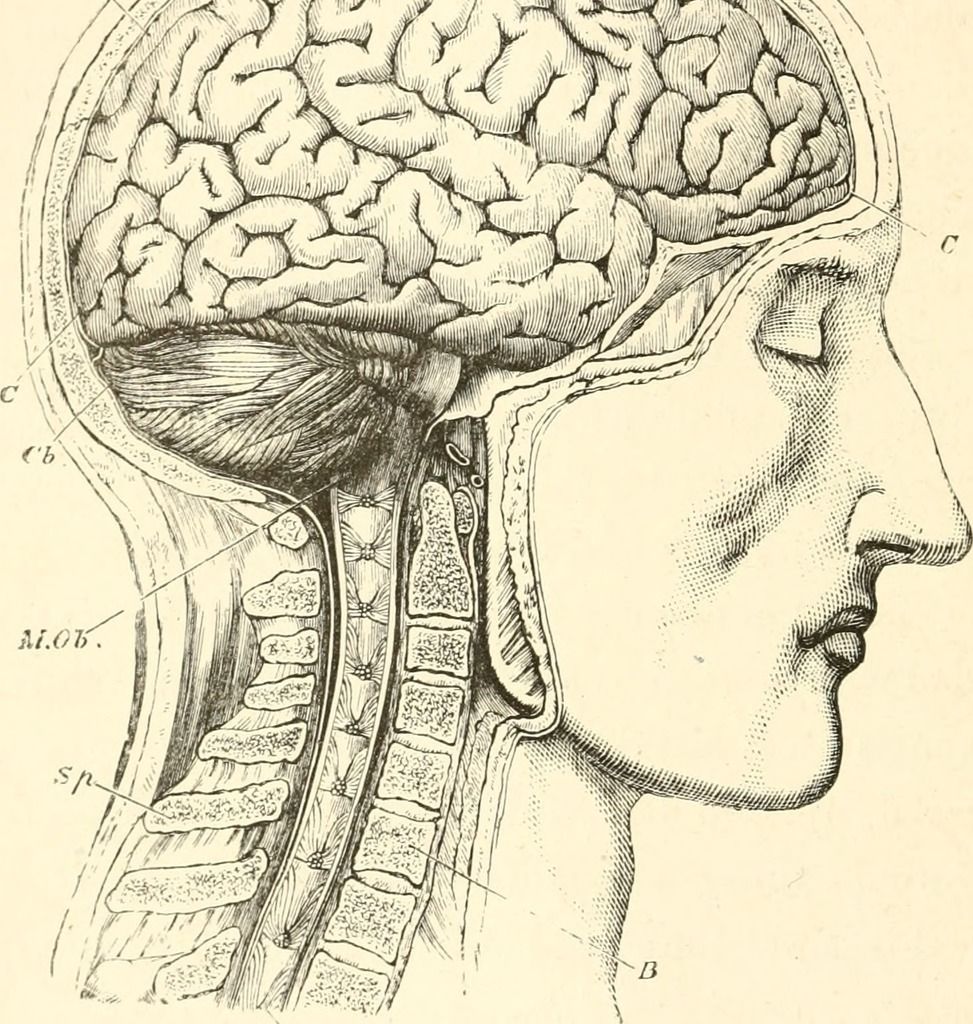

by Becca ChongStaff WriterDepression affects 350 million people worldwide, It is the leading cause of disability, a major contributor to the global disease burden, and one of the most underfunded areas of healthcare in the world. Even in developed countries like the United States, where there is abundant research and resources dedicated to mental health services, the proportion of people who can access them is comparatively small. In the United States, the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders is used to diagnose depressive disorders. There exists an overarching family of disorders, including major depressive disorder, mood dysregulation and even substance-induced depression. The criteria for these disorders are based off of symptoms such as a depressive mood and feelings of hopelessness, reduced interest in daily activities, the inability to sleep, and suicidal ideation. These diagnostic factors are specific to a Western population that has been extensively studied.However, not all cultures and populations in the world experience mental illness in the same way. Many cultures have different “idioms of distress”; that is, they experience somatization in which psychological distress is often presented as physical symptoms of anxiety. The increased understanding of variations for depressive symptoms has shifted popular belief that depression is “an American affliction” to one that affects people on a global scale.Take, for example, how depression presents itself in the Chinese population: as a set of physical symptoms that resemble heart disease and other illnesses rather than a psychological manifestation. Neurasthenia is one such example of how psychological distress leads to physiological symptoms such as fatigue, headache, heart palpitations and even high blood pressure. The reasons for this difference in presentation are thought to be related to the culture-specific values of the Chinese population; the emphasis on interpersonal relations over intrapsychic concerns, the privacy of personal matters, a prevalence of the externalizing coping method, and an emphasis on physical well-being. All this, in addition to the stigma of mental illness, makes admitting to having neurasthenia much easier that admitting to having depression.Structural factors also sanction the somatization of depression through physical symptoms that resemble neurasthenia. The work-disability system and the ability to claim chronic illness allow for a reprieve from the tedium of work in such way that the somatization of mental illness is beneficial. The history of using illness to withdraw oneself from a dangerous situation, such as the political unrest of the Cultural Revolution, is yet another reason that the category of physical disease is much more socially beneficial than claiming a stigmatized mental illness. All this is to say that mental illness diagnoses are culturally-mediated and subconsciously constructed to best suit the environment that the people live in; it is a form of evolutionary survival. Western frameworks of mental illness are not completely compatible with other cultures and have implications for designing mental health care services that will be effective and useful for the people they serve. More research is being done worldwide to learn about these cultural differences that will hopefully bring us to a world where mental illness is treated extensively and competently as a physical diseases.Image by: Internet Archive Book Images

