A Shifting EU?: The Rise of the Far-Right in Europe and Upcoming EU Elections

Since the 1980s, the popularity of far-right and populist groups has maintained a relatively steady presence within Europe as the de facto political outsiders of mainstream politics. However, due to both long-held grievances and recent developments, these parties which represent the interests of nationalists, populist nationalists, and ultra-conservatives with neo-fascist roots are experiencing a recent surge of popular support. Their promises of order and control resonate with people’s individual and cultural fears, generating the empowerment of leaders who promise to restrict immigration and, in some cases, democratic freedoms like religion, expression, and the right to protest.

The appeal of these parties has been further exacerbated by the pandemic, the ensuing cost of living crisis, Russia’s war on Ukraine, and the mounting mistrust of mainstream political parties. Far-right leaders have capitalized on this distrust, winning over supporters who feel that their voices and values are not being heard in other political circles. Reaffirming these notions, experts believe that the populist right will see a surge of support in the European Union (EU) parliamentary elections in June of this year, threatening the agenda-setting power that left-leaning political parties typically have in the region.

Even traditionally center or leftist democracies are being overtaken by the influence of right-wing, populist candidates. In the Netherlands, a country often regarded as politically moderate, a rise in economic and political fears regarding immigration has opened doors for far-right parties. One of its small towns, Sint Willebrord, saw approximately 3 out of 4 voters choose the anti-migrant, anti-Muslim party, the Party for Freedom, in last year's election. Anti-migrant policy support follows perceptions of a large influx in the migration of recently displaced peoples.

In Spain, the far-right Vox group recently doubled their national and local vote, outperforming all expectations in regional elections. The rapid and unexpected rise of these parties prompted Spanish Prime Minister Pedro Sánchez to go as far as calling far-right political groups such as Vox the “biggest concern” threatening Western democracies. Also excelling in elections are the Sweden Democrats, a firmly anti-immigration and anti-multiculturalism party. Once shunned from Sweden’s political scene for its far-right views, the party is now the second largest in the Swedish parliament; their situation reflects a larger trend across Western European nations.

This shift is not only evident at the national level but looks to be reflected in major regional organizations as well. In June, EU member nations will elect their next parliament for a five-year term, and far-right political parties are predicted to perform strongly. A poll by the European Council on Foreign Relations (ECFR) suggests that the far-right group, Identity & Democracy, could win 40 additional seats for a total of 98, and therefore become the European Parliament’s third-largest group. Their rise in popularity as a nationalist party reflects many European’s dissatisfaction over the EU’s mismanagement of the refugee crisis.

Moreover, mainstream politicians have inadvertently normalized far-right groups by using their slogans and stances to gain supporters, only further popularizing their adversaries. In addition, far-right parties themselves are adopting more centrist stances on largely popular topics like the EU, changing their position from seeking to leave the union, to a less extreme position of calling to reform it to draw in more centrist voters. As a result, far-right parties are left in a favorable position to garner more support than ever before.

Numerous protests across the continent have popped up as a response to the shift in political power. Austria in particular has seen mass protests with thousands in attendance opposing right-wing parties. A broad coalition of groups such as non-governmental organizations, church communities, and trade unions vocalize their displeasure over the rise in right-wing extremism, antisemitism, and racism in their communities and nation at large. Under slogans such as “defend democracy,” protestors have demonstrated tirelessly in front of the Vienna parliament building.

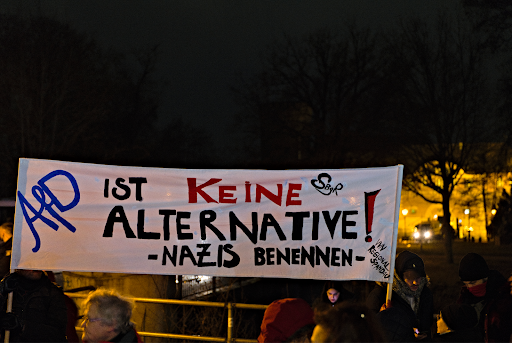

"Protest against AfD event at Zitadelle Spandau 2023-02-03 11"

by Leonhard Lenz is marked with CC0 1.0.

Protests extended into Germany as well, after reports of a secret meeting being held by right-wing extremists, including Germany’s far-right party the AfD. The party, often appearing in headlines as that of neo-nazis, discussed the mass deportation of both foreigners and German citizens of foreign origin in the meeting. While mass deportation policies are no secret agenda of the far-right, growing crowds of protestors signal a rise in popular opposition to the AfD in a way that has not been seen before. Though AfD won several key local elections last year, being the first far-right party to do so since the Nazi era, the backlash against their rise has evolved into a greater movement. What once were small gatherings against them are growing large, and, in many cases, larger than what protest organizers expected.

A fundamental shift in Western European political values is increasingly apparent, and EU Parliament elections in June could very much reflect that. While mainstream politicians were always aware of growing far-right support in past election cycles, this time around, the groups once known as political outsiders now have a plausible opportunity to influence Europe’s policy agenda. Positions on important issues range from an increase in pro-Russia support, a decline in protective climate laws, and harsher crackdowns on immigration. Given these facts, the eyes of the world will surely turn to the EU in June in observance of what is likely to be an extremely noteworthy Parliamentary election.