by Becca ChongStaff WriterDepression affects 350 million people worldwide, It is the leading cause of disability, a major contributor to the global disease burden, and one of the most underfunded areas of healthcare in the world. Even in developed countries like the United States, where there is abundant research and resources dedicated to mental health services, the proportion of people who can access them is comparatively small. In the United States, the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders is used to diagnose depressive disorders. There exists an overarching family of disorders, including major depressive disorder, mood dysregulation and even substance-induced depression. The criteria for these disorders are based off of symptoms such as a depressive mood and feelings of hopelessness, reduced interest in daily activities, the inability to sleep, and suicidal ideation. These diagnostic factors are specific to a Western population that has been extensively studied.However, not all cultures and populations in the world experience mental illness in the same way. Many cultures have different “idioms of distress”; that is, they experience somatization in which psychological distress is often presented as physical symptoms of anxiety. The increased understanding of variations for depressive symptoms has shifted popular belief that depression is “an American affliction” to one that affects people on a global scale.Take, for example, how depression presents itself in the Chinese population: as a set of physical symptoms that resemble heart disease and other illnesses rather than a psychological manifestation. Neurasthenia is one such example of how psychological distress leads to physiological symptoms such as fatigue, headache, heart palpitations and even high blood pressure. The reasons for this difference in presentation are thought to be related to the culture-specific values of the Chinese population; the emphasis on interpersonal relations over intrapsychic concerns, the privacy of personal matters, a prevalence of the externalizing coping method, and an emphasis on physical well-being. All this, in addition to the stigma of mental illness, makes admitting to having neurasthenia much easier that admitting to having depression.Structural factors also sanction the somatization of depression through physical symptoms that resemble neurasthenia. The work-disability system and the ability to claim chronic illness allow for a reprieve from the tedium of work in such way that the somatization of mental illness is beneficial. The history of using illness to withdraw oneself from a dangerous situation, such as the political unrest of the Cultural Revolution, is yet another reason that the category of physical disease is much more socially beneficial than claiming a stigmatized mental illness. All this is to say that mental illness diagnoses are culturally-mediated and subconsciously constructed to best suit the environment that the people live in; it is a form of evolutionary survival. Western frameworks of mental illness are not completely compatible with other cultures and have implications for designing mental health care services that will be effective and useful for the people they serve. More research is being done worldwide to learn about these cultural differences that will hopefully bring us to a world where mental illness is treated extensively and competently as a physical diseases.Image by: Internet Archive Book Images